The Reuter Organ Company Centennial

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Reuter Organ Company.

Since its founding in 1917, they have successfully designed and built

more than 2,240 instruments for churches, concert halls, and residences.

The Reuter Organ Company officially began operations on April 17, 1917. At that time, Adolph C. Reuter had worked in the organ industry for over 15 years and held supervisory positions at Wicks, Casavant, and Pilcher. He had been meeting with area businessmen since the beginning of the year to organize his own company. Before the end of the year, the new firm had installed its first organ at Trinity Episcopal Church in Matoon, Illinois. This organ still plays weekly services and will be featured in a recital this November—100 years and one day after it was first used on a Sunday morning.

Our last anniversary article in The American Organist (March 1992) gave a detailed history of the first 75 years of the company. For this issue, we decided to focus our attention on the last 25 years. Thus, the cover features our organ at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Springfield, Illinois, completed this past year, framed by photos of other instruments that we have installed over the last two decades. A biographical essay by JR Neutel, Reuter president, precedes the description of the Cathedral organ.

We invite you to visit the Reuter Organ Company website for additional information on our company and its history.

–Ronald Krebs, Vice President

From the President

My time with Reuter began in January 1980, just before my father, Albert Neutel, and Franklin Mitchell assumed control of the company. I spent the next six years working in the various aspects of organ building throughout the shop.

In 1986, I moved to Memphis to become a sales and service representative for the firm. At the same time, I was also asked to assist Franklin Mitchell with tonal finishing of an organ we had installed in Milwaukee. My experience with Franklin continued as we worked on many other instruments over the next eight years and I learned the art of voicing. Franklin was a consummate organist and we spent many hours talking about organ design and voicing. A day of voicing typically ended with him auditioning what had been accomplished and revealing the subtle nuances of color and blending he sought out in the voicing process as he played.

My time with Franklin taught me how to truly listen. For me, however, the art of listening was not limited to the sound of pipes. The more time I spent in the field in those early years, the more important it became to me to ask organists and choral directors what they expected of a pipe organ—right down to a stop-by-stop analysis. These musicians continue to share their knowledge and experiences with me and offer valuable insight that continues to guide our work as stylistic approaches evolve and technology advances.

In 1997, I returned to Lawrence to work alongside my father and learn more about running the business. At that time, my duties also included heading the Reuter tonal department, and we decided to retire the concept of the “tonal director.” For too long, and in too many firms, the director was also viewed as a dictator. I wanted our company to listen to, and be challenged by, our clients.

While Franklin was the artistic side of the organbuilding, my father was the businessman. His business acumen ensured that we would ultimately achieve this landmark year. My father was also a master at bringing out the best in folks. Under his guidance, the team was assembled that now leads the firm into the future from a modern, spacious facility. Today, he is enjoying his retirement in Florida.

Many of my conversations begin with “what do you think of this idea,” or “can we do this.” All our employees know that thinking outside the box often can lead to good things. When it comes to tonal concepts, our motto is the road is wide, but, if wrong, the tonal abyss is deep! This philosophy has resulted in the signing of many contracts.

While this narrative shares some insight into what I want Reuter to be, I want to commend and thank management and all the craftspeople—the organ architects/designers, the folks building the consoles, those who pour the metal and make the pipes, the chest builders, those who apply lacquer, the folks who assemble all the components—who have shared their talents in making Reuter what it is today. Each day for 100 years, the willingness and commitment to excellence by our employees has set our company apart.

I also want to thank all our clients. Every day brings a fresh adventure and the ability to learn something new. There are new places to see and new acquaintances to be made. It is an honor to work with you to the successful completion of each project. Dedicated to artistry and integrity, we remain at your service.

–JR Neutel

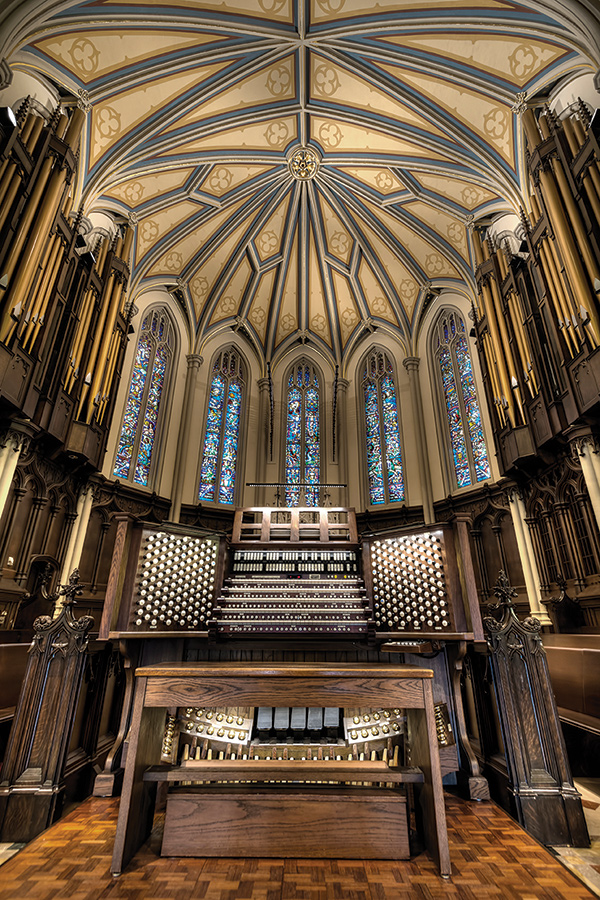

The Cathedral Organ

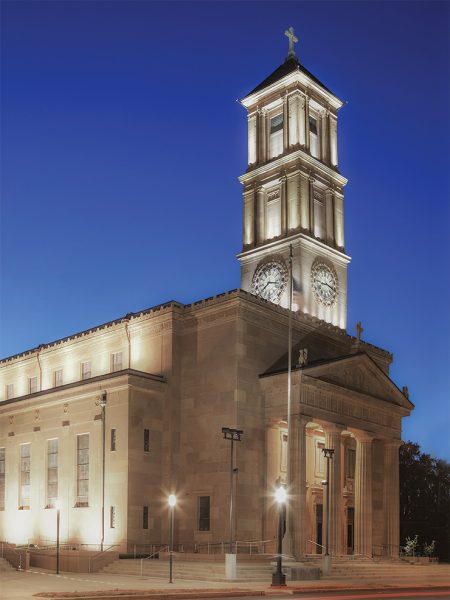

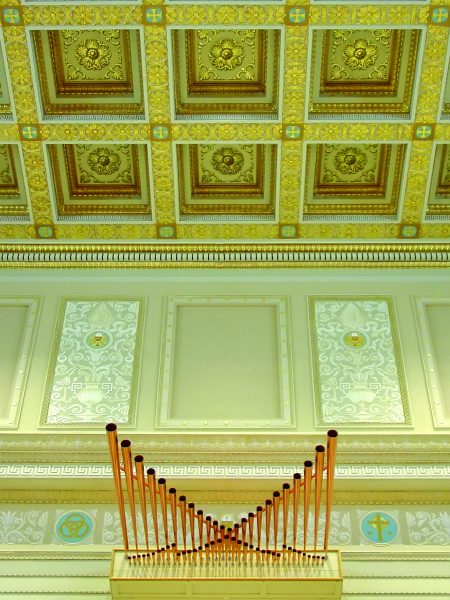

The story of the new organ at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Springfield, Illinois, is like that of the building, one of renewal to much better than new. The building, dedicated in 1928 and featuring an interior fashioned after Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, was meticulously restored in 2009.

The core of the gallery organ began its service in 1971 as Reuter Organ Company’s Opus 1763, a three-manual, 43-rank instrument built for the Broadmoor Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi. The Broadmoor congregation has since moved on to both new quarters and worship style. During a hot summer week in 2015, the organ was removed and loaded onto two trucks to make its way back to Lawrence for comprehensive renewal.

The Broadmoor organ reflected the tonal priorities of an earlier time, with limited 8’´tone and an abundance of upperwork. As we now prefer a tonal design built upon strong foundational tone, several modifications were done to prepare the organ for its new purpose at the cathedral. As is customary in rebuilding organs of this period, a new Great chorus anchors the ensemble, with the existing choruses being redeployed and refurbished for secondary roles. Colorful solo sounds were added, including the restoration of four stops from the cathedral’s 1928 Wicks organ. A commanding new Trompette en Chamade completes the gallery organ.

In addition, a small Antiphonal organ was renovated and installed above the high altar. It is based on another vintage organ, Reuter Opus 703. Originally built in 1946 for a Methodist church in Greensburg, Kansas, Opus 703 later served Trinity Lutheran Church in Beatrice, Nebraska, from 1963 until 2014, when it was briefly used as a residence organ. This truly ecumenical instrument can be played from its own console or from the gallery.

The acoustic of this elegant building tends to favor low and midrange frequencies over the upper ranges. The strong treble qualities of the earlier instrument offer the ensemble a clarity and definition, while allowing the organ full advantage of the space’s qualities. The bass travels gently down the nave, while the 8’´foundations build energy and bloom in the warm ambience. The finished instrument easily fills the grand space and effortlessly leads a large congregation in song. There are abundant tonal resources for convincing performances of the organ literature. Just as important, it offers many opportunities for choral accompaniment, with complete, supportive choruses in each division.

The cathedral’s visual grandeur with its sympathetic acoustic makes for a most uplifting setting. We are honored to have been chosen for this important project, and we can all look forward to generations of inspired worship and music.

–William Klimas, Artistic Director

From the Cathedral Staff

It was late summer in 2015 when I was asked to serve on a committee for the purpose of renovating or replacing the cathedral pipe organ. My “yes” was instant. Our committee of four quickly decided to replace the old pipe organ. Knowing we had a specific budget to work with, the search was on for a vintage instrument that would meet our worship needs and become a focal point for sacred music of all kinds for the Cathedral community.

I’m delighted to say that the Reuter Organ Company was able to offer us a wonderful used instrument that needed a new home. Ultimately, JR Neutel and his staff installed an instrument that is nearly twice as big as the organ that was replaced and offers a much broader tonal spectrum than was ever available before. The instrument is a tremendous success.

–Mark Gifford, Interim Organist and Director of Music

In 2009, our Cathedral underwent a large-scale restoration. The project was a great success, but lacking in one area: the organ. I am so very happy that the Reuter Organ Company was able to finally supply the “missing piece” in the Cathedral. The instrument, and the service that has gone with it, has met and exceeded all of our expectations. The beauty of the Cathedral church and our liturgies is only enhanced by this great work of the Reuter Organ Company.

–Reverend Christopher A. House, Pastor, Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

Hear this organ: