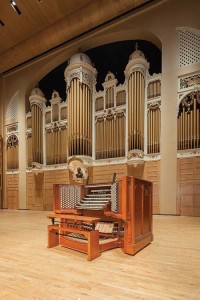

The Kotzschmar Organ, Merrill Auditorium, City Hall, Portland, ME

Foley-Baker Inc.

Portland’s Kotzschmar organ stands out as one of the most resilient of public organs, a foot soldier of front rank in the campaign of organ awareness. In the century between its 1912 dedication and its 2012 dismantling for renovation, Austin Opus 323 always played, often frequently. The original donor, publishing titan Cyrus H.K. Curtis, gave additional funds in 1927 for more stops and percussion. A municipal commission and city dollars established the position of municipal organist, with early prominent players including Will C. Macfarlane and Edwin H. Lemare.

The organ’s first decades were not without contention, particularly during the Depression. But, during a decade when many such instruments fell silent, Portland’s kept going, through pluck and the good spirit of the players. After the war, other challenges arose. A 1968 renovation, intent on increasing stage size while reducing seating, forced an unfortunate relocation of the instrument. In the process, two original 32′ stops, the Bombarde and Magnaton, were lost, although an Austin half-length 32′ was installed in compensation.

A second renovation of the auditorium in 1995 further diminished room reverberation and seating (now at 1,900), and once again remodeled the stage. This effort required complete removal of the Austin; it was reinstalled in 1997 with minimal repairs. Over the next years, curator David Wallace continued to address leakage and stabilize the installation, in the process installing a 32′ Magnaton from the 1910 Austin at Smith College and a 32′ Bombarde of his own manufacture using the original 1912 32′ Bombarde boot assemblies that had survived. Austin returned to provide a new, five-manual console in 2000, a bit of re-actioning in 2003, and a few tonal changes.

FOKO

Meanwhile, in 1981, in a series of budget cuts, the municipal organist position was eliminated. In response, a nonprofit group formed to maintain the position and the organ series. Friends of the Kotzschmar Organ (FOKO) has grown into a model organization of its type, supporting the organist and a full-time director, who, with volunteer and board assistance, runs the series (between 16 and 18 concerts annually), coordinates artists and publicity, publishes a newsletter, and maintains a website. By 2005, the organ had come almost a full century with occasional repairs

but never any systematic overhaul. Many on the FOKO board believed the instrument had arrived at a solid place, with more repairs being undertaken as funding came in. And, under the right hands, the instrument certainly continued to give an illusion of virility, particularly with such an able ambassador, municipal organist Ray Cornils.

NECN Video: Restoration of the Kotzschmar Organ

A Turning Point

Continued dissatisfaction with the 32′ situation led to a survey by reed voicers David A.J. Broome and his son Christopher in January 2006. Their visit turned out to be a critical turning point in how the organ and its needs were addressed. While the Broomes made recommendations about the various 32′ voices, they were unwilling to work on the organ as they found it. This assessment drew fresh attention to the fact that the organ’s condition was not what it should be. The situation was one not of poor workmanship or lack of dedication from FOKO, but of a gulf between a patch-repaired organ seen against the growing number of superbly restored and renovated pre-WWII American organs dotting the national scene.

One board member, organ technician John Bishop, saw a way to resolve the dichotomy. In September 2007, he organized a symposium, drawing together respected players and restorers specializing in instruments of the era. A comprehensive survey followed, in January 2008, that I undertook together with longtime Austin organbuilder Victor Hoyt. Our report built a detailed picture of the organ’s condition and developed a suggested workscope and budget.

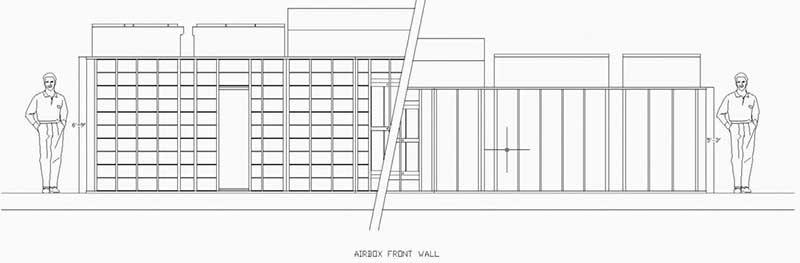

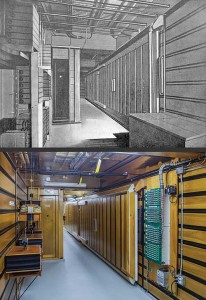

The crux of the matter came in the condition of the Universal Air Chest—that giant box filled with wind, inside of which anyone can walk, while the organ is functioning, to observe the action in operation and make adjustments. The Air Chest is both the trademark and the bedrock of any Austin. While instruments like this have a reputation for muscular invincibility, in truth, any instability in the Air Chest’s structural soundness or wind system will cause the tone and action to suffer. And in a very real sense, the Air Chest is the organ. Typical of Austins from this period, every pipe sat upon the Air Chest, from top C of the Fifteenth to 32′ C of the Bourdon and Bombarde. Given the organ’s two physical disruptions, the Air Chest had been severely compromised. Had it been in original shape, a renovation might have been easier. Making the windchest anew meant complete dismantling, and with it the inevitable but expensive desirability of a thorough renovation.

(drawing by Jim Bennett, Foley-Baker Inc. shop foreman)

Gaining Momentum

To its eternal credit, the FOKO board swallowed the hard news and got to work. The budgetary guidelines we had supplied were placed within the context of a new $4 million fundraising objective—one that sought not only to fund a project but also to endow maintenance, salaries, and programming. The board built further bridges with city officials and explored every avenue for public and private funding. The city council was sufficiently won over that it unanimously approved a $1.5 million bond dedicating $1.25 million match toward the renovation effort, to be satisfied by a $2 surcharge for all tickets to Merrill Auditorium events. After soliciting proposals, FOKO selected Foley-Baker Inc. (FBI) to handle the job. While the firm had never renovated a large Austin, FBI had an enviable record with other large organs, and clearly possessed the skill and experience to get the job done without compromise. Moreover, the company had worked with challenging schedules before, a necessary skill for Maine’s premier arts venue.

In many ways, Foley-Baker treated the job as a new organ project. They began by drawing out the entire organ in CAD, and from there planned the construction of the new Air Chest to include two new original-sized 12′ expansion board regulators. This approach allowed the air box to be built in advance of the organ’s removal and to original Austin specifications gathered from onsite reconnaissance work with similar period Austins. (Indeed, this may be the only Austin Universal Air Chest to be built outside of Austin’s factory.) With that opportunity came the chance to reconsider the organ’s layout. While the manual departments remained as they were, the 32′ Bourdon and new 32′ Open Wood were placed on unit chests against the solid concrete stage walls, for maximum reflectivity. All nontonal percussions were removed from an already crowded upper-level percussion chamber (added in 1927) and made unenclosed, in a location more normally encountered on theater organs. And, knowing that thousands of visitors would be filtering through the instrument, FOKO member David Wallace provided a handsome walkway and stairs, allowing Air Chest tours to safely include a close-up look at freshly restored manual and pedal pipes, without fear or favor.

large regulators and control systems on the right

Tonal Work

While the terms “renovation” and “restoration” are often used interchangeably, they mean considerably different things as applied to old organs. In a restoration, as little as possible is changed, not even the console. Thus, renovation is the correct term for this project. The organ’s 1912, 1918, and 1927 consoles are long gone, the room itself is twice changed, the facade slightly modified. As the organ’s tone had evolved somewhat since 1927, the opportunity was taken to effect a few more tonal changes while putting every pipe on a fresh tonal footing—in particular, ensuring a clear treble. When Austin refurbished the Great mechanism in 2003, the workers were able to compress the chest sufficiently to include a four-rank Mixture. In FBI’s project, that stop has been replaced with a new five-rank register more in keeping with the organ’s tonal language. The Swell 16′ Quintaten has made way for a new 4′ Octave, while the Vox Humana has been relocated to its own windchest (itself a vintage Austin “Vox Box” with built-in tremulant) and a new 4′ Clarion installed in that position, built by A.R. Schopp’s Sons and voiced by Christopher Broome.

Of the three original 32′ registers, by 2012 only the Bourdon remained, badly cracked and unhappy. FBI spline-repaired these pipes, relocated them against the rear wall, cut the mouths higher and drove them harder for more impact. The organ’s original 32′ Magnaton remains a mystery; Austin applied the term variously to reeds and diaphones, and the record offers no clue to which sort this organ had. A 1910 Magnaton from the Austin at Smith College had been installed several years ago, pipes of diaphone construction that didn’t work very well and wouldn’t come to pitch. Unwilling to discard these fascinating pipes, FOKO requested that they be stored. In their place has been installed a new 32′ Open Wood, built by Organ Supply Industries using Haskell construction. Like the Bourdon, these pipes are mostly located against the rear wall, for maximum reflection. Finally, a heavy zinc Pedal reed extension, built by A.R. Schopp’s Sons and voiced by Christopher Broome, restores a tonal element not heard in almost 50 years—a solid and impressive 32′ and 16′ reed bass more usually associated with wooden resonators. Apart from that, the organ’s pipes have been intensely reconditioned: tidying up slots, fitting scroll-tuned pipes with slide tuners, and checking all pipes for structural soundness and good speech.

car horn, train whistle, fire gong, and doorbell—used for silent movies)

Reeds

In dealing with reed stops, for many years, FBI has partnered with Broome & Co. LLC, for both reconditioning and new work. This organ had 16 existing reeds to be considered, and, as with the rest of the instrument, decline was greater than that typically encountered. Reeds were reconditioned in the manner developed by the late David A.J. Broome: complete cleaning of all parts, installing new tuning wires and new metal inserts and slots, and checking tongues and curvature for consistency. Although Austin always employed brass reed wedges, many in this organ were pushed in flush with the block. Thus, new wedges were introduced, some slightly larger in the treble. The high-pressure Tuba Magna, built more along Trumpet lines, had been radically revoiced in the 1960s. It was restored to a more conservative Tuba sound.

The 2000 Austin console was stripped to bare bones for remedial structural work, and the many different solid-state controls systems unified into a new Artisan Classic unit. With advice from Peter Conte, certain features have been incorporated to aid in complex playing, including settable Pedal Divide and All Pistons Next. In the organ’s mechanical refurbishment, Austin Organs Inc. collaborated in many ways, principally in providing factory-authorized replacement actions.

The organ has a mixture of tremolo types. Austin’s customary revolving fan is found in the lower Swell, Orchestral, and Solo departments. The Echo and Antiphonal were always fitted with valve tremulants, and now refurbished, they continue to provide the more traditional (i.e., non-Austinian) vibrato, as does the 1927 portion of the Swell.

Gala Rededication

At the point when funding was finally secured, too little time was available to renovate the organ for the organ’s centenary. Instead, FOKO turned that occasion into the renovation kickoff. In August 2012, following a grand final concert, the FBI crew started removing the facade pipes just minutes after the final notes. Determined not to let the organ slip from public awareness, FOKO developed an intensive education and publicity initiative. While people might not hear the organ for two summers, they couldn’t fail to know that FOKO and the organ were very much still in the picture. In summer 2013, FBI returned all the mechanism. This past summer saw installation of all the pipes, with tonal finishing and final tuning in August and early September.

On September 27, members of the sold-out audience took their seats to see a stage covered in scrim. On the stroke of 7:35 P.M., a row of white-hard-hatted workers became apparent through the black. On the count of three, the scrim dropped to a beautifully restored facade, the rebuilt five-manual console, a brass troupe, municipal organist Ray Cornils, and guest organist Peter Richard Conte. A commissioned work by Carson Cooman, creatively depicting the instrument awakening from its 24-month slumber, opened the program, which continued on to more familiar fare, both serious and light. Showers of applause greeted the musicians, particularly for FOKO, Cornils, and the FBI crew.

Organist Ray Cornils plays Toccata from Suite Gothique on the Kotzschmar Organ

In strict terms, the municipal organ is a relic of a bygone age, when it was rare to hear music made on the grand scale outside of the largest cities. Such organs allowed a single person to substitute for many, and gave satisfaction to a public hungry for music. Today, music infiltrates our lives in a manner unthinkable a century ago, as formerly hushed bank and elevator interiors are now equally awash in banal stylings. Maintaining the interest, funding, and audience for any public organ in the 21st century is a heroic feat. Portland remains a gold-star example of how to do it.

For the stoplist and other technical details, visit Foko.org.