Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School Chapel

Hong Kong

C.B. Fisk Inc. • Gloucester, MA

By Elizabeth Hung Wong

The pipe organ is not a familiar musical instrument to most people in Hong Kong. The few pipe organs that were installed there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries did not survive. The blame was mostly put on high humidity. An English gentleman did open an organbuilding shop in Hong Kong in the early 20th century. A few of his instruments are still standing in churches, but they are not currently playable. One of them made its way to the Philippines and was recently completely restored. Several small-to-medium-sized pipe organs built by European builders were installed in area churches in the mid-20th century, but they have not garnered much attention.

It is the general belief that two things—space limitations and the weather—make Hong Kong unsuitable for pipe organs. There are many “upstairs” churches, meaning that the church is located on one or two levels of a high-rise building. Hence the limitation on height and space. High humidity (over 90%, sometimes 100%!) often lasts for several months of the year. The frequent switching on and off of air conditioners, because of the high energy cost, causes fluctuation in humidity levels within a short span of time. Pipe organs, everybody knows, do not like this. Owners of instruments in Hong Kong tend to be overly protective; so very few people are allowed to play or even touch them. Organs are not regularly maintained because of the distant locations of the builders. As a result, many churches have turned to electronics as substitutes.

With the opening of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre and the Academy for Performing Arts in the late 1980s, two large European built organs came to the city.These concert hall instruments have brought more awareness of the pipe organ to the general public. More opportunities were created. More students studied the organ at the university level. Most of them have gone abroad for more advanced training, but not too many were willing to return to Hong Kong. There were few opportunities waiting for them.

After my undergraduate studies in economics at the University of Toronto, I returned to Hong Kong and worked as a merchant banker. I learned to play on an electronic instrument, but I fell in love with the organ. I started attending church-music courses, and the more I learned, the more inadequate I felt. Finally, I gave up my business career and enrolled at Northwestern University to study with Wolfgang Rübsam, then professor of sacred music and organ. During this time, I had the opportunity to play on many different types of organs in America and in Europe—both historic and new—and I learned a great deal from them.

When I discovered how the old organs in Europe have withstood the harsh, dry, and cold weather over the centuries, I thought that, with modern technology, organ builders in the 21st century ought to be able to find a solution to this age-old “misunderstanding” for Hong Kong. Pipe organs can be found in other places with a tropical climate; they should also be successful in Hong Kong. I started seeking advice from experts and began planting ideas with schools, universities, and churches. Steven Dieck of C.B. Fisk and I met at the AGO National Convention in Boston two years ago. When he told me that he was interested in visiting Hong Kong, I was both excited and worried. I was happy that he wanted to pay a visit. However, I did not know what I could show him or who else he should meet.

Shortly before Steve arrived, an Anglican priest asked to see me. She has been a very supportive friend. Initially, I thought that it was another one of our friendly visits. Little did I know that she had something exciting in mind. She is the supervisor of Sheng Kung Hui (the Chinese translation of Anglican Church) Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School. The school had just converted an old classroom into a small chapel, thanks to the handsome donation from a faithful parishioner. With lovely stained glass windows and nice furniture, an organ would be appropriate to complete the chapel. It was very timely, I thought. Steve could give me some “friendly” advice. I never would have imagined chat it would become the beginning of the design of Opus 149.

Trying to decide what kind of an organ to put into this modest-sized chapel was not easy. It could only be the size of a practice organ. However, it would also need to serve as a teaching studio instrument. This was the kind of opportunity that does not come around very often. It took the Fisk team some time to come up with a proposal, but their concept is very creative and inspiring. The organ contains only seven ranks of pipes, but it can play so much repertoire—even the French Romantic. It is a fine instrument, and many will play it regularly. A pipe organ needs to be played, as this is the best way to keep it problem-free. Because of this, I made a promise to the people of Fisk that Opus 149 would be played often.

In recent years, several young organists who have received a high level of education overseas have returned to Hong Kong. A few of us have come together and started the Hong Kong Chapter of the AGO. It was chartered at the 2014 Boston convention. We want to bring the wonderful knowledge of organ playing and the instrument that we love to our homeland. In the process of forming the chapter, we have discovered many skilled but “hidden” talents around. There are others who are lovers of organ and choral music but who do not know where to find access. Together, we are working toward bringing more awareness of the pipe organ and its music to Hong Kong, and we are committed to finding ways of acquiring more fine instruments. This is our dream and our mission. Soli Deo Gloria!

Elizabeth Hung Wong is chapel organist at the Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School in Hong Kong and dean of the Hong Kong AGO Chapter.

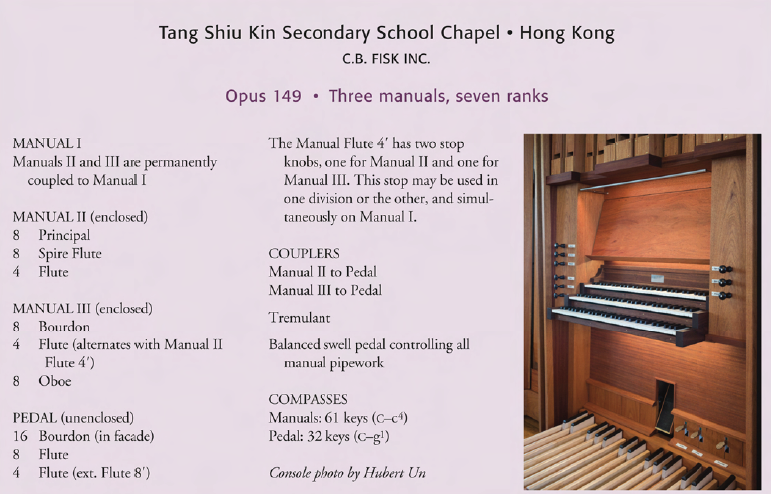

From the organbuilder

At the Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School Chapel in Hong Kong, our aim was to create a compact, responsive, and versatile mechanical-action instrument with a unique appearance—something with a 21st-century look that would be both practical and instructive for students of the organ. The casework, built of mahogany in order to survive the extremes of a tropical climate, is quite spare. It nevertheless has some distinctive features, including angled double-posts that lean forward on either side of the console, a single broad canopy like roof, and decorative end panels.

As with all Fisk organs, a physical scale model was created to facilitate case design and shaping of pipe arrays. This method, handed down to us Fisk, has proven to be the single most important tool for a complex design process that includes the collaborative ideas of the organbuilders, musicians, clients, and other design professionals involved with each project. As a result, Opus 149 has a recognizable Fisk sculptural signature with a unique personality. It is part of a contemporary design evolution building upon Fisk’s Opus 132 in Kobe, Japan, and Opus 146 in Glendale, Ohio, which explored the use of angled posts, wood Key action installation pipe arrays, and dramatic roof overhangs.

Opus 149’s closest relatives in this diverse genre of small studio, chapel, or residential music room organs are the similarly conceived practice organs at Rice University (Opus 118/3), built in 1999 by Fisk in collaboration with Schreiner Pipe Organs Ltd., of Schenectady, New York, and at the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University (Opus 142), completed in 2012. These instruments have three manuals, with Manual I serving as a coupling manual. Any stop drawn on either Manual II or Manual Ill automatically appears on Manual I. This concept allows for surprising registrational flexibility. Furthermore, the three manuals, which simulate a terraced coupling arrangement, are important for playing 19th- and 20th-century repertoire.

We had been thoroughly warned about the extremely high but occasionally fluctuating humidity in Hong Kong. In order to minimize its effects on the organ’s key and stop actions, the console and action frames were built entirely of aluminum, and carbon fiber trackers were used throughout.

All manual pipework stands on a common windchest and is under expression in a single large swell box. A delightful variety of timbres is available to the organist. At 8′ pitch, on Manual II one finds a principal and a tapered flute (a quasi string), and on Manual Ill a stopped flute and a reed. At 4′ pitch there is an open cylindrical flute, the one stop that is shared between Manuals II and Ill on an alternating basis. The Pedal division pipework is outside of the expression box.

The mahogany Bourdon 16′ pipes form the entirety of the facade, while the unified Flutes 8′ and 4′ are placed just behind the facade or behind the pierced end panels. All pipes, both metal and wood, were crafted in our Gloucester workshop, the metal pipes from lead and tin alloys cast by our pipemakers according to age-old techniques.

Wood pipes in organ facades can often have an awkward, monolithic appearance, but here they are playfully arranged on irregular corner plinths that accentuate the diversity of their dimensions as well as their sculptural qualities. For the center grouping, there is a similar playfulness in which the backs of the pipes are set in a straight line so that the varying scales and heights with the natural pipe lengths create a variegated landscape.

Opus 149’s visual and tonal designs are essentially of a piece. As befits an unusual but versatile tonal concept of a three-manual,seven-voice instrument and pipework that is nearly all under expression, the case design is intended to delight but never overwhelm the viewer. If,as we hope, more are commissioned in the future, we wish for this instrument to be an effective but soft-spoken ambassador for design integrity and fine music making.

Charles L. Nazarian, Designer