Christ the King Chapel

St. John Vianney Theological Seminary

Denver, Colorado

Kegg Pipe Organ Builders • Hartville, Ohio

By Charles Kegg

View the Stop List

View the Mixture Compositions

Every new pipe organ project, large or small, has a unique sense of importance. Rarely are we afforded the opportunity to build an instrument that will inspire generations of clergy to high ideals. Our new organ at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary is a rare honor for an organbuilder. The goal we shared with associate professor of sacred music Mark Lawlor was to build an instrument suited primarily to the multiple daily Masses of the seminarians.

The failing electronic organ from 20 years ago had “replaced” the original 1931 Kilgen pipe organ. Heavily damaged first by modifications to the stoplist with foreign pipes installed by lesser hands, then with loud speakers among and largely on the pipes, the original pipe organ was assumed destroyed. When Kegg representative Dwayne Short first crawled into the crowded, dark, and dirty space, he made his way into the furthest reaches where few had ventured in years, to discover that many of the Kilgen Swell stops had survived in reasonable condition. These along with one Pedal stop and an orphan Great Clarinet gave us some original pipes to consider retaining in the new organ.

Christ the King Chapel is a handsome room built in 1931. Beautiful to look at with masonry walls and terrazzo floors, it is a child of its time, apparent when one looks up. The coffered ceiling panels are elaborately painted acoustic tile, rendering only about one second of reverberation when the room is empty. The organ is at the rear of the room, in a shallow chamber over the main door. The robust all-male congregation is mostly at the front of the nave and in the crossing. All these elements dictate a rich, strong, and dark organ to meet the voices at their pitch and location. There is an Antiphonal that is prepared in the console. Until it is installed, the main organ will have to fill the room from the rear with the singers up front.

Dr. Lawlor specifically requested that all manual divisions be enclosed to afford him and future musicians maximum musical flexibility with regard to accompaniment. Vocal accompaniment is always a priority in Kegg instruments, but here this element is paramount. It seems most organists prefer a three-manual organ to two, which we frequently offer in organs of this size. The new organ is 19 stops and 25 ranks dispersed over three manuals and pedal. The only unenclosed stops are the Pedal Principal 16′, from which the facade pipes are drawn, and the horizontal Pontifical Trumpet, in polished brass with flared bells. This last stop was also a specific request. Because the room is not excessively tall, these pipes are placed as high as possible. The large scale, tapered shallots and 7˝ wind pressure give these pipes a round, Tuba-like quality which is commanding and attractive. It has a limited compass, beginning at C13 for 39 notes to D51.

The Great/Choir and Swell are enclosed in separate expression boxes. The stoplist is not unusual, but the execution of the Principal choruses is. Both choruses have mixtures based at 2′. This allows them to couple to the Pedal without a noticeable pitch gap in the bottom octave sometimes heard with 1⅓’ mixtures. The breaks of these two mixtures are different (as seen in Fig. 1). The Swell Mixture breaks before the Great, bringing in the 2⅔’ pitch early. This gives the Swell Mixture a rich texture, particularly helpful in choral work. Emphasis in finishing is on unison and octave pitches when present. The first break in the Great Mixture is at C♯26 and from C♯14 is one pitch higher than the Swell, making it relatively normal. For the Great Mixture, the upper pitches are given more prominence during finishing. The two choruses complement and contrast well in this intimate space, without excessive brightness.

Many of the flutes and strings were retained from the original Kilgen organ. With some attention in the voicing room, these work well within the Kegg tonal family. Having heard other examples of our work, there was a keen desire by Dr. Lawlor for a new Kegg Harmonic Flute. To make this happen within the budget and space available, we used an existing wood Kilgen 8′ Concert Flute for notes 1–32. At note 33, this stop changes to new Kegg metal harmonic pipes. The stop increases in volume dramatically as you ascend the scale. Available at 8′ and 4′ on both the Great and Choir manuals, the 8′ stop is nicely textured and mezzo forte. The treble of the 4′ morphs into a soaring forte voice, made even more alluring by the tremulant.

With the exception of the Clarinet, all the reeds are new Kegg stops and typical of our work. The Trumpet has a bright treble and a darker, larger bass extending into the Pedal at 16′. The Oboe is capped and modeled after an E.M. Skinner Flügelhorn. The lovely Kilgen Clarinet fits nicely into the Kegg design.

The Pedal has the foundation needed for the organ. The 16′ Principal unit of 56 pipes provides stops at 16′, 8′, and 4′. This is the only flue stop that is not under expression. It grows in volume as you ascend the scale and does so more than its manual counterparts. Because of this, it is easy to have the Pedal be independent and prominent when needed for polyphonic music. This stop joins the Great Principal and Octave, all playing at 8′ pitch, to make the 8′ Solo Diapason III, a Kegg exclusive. With three 8′ diapasons at one time, it is similar in effect to a First Open for both solo and chorus work where a firm 8′ line is required.

The console provides all the features expected in a first- class instrument today including unlimited combination memory, multiple Next/Previous pistons, bone and rosewood keys, and, of course, the Kegg signature pencil drawer and cup holder.

The original 1931 organ was covered by a gray painted wood and cloth grille. The new organ facade design was inspired by the building’s age and funds, but mostly by the significant stone door that dominates the rear wall. This is not a formal case, but it is more than a simple fence row. The stone door is massive and will always be visually dominating, so it was natural to acknowledge it and build from it. The center facade section pipe toes sit atop the lintel with the tops dipping down to mirror the brick arch above, making space for the Pontifical Trumpet to seemingly float. The center section sits 5˝ behind the side bass sections, giving more depth to the visual effect. Viewing the facade from any angle other than head-on, it becomes sculptural.

This was an exceptionally exciting and enjoyable project for us. The enthusiasm, interest, and complete cooperation from the seminarians and staff were a daily spiritual boost for the entire Kegg team. This organ was installed in nine days, ready to be voiced, due largely to the excellent working conditions. Many thanks to Cardinal James Francis Stafford, the Most Reverend Samuel J. Aquila, archbishop of Denver, Mark Lawlor, and all our new friends at St. John Vianney.

Charles Kegg is president and artistic director of Kegg Pipe Organ Builders, which he established in 1985. The Kegg Company is a member of the Associated Pipe Organ Builders of America and Charles is a past president of the American Institute of Organbuilders.

The Kegg team:

Philip Brown

Michael Carden

Cameron Couch

Joyce Harper

Charles Kegg

Philip Laakso

Bruce Schutrum

Ben Schreckengost

Dwayne Short

SS. Simon and Jude Cathedral

SS. Simon and Jude Cathedral

Duxbury, on the Atlantic coast 35 miles southeast of Boston, was settled by some of the original Mayflower Pilgrims. By 1632, a group including John Alden and Myles Standish left their small Plymouth farms and went north to work larger lots along Massachusetts Bay. In 1637, their settlement, having met the legal requirements to be set off as a separate community with its own church, was incorporated as Duxborough (original spelling), the second town in the Plymouth Colony. Elder William Brewster was the church’s first leader. The church embraced the Unitarian doctrine in 1828. The present 1840 Greek Revival meetinghouse, the fourth in the church’s history, retains most of its original furnishings. In 1851, the ladies of the church held their first fair to raise money for an organ and a fence around the cemetery. A Simmons organ was installed in 1853.

Duxbury, on the Atlantic coast 35 miles southeast of Boston, was settled by some of the original Mayflower Pilgrims. By 1632, a group including John Alden and Myles Standish left their small Plymouth farms and went north to work larger lots along Massachusetts Bay. In 1637, their settlement, having met the legal requirements to be set off as a separate community with its own church, was incorporated as Duxborough (original spelling), the second town in the Plymouth Colony. Elder William Brewster was the church’s first leader. The church embraced the Unitarian doctrine in 1828. The present 1840 Greek Revival meetinghouse, the fourth in the church’s history, retains most of its original furnishings. In 1851, the ladies of the church held their first fair to raise money for an organ and a fence around the cemetery. A Simmons organ was installed in 1853.

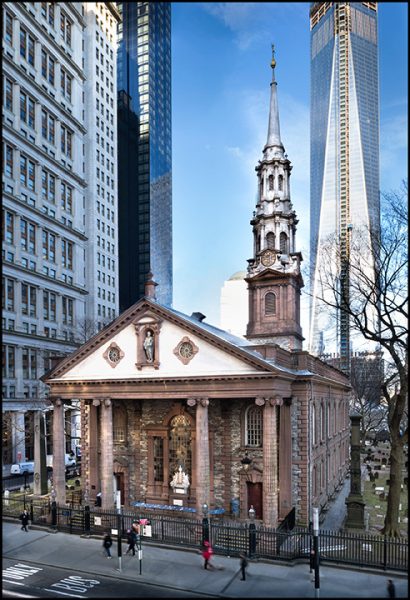

St. Paul’s Chapel

St. Paul’s Chapel

In the end, the scale model was the true author of the Christ Church organ and room modification designs. It guided us to many solutions, such as lifting the Erben case about 30″ on a new but formally paneled base, with confidence in how the upper case elements such as the large urns and center lyre with starburst would look relative to the vaulted ceiling. It enabled us to gain approval for the Chaire division on the gallery rail, and then to proportion its casework, position it fore and aft as well as vertically relative to the railing, develop its shape from a number of compartmental options, and fine-tune the scaling of the cornices, carvings, and even the under-paneling details.

In the end, the scale model was the true author of the Christ Church organ and room modification designs. It guided us to many solutions, such as lifting the Erben case about 30″ on a new but formally paneled base, with confidence in how the upper case elements such as the large urns and center lyre with starburst would look relative to the vaulted ceiling. It enabled us to gain approval for the Chaire division on the gallery rail, and then to proportion its casework, position it fore and aft as well as vertically relative to the railing, develop its shape from a number of compartmental options, and fine-tune the scaling of the cornices, carvings, and even the under-paneling details.