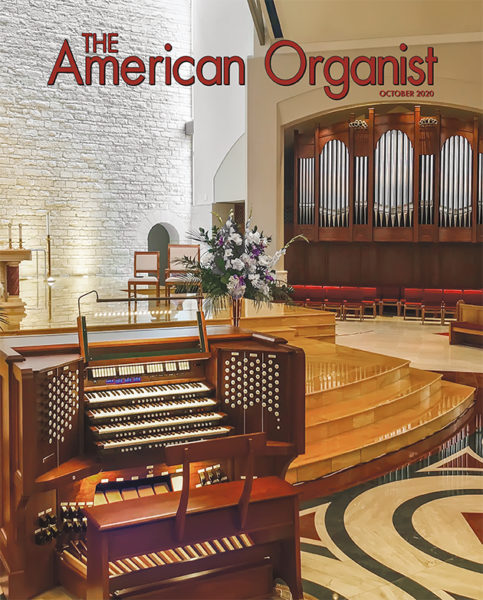

St. Andrew the Apostle Catholic Church

Clifton, Virginia

Peragallo Organ Company

Paterson, New Jersey

Stop List

By John Peragallo III

Today, we inescapably find ourselves in a world of ecclesiastical change, with many venerable parishes being forced to close their doors. Fine organs that provided years of liturgical service for generations of worship are becoming available as one of the more valuable assets to be disposed of. The decision to pursue a repurposed instrument or utilize pipes from one of these vintage organs is a real choice. The possibility of ending up with a bit of history is coupled with the overall cost savings compared with a completely new instrument. Properly relocated and reimaged, these organs can find new life as the cornerstone of yet another successful music ministry. This is the story of one such happy marriage!

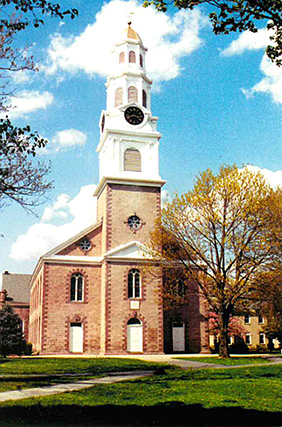

The new instrument at St. Andrew the Apostle Catholic Church began life many years ago, several states north of Virginia. In 2008, the historic Bloomfield Presbyterian Church on the green in Bloomfield, New Jersey, commissioned Peragallo with the building of a new organ under the guidance of Timothy Tarantino, who was then organist of the parish. This new instrument was to contain pipework from previous instruments, including the two-manual, 33-rank L.C. Harrison & Co. organ installed in 1883 and presided over by none other than Charles Ives during his time in New Jersey. This was followed by the 1911 Austin Opus 347, a three-manual, 30-rank organ updated in 1958–59, with subsequent relocations and new pipework by the Church Organ Company in 1970. Quite a historical legacy!

The 2008 Peragallo Opus 693 was a French Romantic design of 2,881 pipes across the rear of the choir loft in chambers fronted by gorgeous pipe cases and a handcrafted, cantilevered Great casework of solid mahogany. New pipework stood alongside the vintage repurposed pipes of these various builders. When the church was closed, merely months after the organ dedication date, we were heartbroken. The congregation had spent years and large sums of money to study and stabilize the structure, only to be left with a historic space that needed extensive and costly restorations. They approached us knowing that one of the most valuable assets they possessed to get back on their feet was this new organ, and asked us to explore finding a new home for it.

Enter Mike Murphy, organ committee chair at St. Andrew’s, in search of an instrument to serve as the cornerstone of his vibrant parish music ministry in Clifton, Virginia. The Peragallo family subsequently visited the church to evaluate the worship space and discuss the role of the organ in parish worship. We immediately recognized that we had found a perfect solution for both churches.

The worship space of St. Andrew’s is far from the traditional architectural style of the classically American Presbyterian church in Bloomfield. The new space for the instrument is formed by many angled surfaces and is entered via the center of one of the long sides, with the altar and tabernacle on the opposite wall. A chapel area shares the acoustics of the sanctuary, and a majority of the room is circled by a balcony that is home to the music ministry.

Several factors made this an exceptionally inviting match: the general size of the instrument (51 ranks), the like-new condition (a 2008 completion not played since 2009), the low-profile terraced key desk (Mike Murphy is very fond of French organ literature), the scaling of the pipework (the acoustic and volume of the spaces are similar), and finally, our vision to reconfigure the existing casework within the new worship space.

The parish of St. Andrew the Apostle is most collegial, and all aspects of ministry, both old and young, were soon involved with fundraising efforts for the new instrument. Associate vicar Fr. Brigada set up a “Pennies for Pipes” drive in the school. Several evenings were held at parishioners’ homes to educate all on the positive effect a fine pipe organ can bring to a growing music program. A Sunday afternoon celebration at the local Paradise Springs Winery allowed us to unveil the reimaged organ design for the choir and interested donors. The Diocese of Arlington signed a contract with Peragallo in August 2019, launching the process of reconfiguring the organ for its new parish.

The new design consists of three independent handcrafted cases of mahogany. Each division is tonally very complete within itself. The pipes of the Grand-Orgue are positioned high in the center case, allowing the sound to follow the roofline and flood the nave with balanced tone. The larger pedal flues are in a new addition to the rear of the Grand-Orgue case. The expressive divisions are set in complementary cases, with the tonal openings positioned at an angle firing across the nave. Instead of sounding like three independent entities, this configuration creates tonal blend. Finally, these three cases set up a most welcome acoustical shell to gather and enhance tonal projection of choral music into the nave.

As with most Peragallo installations, one expects to find a chamade—whether a chorus reed or a decorated commander in chief! The solo reed is mounted in a clustered design and is indeed a true leader on high wind pressure. The resonators are large-scale, with big flares and Willis shallots. The tone is rounder than the complementing French Bombarde of the Choeur division.

Worthy of special mention is the uniquely designed Chapel/Cantor Chancel Organ. This division speaks from an alcove on the far end of the sanctuary, allowing the Walker digital voices to speak nicely into both the chapel and the sanctuary. The stop selection of this organ is purely functional—to accompany the cantor in the sanctuary without the congregation hearing the organ first. Rather than placing the stops all on one floating division, we have considered the implementation of the sounds in worship. The Chancel Récit features two gorgeous solo stops—the Corno di Bassetto, and the Flauto veneziano to intone the psalm refrain. The Chancel Choeur includes a two-rank Cor de chamois céleste to accompany the psalm verses. Finally, the Chancel Grand-Orgue is home to a small principal chorus to provide congregational accompaniment in the chapel.

The integration of the organ in the new space was a truly collaborative experience. Parishioners Mike Murphy and Mike Hadro brought unrelenting energy to assure that this project would become a reality. We thank recently installed pastor Fr. Robert Wagner and Diocese of Arlington representative Mike Thorton for their patience during all the challenges brought with the installation of this organ during the coronavirus pandemic.

It is our sincere hope that Opus 693/762 will provide a firm foundation for the musical faith life of this wonderful parish for many years to come.

John Peragallo III is president of Peragallo Organ Company. Website

Photography: Clarence Butts