Ladue Chapel Presbyterian Church, St. Louis, MO

Schoenstein & Co., Benicia, CA

By Jack Bethards

“A dignified and churchly ensemble” described Ladue Chapel’s new Kilgen organ in the December 1951 dedication program. This was a special year for the St. Louis organ firm—its centennial. Author, organ consultant, and organist William H. Barnes was the recitalist. Solo repertoire, although featured on the opening program, was clearly of minor importance in the full scheme of the church music program. This was a church organ.

Not too many years later, church organists were being advised by the academic community that they were being short-changed with instruments that were caricatures—not much better than theater organs. The great organ solo repertoire, they said, was being either ignored or butchered in churches. After all, no one makes special pianos—nor violins, flutes, or other instruments—for churches. Shouldn’t the organ be made properly to accommodate its own music? Certainly any organ capable of playing the great masters should be able to accompany. Accompaniment became a secondary consideration if any at all.

By 1970, the pressure to install “proper” organs in churches was great, and Ladue Chapel went full steam ahead with a mechanical-action organ of 40 stops, 59 ranks from Werner Bosch Orgelbau of Kassel, West Germany. This organ was special for its builder just as the Kilgen was. It was number 500 and called the “Jubilee” organ. The program description boasted that it would play “organ music from all periods, from Baroque and the majestic music of Bach to the 20th-century rhythms of Bernstein.” This instrument was the quintessential modern interpretation of the North German Baroque style. As time went on, the “dignified and churchly” tone of the old Kilgen was missed more and more.

Over the years, this organ went through major changes twice, in an effort to increase its versatility for the continually growing music program. Finally, by 2013, it was decided that further attempts at change would be unproductive and a new organ should be built that not only had “churchly and dignified” tone, but also was large enough to be capable of giving a reasonable account of the wide range of solo repertoire. Once again, accompaniment was first and repertoire was second in line—but not quite as far back as in 1951.

We believe there is such a thing as a church organ—an instrument specialized for church use, where accompaniment takes precedence. For a small instrument, this means tough choices—for example, leaving out a mixture in favor of a mezzo forte 8′ voice, such as a string celeste. In a larger instrument, it means adding things over and above what is required for basic repertoire—such as specialty color reeds, one or even two “extra” celestes, and a commanding solo reed, such as a Tuba. It means having more of the organ—in fact, as much as possible—under expression. All these “additions” are unnecessary for the repertoire-specific organ; therefore, it could be said that the church organ is a much more complex instrument since it must produce a wide dynamic range, an exceptional variety of tonal color, and also great power, when needed, to accompany a large congregation. In addition to musical accompaniment, much of which is transcribed, a church organ is sometimes called upon for improvised accompaniment of the “dramatic action” of the service. It must be a nimble vehicle for the creative organist.

Most important of all, a church organ must have the ability to capture and hold the interest of listeners and musicians over a long period of time. It is perhaps the only instrument heard by and played by the same people week after week, year after year, and sometimes generation after generation. If it doesn’t have enough variety and the ability to make a strong emotional connection—to celebrate joy, to comfort in grief—it is a failure. The church organ has a heavy musical job to accomplish, and its most important characteristics are versatility and beauty.

If an organ has these qualities, shouldn’t it be able to render the solo repertoire as well? There is no hope of such an organ playing any branch of the repertoire with absolute authenticity—that is, with the sounds that were envisioned by the composer; but it is certainly possible for it to render the scores musically if it has the proper tonal architecture. By that I mean the traditional distribution of tonal families in each division at the appropriate pitches—the organ’s “instrumentation.” I make the comparison with the symphony orchestra. Certainly, a large orchestra in a large hall with modern instruments cannot play Mozart or Beethoven with the authenticity that can be captured by a specialized early-music ensemble, but it can render musically satisfying performances because its instrumentation fits that of the score. The same can be true in the world of the organ. In the church setting, authentic performance practice is not a requirement; but the ability to accompany the services, render solos musically, and project “dignified and churchly” tone are.

Jack Bethards is president and tonal director of Schoenstein & Co.

Challenges and Partnership

Well over half the success of this instrument must be credited to the people of Ladue Chapel Presbyterian Church. An organ can be a musical jewel; but without the right setting, it can never sparkle. Providing that setting was a huge challenge, met fully every step of the way by the church.

The primary hurdle was finding space for the comprehensive instrument that the music program warranted. The former organ had made a kind of tunnel around the east end window, with its cases dominating the chancel. It was felt that this distraction should be eliminated. The only alternative was to use the original chambers at the sides of the chancel. Unfortunately, they were less than five feet deep and lacked the height for full-length 16′ pipes; plus, the chamber floors were not strong enough to carry the weight of a large instrument.

Although this was an unexpected challenge, the church immediately agreed to have the chambers completely reconstructed and raise the ceilings as far as possible to provide the maximum space. Even with these additions, there was still no space for a 16′ Open Wood stop. Plans for the chancel modification were changed to include a large central space behind the choir for these pipes to be arranged horizontally below the Willet stained-glass window. The organ is placed in four locations: Great and Choir in the right chancel chamber, the Swell and Pedal in the left, the Open Wood at the east end, and Echo at the west.

The next step was acoustical improvement. Acoustical consultant Scott Riedel was engaged and provided guidance on all phases of this work that were executed with care by the church. This included not only improving the acoustics in the worship space but also insulating against outside noise, such as the large condenser unit located just beyond the chancel wall.

An outstanding team of local craftsmen, headed by BSI Constructors’ manager Rob Beaulieu, implemented all preparations for the organ precisely and with great alacrity. The architect was Gary Dedke, and the project manager was Peter Benoist, president of Hercules Construction Management. The organ cases were built and installed by New Holland Church Furniture. Church administrator Vicki Hampton directed all of this brilliantly.

The organ committee, chaired by Douglas Wilton, deserves special mention. Their selection process was in-depth and meticulous. They then followed through to be sure that everything we needed was provided. It was a true partnership. Of course, at the center of the whole process was David Erwin, director of music. His advice and support were of great value, from the initial stoplist discussions through the tonal finishing.

The completed organ was first used on Reformation Sunday, October 25, 2015. It will be dedicated on March 6, 2016, in a recital by Scott Dettra of Dallas, Texas. This was a very pleasant project from beginning to end. Throughout, we felt like members of the Ladue Chapel family.

—Louis Patterson

Vice President and Plant Superintendent, Schoenstein & Co.

All photos by Louis Patterson

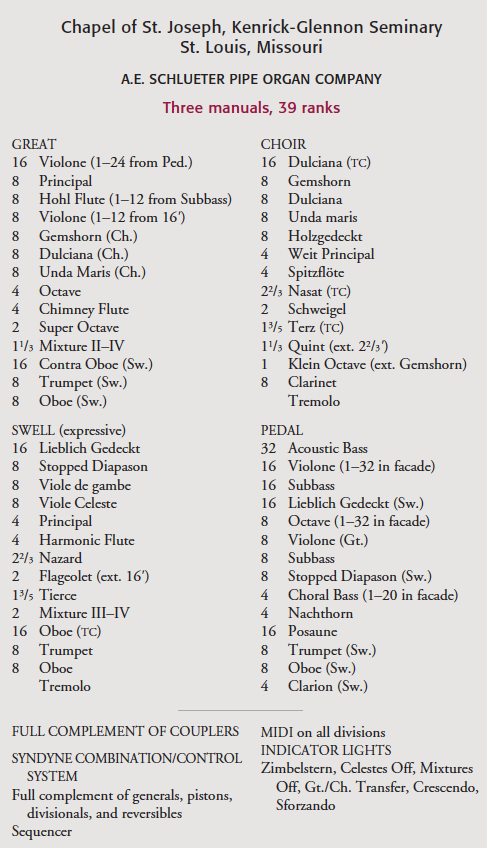

Our formative discussions about the tonal design of the Choir had considered two classes of strings. There was an equal case to be made for the foundational hybrid Gemshorn and for the weightless Dulciana. In the end, through the donations of our family, we decided that these were not luxuries but necessities, and both were included.

Our formative discussions about the tonal design of the Choir had considered two classes of strings. There was an equal case to be made for the foundational hybrid Gemshorn and for the weightless Dulciana. In the end, through the donations of our family, we decided that these were not luxuries but necessities, and both were included.

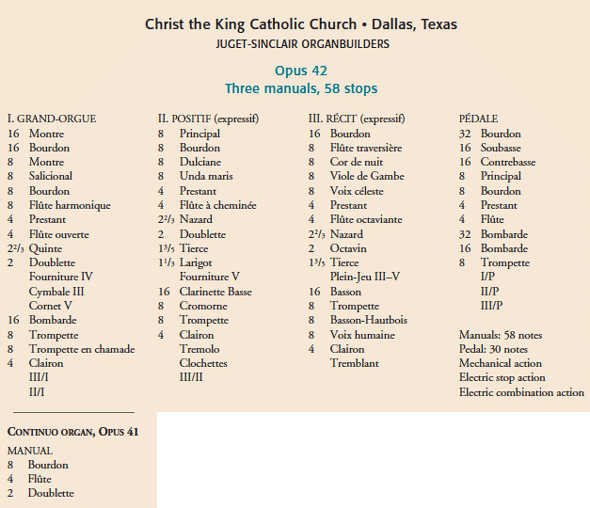

It wasn’t an aha moment that led us to a solution. It was more a case of the elimination of doubt—as crazy as it seemed, we could see no downside to our proposal: a three-manual, French-Romantic-inspired instrument, with Grand-Orgue and most of the Pédale division against the back wall, supported entirely by two beams that traverse the gallery. Both Récit and Positif would be in swell boxes occupying the chambers to each side, but cantilevered and angled into the room to promote projection. The console would be detached, with trackers running above the existing concrete choir risers, but below new oak risers. Trackers to all divisions would scale the three walls of the choir loft, taking practically no room from the choir. Our previous experience told us that we could

offer this solution happily—there would be no compromise in the success of the action, the projection of each division, choir seating, or access for maintenance. It just seemed so unusual that it required the methodical elimination of doubt for us to feel comfortable floating the proposal. If the instrument seems natural now, it didn’t then.

It wasn’t an aha moment that led us to a solution. It was more a case of the elimination of doubt—as crazy as it seemed, we could see no downside to our proposal: a three-manual, French-Romantic-inspired instrument, with Grand-Orgue and most of the Pédale division against the back wall, supported entirely by two beams that traverse the gallery. Both Récit and Positif would be in swell boxes occupying the chambers to each side, but cantilevered and angled into the room to promote projection. The console would be detached, with trackers running above the existing concrete choir risers, but below new oak risers. Trackers to all divisions would scale the three walls of the choir loft, taking practically no room from the choir. Our previous experience told us that we could

offer this solution happily—there would be no compromise in the success of the action, the projection of each division, choir seating, or access for maintenance. It just seemed so unusual that it required the methodical elimination of doubt for us to feel comfortable floating the proposal. If the instrument seems natural now, it didn’t then.

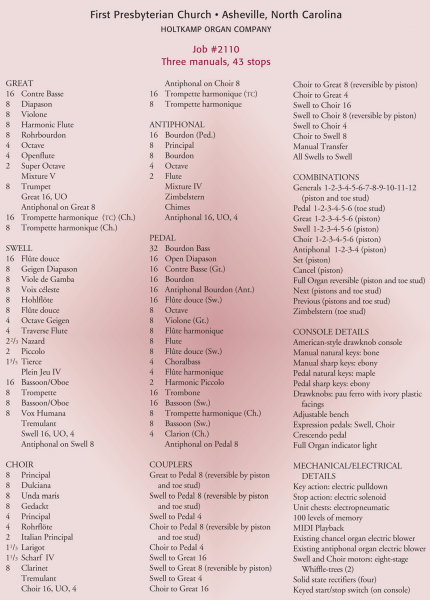

First Presbyterian began investigating the possibilities of organ restoration or replacement of the existing instrument in 2004. Early on, it was recognized that in order to effectively lead the congregation and project into the worship space with the true color and clarity of the pipework, the organ needed to be moved out of the side chamber and into the chancel area. This decision was followed by the formation of the Organ Search Committee in 2007. After hearing instruments from a number of different builders, the committee selected Holtkamp.

First Presbyterian began investigating the possibilities of organ restoration or replacement of the existing instrument in 2004. Early on, it was recognized that in order to effectively lead the congregation and project into the worship space with the true color and clarity of the pipework, the organ needed to be moved out of the side chamber and into the chancel area. This decision was followed by the formation of the Organ Search Committee in 2007. After hearing instruments from a number of different builders, the committee selected Holtkamp.

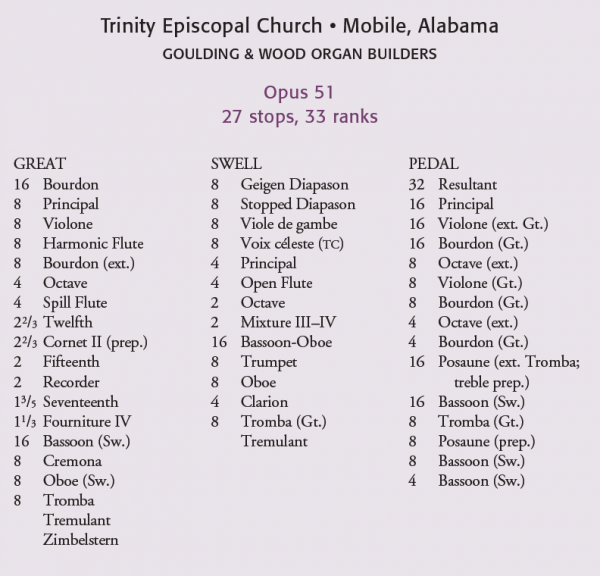

Mobile, Alabama, saw severe, unusual weather on Christmas Day 2012, culminating in a destructive tornado. This Gulf Coast town, more accustomed to dealing with hurricanes, suddenly faced dealing with the precision damage unique to tornados.

Mobile, Alabama, saw severe, unusual weather on Christmas Day 2012, culminating in a destructive tornado. This Gulf Coast town, more accustomed to dealing with hurricanes, suddenly faced dealing with the precision damage unique to tornados.