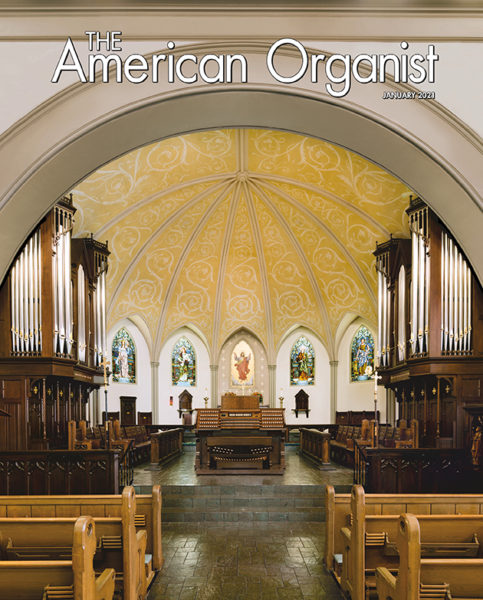

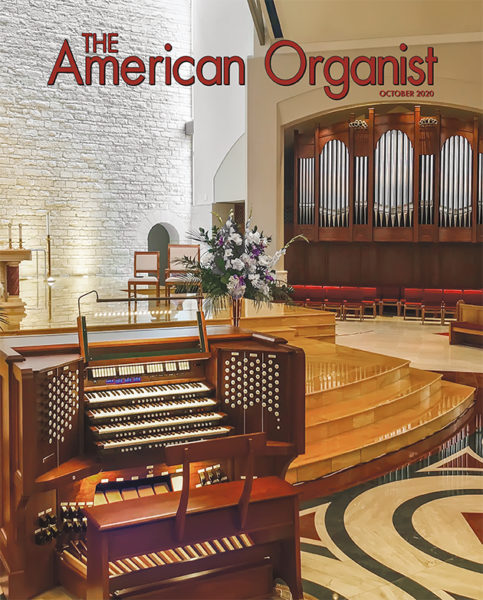

Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church

New York City

Aeolian-Skinner, Opus 908

Restoration by Foley-Baker Inc.

Tolland, Connecticut

Stop List

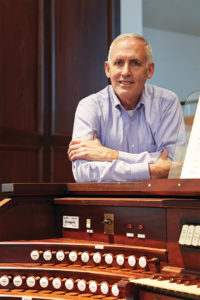

By Mike Foley

In over 50 years in the organ business, I have learned that few organs were as heavily used as those in Catholic churches during the mid-20th century. I recall working in Waterbury, Connecticut, in the mid-1970s, releathering the organ at just such a church, where there were often—count ’em—100 masses a week, plus a very active funeral and wedding schedule. Six full-time priests and a small army of general staff kept it all going. I remember the rows upon rows of votive lights plus, on the weekends, ushers stationed in the aisles to make people push in deeper so they could seat one more parishioner. All this and absolutely no parking.

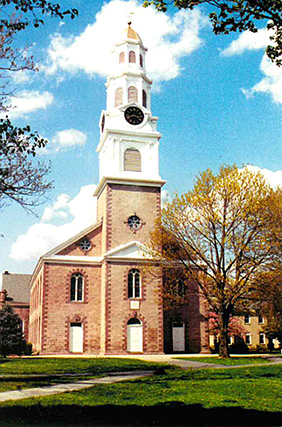

Fast-forward to 2010, when we were called to Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church on West 42nd Street in Manhattan. They were about to launch a major makeover of the interior when the contractors decided that the organ had to be removed as the work effort included the choir loft. We cleared our schedule and got the organ out the next week. It was a 1933 three-manual, 29-rank Aeolian-Skinner that, like so many of its sisters in Catholic churches, had been played nearly to death. In places the ivories were worn through to wood. The exterior console cabinetry looked like just what it was—command central for a workhorse instrument. Besides all the coffee cup stains, it had battle scars from the singers and instrumentalists who through the decades had positioned themselves around it while providing music. Swell-shoe rubber had holes like the bottoms of old shoes, and, for some unknown reason, the high G pedal key was totally missing! The Choir division had experienced enough roof leakage to be shut off, and under nearly 80 years of city dirt, the five-horsepower blower was dutifully still running—yet more testimony to the quality of Spencer Turbine’s products. But out it came. Organist Charlie Currin’s good stewardship had convinced a small contingent to stand up for saving and reconditioning their musical treasure, and the organ went off to our Connecticut shops fully expecting a complete overhaul.

But the sanctuary project took precedence, and any monies earmarked for the organ instead went into the black hole of unforeseens that come with such an old building, the oldest on New York City’s famous 42nd Street. Confident that an angel could be found or that money could be raised, we placed the organ in temporary storage in the form of a container on our Tolland shop property. In time all the possible start-work dates faded into memory. When the church’s beloved pastor, Father Peter Colapietro, became ill and passed away, the organ project seemed to disappear with him.

Months turned to years. Pastors came and went. In time, the diocese was seriously considering repurposing the building, a contingency that would need no organ. The Skinner’s size, specification, and pedigree brought interest from possible buyers. Surprisingly, the diocese expressed no interest in a sale. The decision to repurpose was dropped and yet another pastor was assigned. Our pleas to see the organ moved to proper storage were not heeded. At times, we’d open the container doors simply to air out the treasure of organ parts within. There were summers when the interior temperature went to 104 degrees, and of course Connecticut winters when it dipped below -13. We feared the roof might start leaking, as these container rentals aren’t famous for owner interest, certainly not in the form of roof repairs. Ten years later, there remained a few at the church who remembered Opus 908, but no takers for a rebuild.

I remember the moment driving on Interstate 84 when my phone displayed an incoming number with the NYC 212 area code. It was the then-pastor of Holy Cross, Father Thomas Franks. He seemed to know all about the Skinner and wanted me to know they were selling a tiny building near the church that would harvest the funding necessary to do the total reconditioning, even with some added costs resulting from storage issues. It was hard to believe, but it was true: Opus 908 would be saved!

In today’s pipe organ business, big jobs don’t happen too often; these days, not often enough. When one comes in, we call the entire staff together in the main shop and make the announcement. There are few more appreciated moments in our world. Everyone was painfully aware of the stored organ in the container, and we didn’t waste any time in swinging wide its doors to start removing the hundreds of entombed pieces.

We laid them out over hundreds of feet of open space in our Manchester shop. The realization of what had happened was sobering, to say the least. In places the container roof had leaked. There was mold—a lot of it. Even the thick Skinner swell-shade blades were delaminating. Some flute pipes were beyond hope. All four manual chests were opened and closely inspected. More than their grids were damaged; the chests would have to be replaced. Thankfully, the console had been warehoused and at least wasn’t water-damaged.

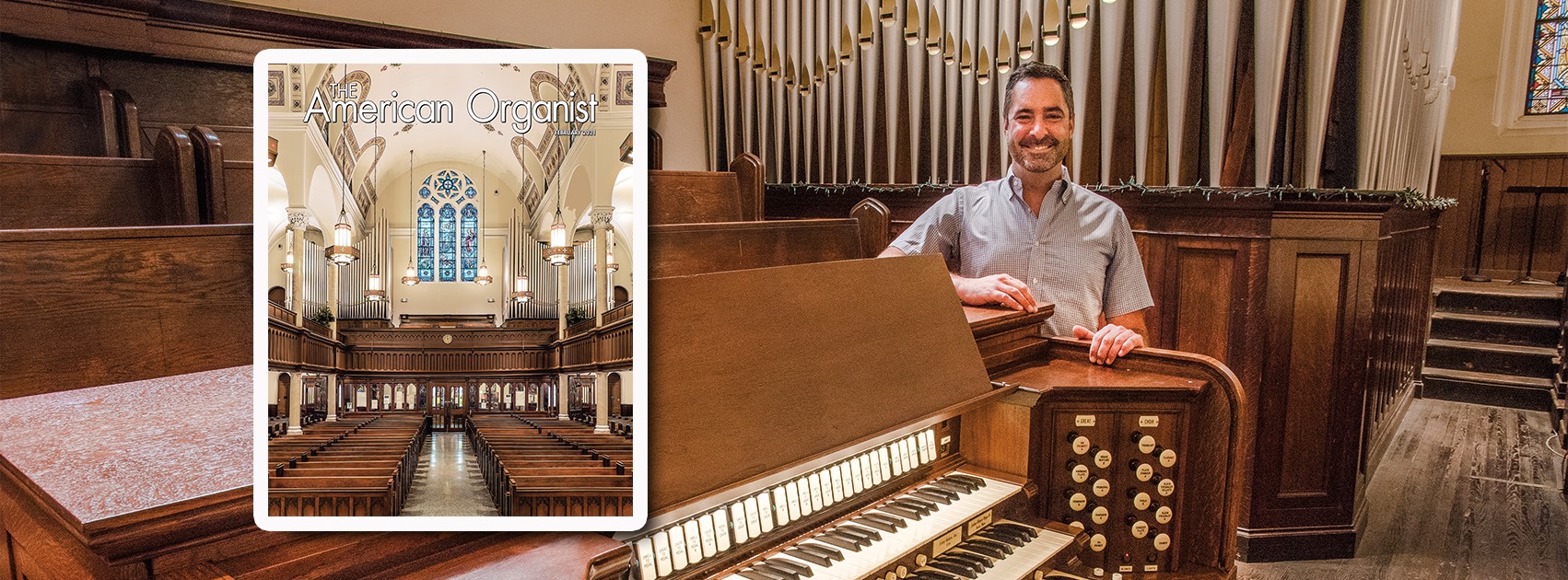

Could this organ be saved? You bet it could! At this point, Holy Cross had a new and ever-so-interested organist in the form of one young Tom DeFrancesco. Tom’s enthusiasm for the project shot out of his eyes, and every conversation left me ever so thankful for such an important project addition.

So, away we went. Everything was opened, inspected, repaired where necessary, releathered, and 100 percent renewed. The same occurred with all the reservoirs and tremolos. New replica manual chests reused the original chest top boards, double-primaries, and stop boxes. All 36 shade blades were reconditioned. This included the very evident lamination issues. Every reservoir was stripped down to a carcass and every interior wood joint sealed with leather stripping to be sure the seams would remain sealed during possible future movement of the wood. I didn’t think it was possible, but many of the metal pipes had taken on a corrosive exterior. As a result, their washing took about three times longer than usual. A bottom octave of zincs could take a day’s time to be properly made ready for a clear-coat sealer. Thanks to their copper content, the chime tubes had turned green. The Swell Flute Triangulaire was beyond salvage. Luckily, Mike Quimby had a twin that we could purchase. All reeds went to Broome and Company for some miraculous work visually and tonally. Hundreds of feet of structural lumber were scrubbed clean. Almost all of Skinner’s wood wind-line flanges had delaminated. We made identical replicas. The metal linkages inside the swell engines became a project in themselves. There are 126 facade pipes. Four were missing at the time of removal and had to be replicated. Nearly all were dented and, rather typically, many ears were missing. We sent them to Organ Supply Industries for a total overhaul.

The organ’s tired state made us look at the very sad but very dry console with excitement for its complete redemption. In comparison with the effort necessary with the chassis, the console’s main issues were with its exterior wood. These surfaces responded beautifully to our cabinetmaker’s touch. The rest was pretty much business as usual. Skinner quality saw it become like new again. Then came another new pastor. Please read on.

Father Francis Gasparik took over the reins of one of the diocese’s oldest and neediest buildings. The sanctuary still looked great, but he realized that under and above all this were industrial-strength issues that needed industrial-strength funding. I could just hear it: probably something like, “And we’re spending how much on getting the organ fixed?” All that he saw at the time was a gaping hole in the choir loft and possibly one of the most pathetic electronic substitutes around. How could anyone not respect his outlook? Thankfully, reinstallation started about six months after his arrival. All the hundreds of spotlessly restored parts must have offered hope, and perhaps even some indication as to why organ work is so custom, so expensive. I think it was the installation of all those facade pipes wrapping around the rear gallery (he had selected the color) that offered all of us a glimpse of that light at the end of this seemingly endless tunnel. It was a good moment.

Once the organ was installed and playing, it was obvious to all that this was a special instrument. Tonally, it was the combined effort of E.M. Skinner and G. Donald Harrison. Its sound is as relevant today as it was in 1933. In 1934, noted author and consultant William H. Barnes reviewed the organ and predicted then that its specification would not grow old. To his thinking, it was an example of the best in organbuilding and in organ sound.

It is. It must be. How many organs could go through what this one did and live to tell about it? I’m just glad we did too.

Mike Foley is president of Foley-Baker Inc. Website

Cover photo: John O’Donnell