By Roy L. Belfield Jr.

Note: This article originally appeared in the December 2014 issue of The American Organist

For 42 years, Carl G. Harris Jr. was the consummate choral conductor. His versatility as a musician too was masterful, and a matter of record. I met Harris in 1979, when he was a professor of music and choral director at Virginia State College (now University) in Petersburg, Virginia. A skilled organist, he was my first organ teacher, from 1980 to 1985. He became my mentor and longtime friend. Our close relationship afforded me an exclusive opportunity to reflect with him on his extensive career as choral conductor, music educator, organist, pianist, accompanist, lecturer, and church musician. Throughout his 57 years of teaching, Harris strove for perfection and achieved excellence. I interviewed him in summer 2012, before he passed away on June 23, 2013. It has been my honor and privilege to learn more about Carl Harris—a trailblazer, choral music pioneer, and musical historian

Harris was born on January 14, 1935, in Fayette, Missouri. He attended public schools in St. Joseph and graduated with honors from Bartlett High School in 1952. He earned a bachelor of arts degree in music from Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1956; a master of music degree in music history from the University of Missouri–Columbia in 1964; and a doctor of musical arts degree in choral conducting from the University of Missouri- Kansas City Conservatory of Music in 1972. Harris was the first African American to receive the doctorate in music from the Conservatory of Music. His choral conducting teachers included Thomas Mills, Ferdinand Grossman, Jay Decker, Gunther Theuring, and W. Everett Hendricks.

As a choral director, Harris taught at the following high schools and colleges: Walker High School, Magnolia, Arkansas (1956–59); Philander Smith College, Little Rock, Arkansas (1959–68); Hickman High School, Columbia, Missouri (1963–64, while completing his master’s degree); Johnson County Community College, Overland Park, Kansas (1969–71); Virginia State University, Petersburg, Virginia (1971–84); and Norfolk State University, Norfolk, Virginia (1984–97). Harris also served as chair of the music departments at Virginia State University (1977–84) and Norfolk State University (1984–97). From 1998 to 2013, he was on the faculty at Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia, where he taught music history, advanced conducting, piano, organ, and accompanied the Hampton University Choirs as well as departmental recitals. From November 2011 until May 2012, he was interim director of the Hampton University Choirs, following the untimely demise of his mentee and colleague Royzell Dillard (1961–2011), director of the Hampton University Choirs from 1988 to 2011. As an active and gifted choirmaster and organist, Harris served four churches, all of which are known for their rich traditions of music: Wesley United Methodist Church, Little Rock, Arkansas (1960–63); Centennial United Methodist Church, Kansas City, Missouri (1968–71); Gillfield Baptist Church, Petersburg, Virginia (1974–85); and Bank Street Memorial Baptist Church, Norfolk, Virginia (1985–2005). Until his death, Harris continued to serve as a substitute choral director and organist in the Hampton Roads region of Virginia.

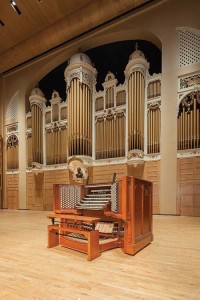

At the time of our interview, I knew very little about Harris’s earliest musical training, so I asked him to share some of his musical experiences from childhood and as a young adult. He remembered playing hymns from Gospel Pearls and improvising during worship services at his home church, First Baptist Mount Union in St. Joseph, Missouri. Also, he recounted accompanying the St. Joseph Gospel Chorus, under the direction of Ernest Hawkins. During this time, Harris also studied piano and organ with Elsie Barnes Durham at First Baptist Church, also in St. Joseph. It was there that he took his first organ lessons on a 45-rank Austin. While at Bartlett High School from 1948 to 1952, he played trumpet in the band and accompanied the school choir. Harris enjoyed remembering his days as accompanist for the Philander Smith College Choir and performing in the band and jazz ensemble. The choir, which performed mostly in Methodist churches at that time, toured the Midwest and East Coast to recruit students and raise money for the college. Each year, the choir made a recording that was played over a nationally broadcast college-choir series sponsored by the United Negro College Fund.

Harris’s first teaching position was at Walker High School. This was also his initial experience as a choral director. Under his direction, the choir performed for community events and school functions, and received superior ratings for three consecutive years at the Philander Smith music festival. During that time, black schools were not permitted to attend state-sponsored music festivals. After desegregation in Arkansas, Harris was invited to adjudicate choirs in both regional and state festivals.

* * *

I asked Harris how he chose choral conducting as a career. He replied that it chose him. At Philander Smith, he was a piano major. After receiving his BA degree, he went to Magnolia, Arkansas, to teach English and music, which included the high-school choir. After three years, he was asked to return to Philander Smith, to conduct the summer commencement choir–and he stayed for nine years. Harris warmheartedly remembered his earliest mentors and how they influenced him. He noted that Elsie Barnes Durham, his piano and first organ teacher in St. Joseph, Missouri, was his first mentor. She nurtured him in piano and organ studies and also in music theory, music history, and basic musicianship. Stanley Tate and Otis D. Simmons, who were choir directors at Philander Smith, introduced him to the great hymns and anthems of the church at chapel and vesper services on campus, where they faithfully used the 1935 Methodist Hymnal. Tate and Simmons also instilled in him a love and appreciation for African-American spirituals through choral arrangements by Ruth Gillum (1906–91), another Philander Smith choir director. Harris’s other mentors included Thomas Mills, choral conductor at the University of Missouri- Columbia, and W. Everett Hendricks, conductor of the Heritage Singers at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music. These two choral legends introduced Harris to choral masterworks and carefully guided him through the stylistic preparation and performance of each work.

* * *

Harris spoke often of his close friendship with renowned composer Undine Smith Moore (1904–89). His insightful memories and stories of Moore were greatly detailed with a cherished perspective into her life as a teacher, composer, and friend. He affectionately recalled how Moore was on the faculty at Virginia State College when F. Nathaniel Gatlin (1913–89), then-music department chair, invited him to join the faculty as choral director in January 1971. Harris had conducted Moore’s “Daniel, Daniel, Servant of the Lord” and “Striving after God” with the Philander Smith College Choir. Also, he performed the first work as assistant conductor of the Heritage Singers at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. Eventually, Moore and Harris developed a mutual admiration and respect for each other. Together, they worshiped at Gillfield Baptist Church, where she was a faithful member and the organist. Harris and Moore often enjoyed brunch together after Sunday services at Gillfield. They discussed her choral music, African-American spirituals, texts for sacred and secular choral works, larger extended works, and performances of many genres of music, but mostly choral performances.

Harris conducted many of Moore’s arrangements and compositions with the Virginia State College Choir. Frequently, they were privileged to rehearse and perform these works before final manuscripts were sent to a publisher. When Harris arrived at Virginia State, Moore was finishing her anthem “Lord, We Give Thanks to Thee,” which was composed for the centennial celebration of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Harris also stated that in 1974, Moore composed a setting of Donald Hayes’s poem “Benediction,” which was dedicated to him and the Virginia State College Choir. Although it was never verbalized or suggested by Moore, this unpublished favorite of Harris’s was written in grateful appreciation for the 1974 recording of the Undine Smith Moore Song Book by the Virginia State College Choir. In 1980, Harris was honored to play a part in the Virginia premiere performance of Moore’s largest opus, Scenes from the Life of a Martyr, a cantata based on the life, work, and death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. For this premiere,the choirs from Virginia State, Norfolk State, Hampton Institute (now University), and other Virginia colleges joined forces with members of the Richmond Symphony Orchestra; however, the unofficial first performance of Moore’s masterwork took place in 1979 at Gillfield Baptist Church. The Harry Savage Chorale,under the direction of Savage (1912–92), was accompanied by the composer at the piano using her unpublished manuscript.

Carl Harris lectured frequently on the life and works of Undine Smith Moore and, specifically, what influenced her choral music. He stated that Moore was born in Jarratt, also known as Southside Virginia. Her music was greatly inspired by family members who sang spirituals and work songs in the kitchen, field, and garden. She thought this music was beautiful, yet different. Moore entered Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1922 and never forgot those unique melodies she heard as a child. It was at Fisk that she began documenting those unfamiliar tunes heard only in Southside Virginia. While at Fisk, Moore studied theory and composition with prominent teacher and composer John W. Work II (1873–1925). Harris recalled from conversations with Moore that Work encouraged her to notate those tunes she heard while growing up in Virginia. Undoubtedly, she was influenced by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who were known for singing spirituals nationally and internationally. One of her classmates was John W. Work III (1901–67), who was also known for his preservation of African-American folk music.

In 1927, Undine Smith Moore joined the faculty of Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute in Petersburg, where she taught theory, piano and organ, and continued to arrange and compose for the college choir. Harris added that Moore began directing the choir when director J. Harold Montague (1907–50) joined the army. She began composing out of necessity: oftentimes, there was no money to purchase music; so she would write her own choral compositions. Much of her choral music was written for and debuted by the Virginia State University Choirs. Harris added that Moore frequently shared her music with other colleagues who influenced her: R. Nathaniel Dett (1882–1943) of Hampton University and Noah Ryder (1914–64) of Norfolk State College. Harris emphasized that Moore did not try to make the folk melodies better in her compositions, but wanted to notate them as close to what she heard as a child. Her music was certainly sophisticated in form, but sensitive to the essence of authentic folk music. She wished to preserve those melodies her mother and other relatives sang at home and in church. As a verified authority on Moore, Harris recognized her as a brilliant music theorist who used her skillful craft to enhance the pure spiritual melodies she heard as a child in Virginia.

From 1928 to 1931, Moore completed graduate work at Columbia University in New York during the Harlem Renaissance, where she became personally acquainted with poet Langston Hughes. As a result, several of her choral works are based on his writings. Carl Harris knew personally that Moore was an avid reader and also enjoyed the writings of Thomas Blake, Donald Hayes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., and Claude McKay.

Harris finally expressed how Undine Smith Moore’s teaching, composing, and performing were greatly influenced by her colleague and close friend Altona Trent Johns (1904–77), who was an outstanding pianist and music educator in her own right. Harris affirmed that Johns’s musicianship, research, and teaching were equally superior and merited the utmost respect. Johns and Moore worked closely together for 20 years at Virginia State University, where they established the Black Music Center, which brought a series of seminars on black music, art, dance, and drama to campus. The pair also traveled to Africa in 1972 and collected musical ideas that influenced some of Moore’s choral writing. Without a doubt, Harris knew that Moore had the support of Johns, who encouraged and inspired her to preserve the music of her childhood.

* * *

In our conversations, Harris identified other choral conductors, composers, and arrangers who significantly shaped his career and perspectives on choral music. He acknowledged that his essential philosophy of choral music was influenced and represented by two of the foremost American choral schools of thought: the Westminster Choir, founded by John F. Williamson (1887–1964), and the St. Olaf College Choir, founded by F. Melius Christensen (1871–1955). Harris indicated that his choral conducting style was a melding of the performance practices advocated by these choral pioneers, along with the rich choral traditions of the African-American churches and colleges and universities he served, and the countless musical geniuses who also served these institutions.

Harris traveled and performed extensively as a choral conductor. He treasured the annual tours with the choirs of Philander Smith College, Virginia State, Norfolk State, and Hampton universities—which gave him an opportunity to travel throughout the United States and Canada. In summer 1969, Harris traveled for six weeks with the Heritage Singers of the University of Missouri–Kansas City Conservatory of Music. They traveled to Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Holland, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, where the singers participated in a choral symposium of music from the classical period. The final concert was a performance of Franz Joseph Haydn’s The Creation, which featured five American university choirs and a symphony orchestra, under the direction of Gunther Theuring. In 1972 and 1973, Harris returned to Europe as a faculty member of the U.S. Army’s Protestant Church Music Workshop in Berchtesgaden, Germany. In 1974, he was selected by the president of the American Choral Directors Association as one of 36 American choral conductors for the American’s People-to-People six-week goodwill tour of Eastern and Western Europe. They toured Austria, England, France, Germany, Poland, and the Soviet Union. Throughout this tour, American conductors worked with their European counterparts. While in France and Germany, Harris conducted spirituals in their native language. While in Paris, he met celebrated composer and teacher Nadia Boulanger; and in London, he met Ursula Vaughan Williams, widow of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Harris also attended conducting masterclasses with Helmuth Rilling in Germany and Marcel Courand in France. During 1976 and 1977, Harris took a sabbatical leave from Virginia State College to serve as music consultant for the Chaplain’s Corps of the U.S. Army in Europe. For six months, he toured several U.S. Army bases in Belgium, Germany, Greece, and Italy. He served as workshop leader for military chapels, and attended concerts, operas, ballets, and recitals in Europe. He also played piano recitals in Germany and Italy, which enhanced his performance practice techniques and musicianship.

I was very interested in some of Harris’s most significant accomplishments during his career as a choral conductor at Philander Smith, Virginia State, and Norfolk State. At all three schools, and Hampton University, Harris had the good fortune to mentor countless students who continue to make beautiful music as teachers, church musicians, and performers. He noted that one of the joys of teaching was the opportunity to engage and collaborate with students pursuing master’s degrees, and supervise theses, terminal projects, and recitals. Ultimately, Harris’s task was to successfully master the art of being an effective choral conductor, music educator/administrator, and church musician, all at the same time.

* * *

Harris was a true and constant advocate of the African-American spiritual. I asked him to detail his thoughts on the evolution of the arranged spiritual. He readily stated that, in addition to Undine Smith Moore, R. Nathaniel Dett, Noah Ryder, and John Work III, it was Edward Boatner (1898–1981), Harry T. Burleigh (1866–1949), and Hall Johnson (1888–1970) who made the spiritual accessible and universal to all choirs with their published arrangements. He added that the early choral music of William Dawson (1899–1990) also helped make this music sound authentic. Harris had the

good fortune to meet and work with Dawson at several American Choral Directors Association conventions, where Dawson shared his perspectives on the arranged spiritual through numerous lectures and presentations. According to Harris, Edward Margetson (1892–1962), Clarence Cameron White (1880–1960), and Ruth Gillum, who were perhaps lesser known, also arranged spirituals. Harris pointed out that so much of this early choral music by black composers and arrangers was published by Handy Brothers Music Company Inc. in New York.

In addition, Harris remembered listening to spirituals as sung by the Wings Over Jordan Choir, under the direction of Glynn Settle. During the 1950s, this choir sang spirituals on a weekly Sunday-morning radio program. There was also a national broadcast on Sunday mornings that featured black college choirs during the 1950s and 1960s. It was this kind of attention that gave the a cappella spiritual arrangement its celebrated appeal. Harris identified early sources on the spiritual: American Negro Songs and Spirituals by John Work III and The Books of American Negro Spirituals: Two Volumes in One, edited by James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938), with arrangements by J. Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954).

In Harris’s opinion, some of the more recent arrangers of the spiritual are moving away from the purity of this music. He further suggested that many contemporary spiritual arrangements are over-arranged: the dialect and rhythm are overly exaggerated, resulting in the loss of spirit of the true spiritual. Harris strongly felt that the language and the rhythm of the spiritual should be natural and worshipful. He proudly stated that choral conductors would certainly find these elements in the numerous published spiritual arrangements by Undine Smith Moore.

* * *

As I reflected with Harris on his vast career, I wondered if there was anything he would do differently. He quickly replied that he thoroughly enjoyed and appreciated the diversity his career gave him for nearly 60 years. Conducting his choirs was a particularly important part of the driving force of an extraordinarily fulfilling life. In his final years of musical creativity and activities, Harris smiled and said he had not missed having a choir to rehearse and conduct, or tour with, on a regular schedule. He admitted that serving as interim director of choirs at Hampton University brought back fond memories of all of the college choirs he had conducted; however, he found joy in accompanying the famed Hampton choirs. His work there also allowed him to teach piano and organ, and serve as university organist, a title and position he so enjoyed.

Harris told me that my interview with him triggered remembrances of all the talented and generous teachers, mentors, and musicians who taught and inspired him over the years. He was truly thankful to God for his students and all others with whom he had been able to share his talents within the classrooms, rehearsal and concert halls, studios, and sanctuaries.

I have admired Carl Harris and his remarkable career for more than 30 years as he combined the areas of teaching, administration, and performance. When I asked if he intentionally varied his professional experiences, he acknowledged it was by choice and perhaps out of financial necessity that he became a music teacher. Becoming a choral conductor, music administrator, performer—and, yes, a church musician—was all the result of having teachers and mentors who encouraged and emboldened him. He also felt it was important to include Georgia Atkins Ryder (1924–2005), widow of Noah Ryder, to his list of mentors. Ryder, who served as dean of the College of Arts and Professions at Norfolk State University, invited Harris in 1984 to join the music faculty as choral director and chair of the music department. In each assignment, Harris was given the chance to prove his competence and preparation— and, in the end, he was immensely grateful for the assurance that God’s amazing grace had been with him along his musical journey. Having taught for more than half a century, he was convinced that his life seemed to come together with time and patience, with each experience falling into place to make the total picture a bit clearer and complete.

Finally, I asked Harris what advice and wisdom he would share with me and other young choral conductors. He strongly urged us all to be true to ourselves and to be champions for quality choral music in our schools, churches, and culture. As an expert and sensitive choral conductor, he understood that one must be a dedicated musician and teacher, a lifelong learner, linguist, psychologist, and historian— and, above all, a friend to the singers in one’s care.

In her 1958 setting of “Striving after God,” Undine Smith Moore utilized Michelangelo’s poignant text, which constantly inspired Carl G. Harris Jr. and captured the complete essence of his life:

True art is made noble and religious by the mind producing it. For those who feel it, nothing makes the soul so religious and pure as the endeavor to create something perfect. For God is perfection, and whosoever strives after perfection, is striving after God.

Roy L. Belfield Jr., a native of Petersburg, Va., earned a bachelor of arts degree in music from Morehouse College in Atlanta, master’s degrees in music education and organ performance from Florida State University in Tallahassee, and the doctor of musical arts degree in organ performance from the University of Missouri–Kansas City Conservatory of Music. He is associate professor of music and director of choral activities at Texas Southern University in Houston.

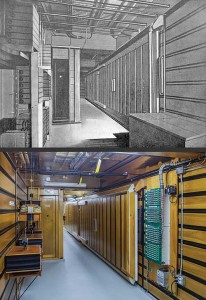

Photo of the Virginia State College Choir courtesy of Virginia State University Libraries, Johnston Memorial Library, Special Collections and University Archives