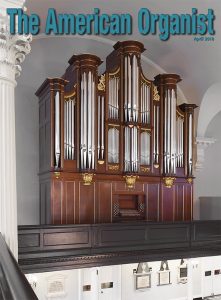

St. Paul’s Chapel

St. Paul’s Chapel

of Trinity Church Wall Street

New York City

Noack Organ Company • Georgetown, Massachusetts

View an enlarged cover

View the stop list

View a sample week of music-making at Trinity Wall Street

From the Director of Music and Arts

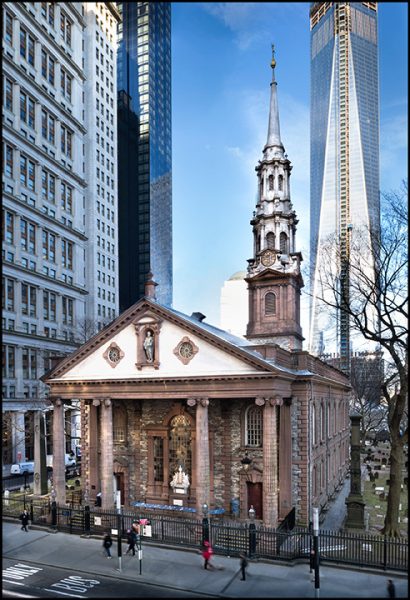

From my first day at Trinity Church Wall Street, I have urgently desired to see world-class pipe organs reinstalled in Trinity’s three liturgical spaces—not merely our iconic 1846 Richard Upjohn building at the intersection of Broadway and Wall Street and its attached All Saints Chapel, but also in St. Paul’s Chapel, Trinity’s second functioning church home dating from 1766, five blocks up from Trinity Church at Broadway and Fulton Street. To my core, I believe that living, breathing instruments are the best way to support living and breathing human beings in worship and song. The arrival of the Noack at St. Paul’s is the first and very happy step in this process.

To make music at Trinity Church Wall Street is to work in an atmosphere of rare privilege. Having grown up under the tutelage of Anthony Furnivall at St. Paul’s Cathedral in Buffalo and then with Gerre and Judith Hancock while a boy chorister at the St. Thomas Choir School, I had excellence in liturgy and sacred concert modeled and instilled in me from a young age. It’s difficult to express adequate gratitude for those wonderful mentors who helped prepare me at such a young age for this auspicious position in lower Manhattan.

For centuries now, Trinity Church Wall Street (and the chapels formerly and currently under Trinity’s leadership) has always endeavored to provide excellence in music, both in liturgical form and in a secular concert setting. Indeed, these buildings and the art created within them have provided the example to countless others, from the apocryphal American premiere of Handel’s Messiah to the wildly outside-the-box 1846 Erben organ, some of its keyboards six and a half octaves in compass (!). In the 20th century, the parish always supported abundant fine music, with such luminaries as Larry King, Channing Lefebvre, and George Mead always striving to provide the highest quality, both of musicianship and innovative programming. As a young student, I fondly remember enjoying Trinity’s recordings of Leo Sowerby’s complete choral works (the albums having been recently acquired by my then-roommate, Peter Krasinski).

In 2010, when I was called to Trinity in the newly created position of Director of Music and the Arts, my mandate was clear: build on the recent initiatives of organist/director of music Owen Burdick and “Concerts at One” artistic director Earl Tucker to reinvigorate and recast Trinity’s centuries-old professional music offerings into an internationally recognized performing arts center in New York City. This goal could be achieved by coupling secular and sacred offerings into a single coherent direction with a common mission. As part of this vision, new ensembles and programs were created, namely “Bach at One” (a weekly presentation of the choral works of J.S. Bach), “Compline by Candlelight” (a weekly Sunday evening service of improvised polyphony), NOVUS NY (Trinity’s contemporary music orchestra), Trinity Baroque Orchestra, and “Pipes at One” (featuring St. Paul’s Chapel’s previous Schlicker), and the Time’s Arrow Festival, an annual offering that juxtaposes music of our time with the ancient past. Most events take place at St. Paul’s Chapel, the perfect venue for intimate, spiritually rich concerts and liturgies. As we began to present these offerings at St. Paul’s, however, it soon became clear that the Schlicker, with its heavy mechanical action, was neither large nor varied enough to fulfill the needs of this growing liturgical and concert venue.

Most recently, and particularly under the leadership of our rector, the Rev. Dr. William Lupfer, Trinity has committed to an even deeper outreach in many directions: liturgical, community, social justice, music, and arts. In each of these areas, Trinity has redoubled its efforts to serve lower Manhattan. The response is timely, for this part of New York has seen tremendous change. What was once almost exclusively a business region has become, perhaps unexpectedly, a thriving neighborhood of younger people and families. As a result, both at Trinity (four services on Sunday, four services each weekday) and St. Paul’s (three Sunday services) we have more families and young people attending worship than ever before.

Early in my tenure, we did some preliminary work related to commissioning new pipe organs. Despite excellent efforts made by many, however, these initiatives did not take root. In 2015, we began afresh, convening a new committee—this time with active clergy and vestry participation. In June 2015, we brought Jonathan Ambrosino on board as project adviser. At his advice we created a traveling subcommittee, comprised primarily of myself, Jonathan, congregation members Scott Townell and Art Sikula, and the insightful participation of my colleague organist, Avi Stein. Working seamlessly between this traveling research committee, and the various vestry committees charged with investigating the viability of acquiring new instruments across the campus, was the unflappable William H.A. Wright II, a vestry member at both Trinity and at St. Thomas Church, where, as warden, he had been instrumental in guiding that parish through its process of commissioning the new Dobson.

In the usual course of researching organs and builders, we found ourselves in Boston looking at both new and older instruments. All along we had considered existing as well as new organs, and it turned out that for one particularly appealing historic instrument, we weren’t the only interested party. The other contender was Church of the Redeemer in suburban Chestnut Hill, which had decided their 1989 Noack wasn’t adequately supporting their music program. I knew this Noack well. I had practiced there while living in Brookline (during my ten-year tenure as university organist and choirmaster at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel). Later, after I got to Trinity, we used the Church of the Redeemer (it has terrific acoustics) as a recording venue for the Choir of Trinity Wall Street. Thus, after a few text messages and a quick detour, their director of music, Michael Murray, warmly welcomed us to see the organ again. In a flash, I thought it could work particularly well at St. Paul’s Chapel. Yes, the organ had some limitations, but at its core was an energy and conviction as appealing to me now as it was in the 1990s.

We knew the Noack would sound great at St. Paul’s, with its few shortcomings addressed and a few useful features added. We trusted that Didier Grassin’s reputation for visual mastery would bear fruit in handling the altered 1802 organ case. But none of us was quite prepared for just how very good and right it would actually be. The tone, the action, and the sheer physical beauty of the case have us all entirely captivated. Our gratitude goes to Didier Grassin, the dedicated Noack staff, and their extended collaborators, all of whom helped bring about this great gift to liturgy and music at St. Paul’s. The chapel now has an instrument that can support the level of performance we strive to achieve. Expect to see another happy feature in a few years, as the vestry voted unanimously in December 2017 to bring back pipes at Trinity Church!

Julian J. Wachner, FAGO

From the Consultant

In June 2015, when Julian Wachner and the Rev. Phillip Jackson, the vicar of Trinity, asked me to a dinner to discuss new pipe organs at Trinity, I felt a rare sense of elation. Who wouldn’t want to help this storied place in such a process?

In short order, I had to confront my embarrassing ignorance about the Trinity of today. We all know about the famed Choir of Trinity Wall Street, but I knew nothing about Bach at One or the improvised Compline. I understood that children were active at Trinity (more than 100, I would learn), but had no knowledge of the church’s extensive education and outreach program to youth throughout New York City. Given what the Rev. Dr. William Lupfer stressed while dean of Trinity Cathedral in Portland, Oregon, it wasn’t surprising that his becoming rector at Trinity would see an increased engagement on social justice issues. But the range and extent of Trinity’s involvement in this regard is truly staggering. It became clear on my many visits to the church that the number of visitors to each place was undeniable, with tourists and pilgrims often attending a comprehensive array of free musical programming by top performers. At no other church of my acquaintance is there music of such scope, from the wide range of liturgies or a Bach cantata at the lunch hour, to the world premiere of an opera or a newly commissioned Mass setting.

Fast forward six months to a December morning when Julian, Avi Stein, and I made what seemed like a lark visit to Chestnut Hill. When Julian suggested the Noack as a candidate for St. Paul’s Chapel, I had some information at hand. Two years earlier, Church of the Redeemer had hired me to survey the Noack and suggest options for moving forward. Thus began a process that led Redeemer to sell the Noack to Trinity and commission its own new organ (from Schoenstein, to be unveiled this month).

The entire prospect had echoes of another project for which I had served as consultant, at Church of the Incarnation in Dallas. There, in 1993, Fritz Noack fashioned his first modern essay in electric action, and a fascinating study in contrasts. The good things were particularly so, convicted and convincing, but other elements held the organ back from its full potential. In 2015, under Didier Grassin, Noack rebuilt the Dallas organ, honoring all that was good while recasting the rest. The result surprised everyone; we’d expected a good result, but this was distinctive.

While a much smaller organ, the Chestnut Hill Noack could answer to the same description. An unabashed, articulate Great chorus, topped by an equally unambiguous Trumpet, splashed its way into the room with a pure frisson. The remote Swell was less engaging, and, while interesting in concept, the small Choir seemed unrelated to the other departments in practice. The Pedal had something to say, but collapsing pipes compromised the effect.

By this time, I had worked long enough with Julian not to discount his hunches. Besides, relocating a used instrument seemed an intriguing way to start Trinity’s overall organ project. Certainly, both churches have had their share of instruments. At St. Paul’s, the first organ was imported from George Pike England in 1802 and fitted to a case by Johann Geib. In 1870, the Odells brought this organ into the modern age, widening the case, adding a swell box on top, and fitting a Pedal. In 1928, Skinner provided a new organ, which Aeolian-Skinner rebuilt in 1950; both versions retained Odell’s awkward penthouse Swell. In the tenure of George Mead and his assistant, Robert Arnold, a new mechanical-action Schlicker arrived in 1964. While Odell’s Swell never looked right, without it the case looked wrongly wide. The Schlicker was an important installation for New York in its day, but had proven unreliable and limited. The Andover Organ Company did some work on the organ in 1981, but fundamental engineering and action issues remained.

A few weeks after our visit to Boston, Trinity commissioned Noack to study how the Chestnut Hill organ might be resolved with the St. Paul’s case. As with the project in Dallas, Didier Grassin provided a sensible solution. He would accept St. Paul’s 1870 case’s width but correct its proportions by raising the center sections. Certain parts of the Chestnut Hill Noack would need making anew, but anything that didn’t could be checked over and re-implemented for installation in New York. In place of the original detached console (for which there was no room at St. Paul’s), a new attached keydesk would be fashioned. Those stops that had either failed mechanically or disappointed tonally would be replaced.

In the end, every decision, small and large, has contributed to the organ’s success: a new and far better swell box; the decision to reintroduce gilding; the remarkable new Swell and Pedal reeds; the addition of a disarmingly lifelike nightingale device, here cheekily called “Byrds.” Where before the Geib case seemed dusty and unimportant, now it rises like royalty, a fitting and majestic response to the gilded altar. I add my thanks to the Noack team and the many people at Trinity who supported this project.

Jonathan Ambrosino

From the Builder

Relocating an existing organ is notoriously difficult. The spaces usually do not match; they exhibit different acoustics, configurations, layouts, or even musical needs. Surely if a project should fail, it would be the relocation of a colorful 1989 Noack organ from a quiet and leafy Boston suburb to the hyperventilated Financial District of Manhattan, right on Broadway.

Indeed, there is little in common between the neo-Gothic architecture and live acoustics of Church of the Redeemer and the intimate atmosphere of historic St. Paul’s Chapel. Neither is there much in common between the original setting of the instrument, tucked deep in a chamber in Chestnut Hill, and its new home, a 1802/1870 mahogany case in New York.

One must admire Julian Wachner’s determination to see beyond appearances and his wish to bring to St. Paul’s Chapel the joy he had experienced playing that organ while living in Boston. It is not entirely surprising that Julian would find a kindred spirit in the colorful and energetic sounds Fritz Noack created in the original instrument. The challenge at hand was to transplant not only a set of pipes, or some kind of machinery, but the exhilarating experience and memories of a musician.

Still, an organ is made of windchests, reservoirs, windlines, mechanisms, and pipes. All of these would have to find a new place. There is no doubt that the biggest challenge Fritz Noack faced in 1989 was the conditions he found at Chestnut Hill: an unfortunate deep organ chamber. There was only so much a skilled and experienced organbuilder like Fritz could do to compensate. After all, no conductor or choir director would expect their singers or instrumentalists to give their best sound while shoved in a closet. However, this is what is expected from the organbuilder! The move to St. Paul’s Chapel allowed the three manual divisions to be reorganized more sensibly. The Great kept its prime position, up front and center, while the Choir, which used to speak behind the reversed console, is now perched at impost level, where it chirps happily. The Swell, which greatly suffered from lack of height and egress, now rises all the way behind the two manual divisions. Finally, the Pedal has been split into the traditional C and C#sides at the extremities of the case.

Surprisingly, little tonal rebalancing was necessary. It felt as if the pipework had just been waiting to be given a proper spot. With an enlarged and redesigned swell box, we were able to revisit the Swell reeds. The result is an organ that has gained a far wider dynamic range while retaining its original colors. I believe the multiple facets of this instrument will surprise many, and I anticipate seeing how far the expansive music program at Trinity Church Wall Street will push the organ’s tonal envelope.

A new chapter in this instrument’s life is starting. New memories and new experiences are being created. There is nothing more an organbuilder could hope for.

Didier Grassin, President

Noack Organ Company

Eric Kenney, Dean Smith, Mary Beth DiGenova, Evan Fairbanks, Brett Greene, Aaron Tellers, Ian Esmonde (Noack staff)

Amory Atkins, Terence Atkin (on-site assistance)

Terry Shires (facade pipes and new reeds)

Joshua Sidlowski (case gilding)

Laurent Robert (new carvings)

Jean-Sébastien Dufour, David Rooney, Didier Grassin (voicing and tonal finishing)