A Kimball in the Wilderness

A Kimball in the Wilderness

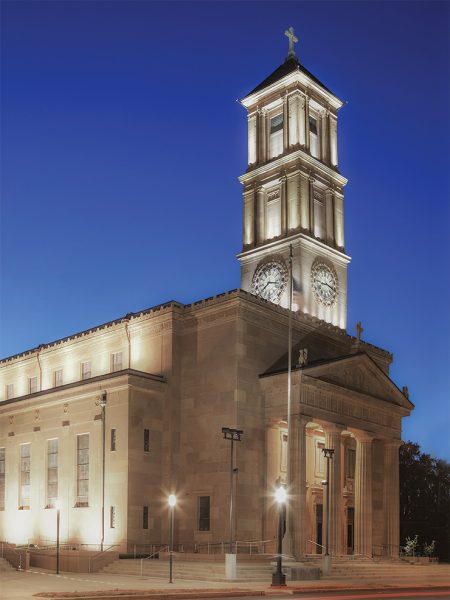

St. John’s Cathedral

Denver, Colorado

Chancel Organ

W.W. Kimball 7231 (1938)

Restoration by Spencer Organ Company Inc. (2009–2012)

Gallery Organ

Spencer Organ Company Inc. and J. Zamberlan & Co. (2016) New Antiphonal Organ with Vintage Pipes

The chancel organ at St. John’s Cathedral is Colorado’s biggest pipe organ, the last large surviving Kimball, and a memorial to notable Denverites. The gift of Senator Lawrence and Margaret Phipps, the Kimball is placed in memory of Mrs. Phipps’s father, Judge Platt Rogers (1850–1928), mayor of Denver 1891–93. Judge Rogers died on December 25, 1928, leading Mrs. Phipps to envision a new organ in the Episcopal Cathedral in the judge’s memory ringing forth on Christmas 1937.

The Phippses were avid music lovers. Mrs. Phipps played the piano and organ, and had a 1933 Kimball at home—an instrument that was not delivered on time, irritating the senator, who had intended the organ as a surprise Christmas gift. Thus, to get Kimball back in the running for the Cathedral job, sophisticated nudging was needed, which came in the person of George Boothroyd. Close friend of the Phippses and organist at Grace–St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Colorado Springs (1928 Welte with 1936 Kimball additions), Boothroyd probably drafted the stoplist for the Phipps Kimball. When his rector, the Rev. Paul Roberts, was installed as dean of Denver, Boothroyd became the Cathedral’s de facto organ advisor.

Once again, Kimball promised quick delivery: 80 ranks in six months, by Christmas 1937. Even with production still high in the 1930s, this was a daunting schedule, not helped when Boothroyd kept adding stops, which the Phippses kept happily funding. The original 80 ranks eventually grew to 95; Kimball threw in a Choir 4′ Viola to make 96, all the while keeping to the Christmas deadline. When the first trainload kept not arriving, nerves began to fray: from local organ man Fred Meunier (a key part of the Christmas promise) to Senator Phipps (who hadn’t wanted Kimball in the first place), and especially Cathedral organist Carl Staps (piqued at having been kept at arm’s length). The senator even suggested optimal train routing for the first carload, containing the Swell and some of the Pedal. It finally arrived November 13, and Meunier got it playing for Christmas amid an atmosphere of heavy disappointment. Not until March 22 was the entire organ all in. Kimball head voicer George Michel had already begun tonal finishing on March 13, completing it on April 11 in time for Easter. Palmer Christian played the dedicatory recital May 18.

With the Phippses dismayed, the organ crew demoralized, and the dean and Boothroyd disappointed, Kimball still managed to claim pride in their achievement. Of course, George Michel was no Walter Holtkamp or G. Donald Harrison; the 1930s Kimball tonal palette remained firmly in the late Romantic Anglo-American canon. Michel’s signature came in balancing a serious interest in ensemble with ultra-refined voicing and sheer excellence of pipe construction. No American firm of the day made better pipes: elegantly formed from the finest materials, gloriously substantial without any industrial feel, with wonderful, sophisticated touches. The hard, rolled zinc is so sturdy that strings are planted on the main chests from 8′ C without any upright racking; not one miter or seam has failed. Michel also pioneered the use of organ metal (instead of zinc) below 4′ C; the Pedal Geigen here is in spotted metal from 8′ D.

The tonal design follows a pattern Kimball established at the auditoriums of Minneapolis (1928), Memphis (1929), and especially Worcester (1933). But where those earlier instruments employed manual unification, Denver has none. The Pedal has only six extended registers, and the independent chorus 32-16-8-4-IV-32-16-8-4 dominates the ensemble almost like a French organ, only with butter-smooth tone. The Swell stoplist comes straight from the Anglo-American playbook, enriched with a second Trumpet, a third ultra-soft string pair, and a delicate Cornet. The Choir shows some corporate character in the Diapason, Octave, Trompette, and mutations, but is as much about color painting with its superb imitative reeds and Viola chorus. The Solo contains

rich Gambas, bold flutes, two crowning Tubas, and the expected French and English horns.

Divided into a strong unenclosed chorus and supporting enclosed voices, the Great is Michel’s most interesting composition. The First Open is flared two scales for a brilliant tone of particular resonance. The Second is formed of traditional cylindrical pipes, while the enclosed Third is half-tapered with narrow mouths, as is its companion Second Octave. The other chorus elements match the Second; the Fourniture has higher pitches than one might expect, while the tierced Full Mixture echoes an idea of the 19th-century English builder T.C. Lewis. Both harmonic flutes switch from 1/4 mouths in the natural length range to 2/7 for the harmonic portion. The Bourdon’s metal portion starts out with solid canisters, then receives internal chimneys at middle C; the first four chimneys are tapered, to graduate the introduction of rohr color. The sassy 16′ Quintaton (wood bass, metal treble) is as extroverted and plucky as any 17th-century example, albeit with smoother speech.

The first restoration challenge of any Kimball is that these organs contain considerably more mechanism per stop than other contemporary builders of “straight” organs. One Skinner key primary can exhaust as many as 15 note pouches; a Kimball primary, no more than six. Each mixture rank has its own stop action, surely a tuner’s convenience but one that gives a Kimball Plein Jeu five times the mechanism and requires three times the space as a Skinner. Regardless of class or pressure, every enclosed manual pipe tremulates; partial-compass celestes or stopped basses on open flutes were reserved for the smallest Kimballs (or, perhaps in their view, the corner-cutting of others). Where Skinner and Aeolian-Skinner avoided manual relays, considering them costly, complex, and action-slowing, Kimball assumed switching stations as a given for all but the smallest instruments, and incorporated as many primaries or unit actions (even for straight stops) as necessary—all creating more mechanism to restore. In similarly sized Swells between Skinner and Kimball, the Kimball can present the restorer with twice as much work.

Below chest level, the terrain is daunting. Kimball customarily provided separate reservoirs for manual basses, to promote steady wind and limit the tremulant’s reach. Thus, Denver’s 96 ranks are fed from 21 reservoirs, where Yale’s Woolsey Hall Skinner has 25 reservoirs, but for 197 ranks. Above chest level, the landscape isn’t much roomier. Early on, Kimball developed a fast, individual-pneumatic shutter motor to allow rapid accents. In the 1930s, this system was refined with additional pneumatics for the first few shutters, making them open only partway at first for subtler crescendos. This burly machinery works gorgeously, but is often mounted directly over a walkboard, which any technician taller than four feet quickly notices.

When it came to cramming all of these reservoirs, shutter pneumatics, tremolos, open flute basses, and full-compass celestes into a chamber, Kimball’s fearlessness was unmatched. In 1936, after Kimball sold an organ to a new Massachusetts church, the architect took away a quarter of the available room. Without flinching, Kimball compressed the same 51 ranks to fit. For Denver, what trouble were 16 more ranks, among them two open 16′ flues and an independent 32′ reed? It is the most cramped organ any of us has worked on—excepting, of course, other Kimballs.

Eight decades on, the several-month delay in completion seems trifling against Kimball’s real achievement: solid and interesting flue choruses, purring flutes, deluxe strings, uncanny perfection of evenness and timbre in reed voicing, and a pervading yet non-booming bass. In this distinctive 1930s Kimball juxtaposition of clotted-cream reeds against edgy diapasons, warmth remains the touchstone. While one could never mistake this for an on-axis installation, still there is a clarity that belies the instrument’s shockingly cramped installation, thanks to having the Great chorus right behind the facade, and a lack of transepts.

Still, it’s not surprising to see the console prepared for an Antiphonal. Nothing is known about Kimball’s, Boothroyd’s, or Staps’s intentions here, but 21 knobs were provided for manual stops, another seven for Pedal, and seven tablets (all unengraved) to accommodate one large floating department with separate Pedal. In 1941, Kimball (or perhaps Fred Meunier using Kimball stationery) mooted three specifications, none of which could have fit in the gallery proper without blocking the wide central window. By this time, Mrs. Phipps’s mother had died, and she thought to complete the Platt Rogers Organ with an Antiphonal, thus honoring both parents. But, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 came an injunction that US organbuilders use, in the first three months of 1942, only half the amount of tin used in that same period the previous year, and then cease to use any tin after March 31, 1942. Although they could not have known it, Kimball produced for St. John’s their final statement of what a grand organ should be.

For years, the organ was maintained by its installer, Fred Meunier, succeeded by the Morel establishment, and then Norman Lane. Along the way, minor repairs and restoration were undertaken, with solid-state equipment superseding the original remote relays and combination machines. In the 1980s and 1990s, several efforts were mounted to rebuild and recast the instrument. Both times the Cathedral got close to a contract, however, the company in question entered into bankruptcy. By the time Stephen Tappe arrived in 2004, he had already shepherded a 1929 Skinner restoration in Jacksonville and was bent on restoration. An Organ Task Force, convened in 2007 (with Tappe, Janet Thompson, Norman Lane, Richard Robertson, Michael Friesen, Gregory Movesian, Michael Jalving, and Susan Tattershall), affirmed a commitment to restoration. Spencer Organ Company was selected in 2007, renovated the blower in 2008, and in 2009 entered into contract for the full restoration.

The project aimed to be as conservative as possible. All actions and reservoirs were releathered to the highest standard. The original lacquer finish on all pipes was preserved, without additional coats for cosmetic purposes. Wood pipes remained in Denver, out of concern that they might be compromised if exposed to the New England climate. Having been cleaned once in 1965, the metal pipes were in fine shape. After re-rounding, the original tuning sleeves were refit, including Kimball’s distinctive friction-taped larger ones. All of this work was done at Spencer according to protocols worked out by Joseph Rotella, Jonathan Ambrosino, and Martin Near. Near superintended the pipe restoration with particular reverence, having known the Kimball from boyhood when his father, the Rev. Kenneth M. Near, served as a canon there from 1985 to 1991.

In tackling this project, Spencer extended its own staff with a family of previous collaborators. A crew from the Organ Clearing House joined in the organ’s removal during June 2009. J. Zamberlan & Co. staff helped with preliminary preparation of windchests, sending them on to Spencer for the balance of the restoration process. Samuel C. Hughes reconditioned the 21 reeds, retaining the original brass wedges and tongues but fitting new metal inserts (archiving the originals). Richard Houghten and his assistant Vladimir Vaculik took charge of all console renovation and electrical work, updating the control systems to SSOS MultiSystem. The console’s curvaceous Moderne lines still resound to the puffing of the original electro-pneumatic drawknob and tablet actions, carefully restored and adjusted.

For the reinstallation, the Zamberlan crew joined up, now with Visser-Rowland alum Jim Steinborn in the mix. (Based in Fort Collins, he is now the organ’s curator.) Having reviewed all the flue pipes in Waltham, Jonathan Ambrosino undertook the site finishing with veteran voicer Daniel Kingman, whose first-week dictum—“There is only one way through this organ: slowly”—became a project motto. Paul Jacobs’s rededicatory recital on November 11, 2011, included a memorably panoramic interpretation of the Elgar Sonata.

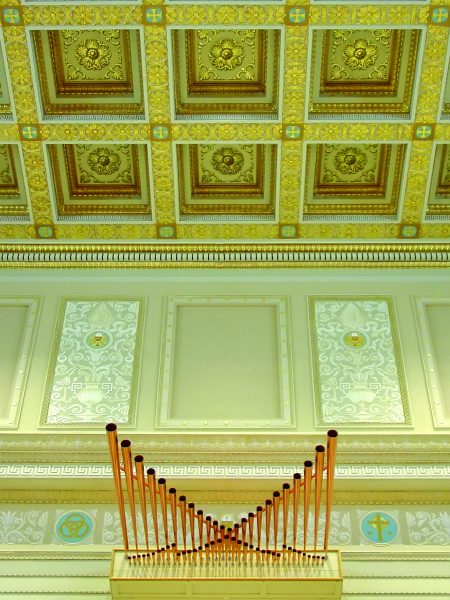

With the Kimball restoration under way, the task force continued to consider options in the gallery. All acknowledged that restoration would not magically transform the Kimball’s ability to lead a packed nave. Some of America’s finest builders put forth many intriguing possibilities, but what really captured the task force’s attention was news of a cache of 1899 Kimball pipework that had become available in Pittsburgh. Going on faith, Zamberlan and Spencer crews retrieved these pipes, while William Catanesye (at the time, a Spencer employee) sketched out a case design, taking certain cues from the chancel facade and inspiration from the chaste twin gallery case-fronts of a 1908 Hook & Hastings in Beverly, Mass., that Spencer had restored in 2006. In the end, Joe Zamberlan designed the Denver cases and organ afresh, but it was that initial drawing that sparked imaginations and sold the project.

Stephen Tappe had clear expectations for the Antiphonal. Naturally, it should aid congregational leadership, but also contain sufficient material to support the choir from the gallery. Finally, it should provide a few key effects the chancel organ lacked: soft 32′ and heraldic manual reed. Most of the Antiphonal pipes come from the Pittsburgh Kimball, which, it must be admitted, hails from a different aesthetic than the chancel organ. These pipes are voiced on 3¼” wind pressure and reflect a late 19th-century approach to construction and voicing. As Kimball’s pipe shop was in its infancy in 1899, some of the Pittsburgh pipes came from suppliers. The tin strings from G. Mack (a former Roosevelt pipemaker) are incisive in timbre yet delicate in strength. The diapasons resemble those of Carl Barckhoff, with healthy windways and slightly arched cutups. The Kimball-built, sprightly-toned stopped wood flutes recall Woodberry or Johnson, as do the thin, blending Trumpet and Oboe. Non-1899 registers are the Great Gemshorn (a fine Tom Anderson rank salvaged from another Spencer restoration) and new pipes from A.R. Schopp’s Sons. Schopp voicer Bob Beck did excellent work on the prompt facade Diapason, Violone, and 32′ Bourdon. For the Tuba, we turned to the magical touch of Christopher Broome. Scaled on the Skinner pattern and hooded from tenor F-sharp, the Tuba has a darker tone in deference to the chancel organ.

The Spencer and Zamberlan shops collaborated actively. The two Josephs co-designed the layout, windchest style, and wind system. Cases, structure, windchest parts, reservoirs, and blower cabinets were built at Zamberlan’s. The Spencer shop leathered the windchests and completed them with restored pipes, racking and testing. Everything was returned to Ohio for setup, and then sent on to Denver for installation. Jonathan Ambrosino helped with concept and tonal design, and did voicing work on flue pipes and the Vox Humana, which Martin Near, once again, put into beautiful condition. Sam Hughes reconditioned the Trumpet and Oboe. Spencer renovated a 1952 two-manual Aeolian-Skinner console with new tablets, expression shoes, and pistons. Houghten and Vaculik returned to update the entire organ to MultiSystem II, while SSOS provided a special touch-screen portal that permits the setting of chancel generals at the Antiphonal console without having to run downstairs.

Life sometimes imitates life. Without any specific intention, the narrow cases impart an unmistakable Kimball feel to the new Antiphonal, apparent as one squeezes and scrapes through an instrument that may not have arrived precisely on schedule. Thankfully, this time around the Cathedral has been incredibly patient and thoroughly supportive. Everyone is pleased, even relieved, at how natural the cases look, how unviolated the window remains, and how finished the gallery now appears. The tones from the Antiphonal are surprisingly gentle in the gallery proper. But with their ideal location against hard stone, these pipes sound full and clear in the nave, answering the chancel organ with a contrasting, respectful palette of color. The sum effect fills the room as never before. These various qualities were on good display at a gala concert last September, when Princeton University Organist Eric Plutz (who served as assistant organist at St. John’s in the 1990s) returned to grace the chancel console, with the Cathedral choir in the gallery led by Stephen Tappe and Lyn Loewi at the organ.

A project of this magnitude involves many hands. We are grateful to our staffs and colleagues whose myriad talents enriched the results. And, even as these projects presented as many challenges as rewards, this beautiful building has cradled us in our efforts. On and off now for a decade, we have entered this nave, its limestone walls marbled in a thousand hues of Connick blue, understanding that such an environment issues its own commandment to excellence. Kimball may have missed their deadline, but they stopped at nothing to shoot well past the mark. We hope our work is worthy of theirs and of this great Cathedral.

Joseph Rotella, President; Spencer Organ Company

Joseph G. Zamberlan, President; J. Zamberlan & Co.

Jonathan Ambrosino

Plainfield United Methodist Church

Plainfield United Methodist Church

St. Cecilia Catholic Church

St. Cecilia Catholic Church