Setauket Presbyterian Church

Setauket, New York

Glück Pipe Organs

New York, New York

Stoplist

By Sebastian M. Glück

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Setauket Presbyterian Church owned an ailing pipe organ to which artificially generated voices had been added. It had served with a degree of adequacy but extended no consideration to the performance of organ literature. When designing the new instrument with consultant David Enlow, we agreed that if it could suit the noble repertoire of the past, it would be a fine church organ as well. No instrument can be loyal to every culture and era, yet we were adamant that specific tone colors should be placed in the correct divisions at the proper pitches, to honor as closely as possible the intentions of composers. To achieve this in a two-manual, all-pipe instrument, some amount of duplexing and extension would expand the specification.

For the first time in my career, I placed the entirety of the organ’s resources under the control of expression enclosures, in part because there is no reverberation in the very small, carpeted meetinghouse. The flexible timber building absorbs lower frequencies, so the organ includes ample harmonically complex tone at 16′, 8′, and 4′ pitch in addition to the colorful mutations and traditional chorus-work.

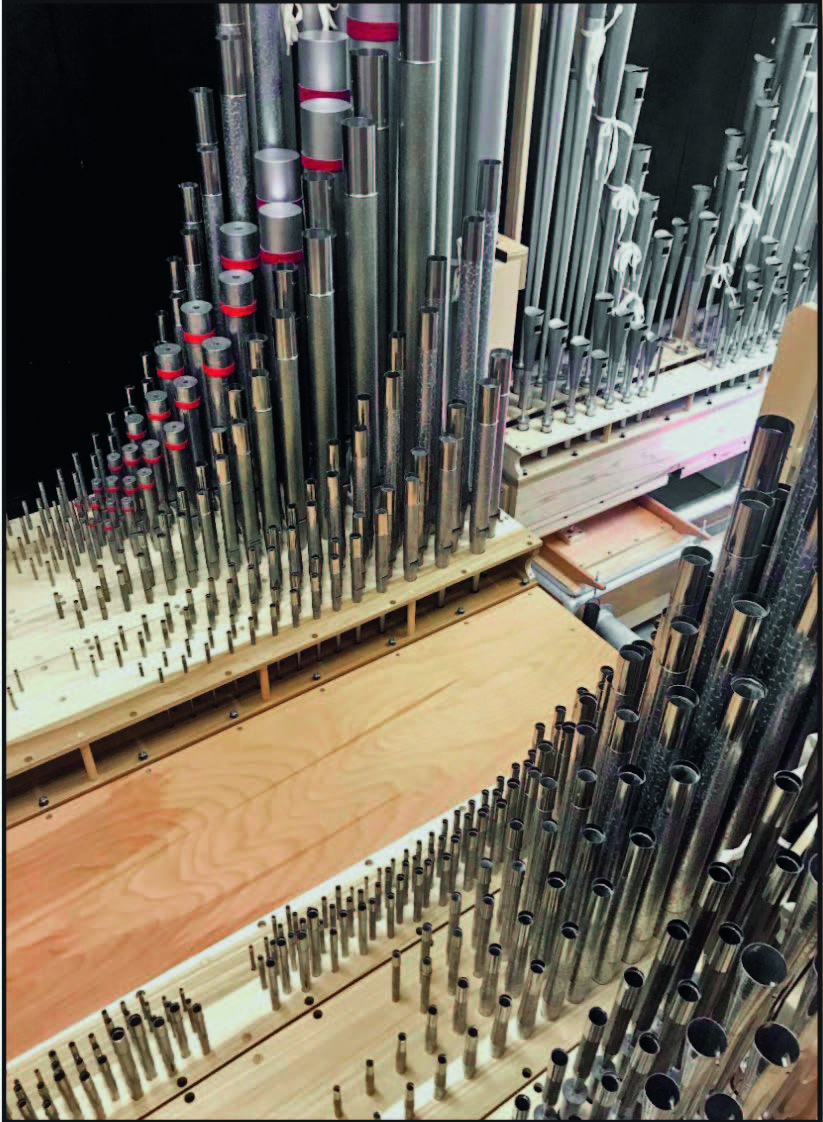

The Musical Blueprint

The key ingredients for the manual divisions are a pair of contrasting principal choruses, an 8′ Flûte Harmonique for the Great, a string and its undulant, the components of a Cornet, and the three primary colors of reed tone: Trumpet, Oboe, and Clarinet. The structural varieties of the flutes include open cylindrical, open tapered, open harmonic (overblowing), stopped wood, and capped metal with internal chimneys. They are voiced and finished within a bounded range of amplitude for the sake of blend.

The Great principal chorus is furnished with the Fourniture IV–V, which includes a second 8′ Principal to add warmth and body to the right hand. The 8′ Flûte Harmonique is scaled and voiced with characteristic treble ascendancy, and the Swell strings are made available to generate the fonds de huit pieds and to accompany the Swell’s solo voices when needed.

The Swell 8′ Principal lends body to the full ensemble when the organ is played with orchestra, and the 4′ Principal is the pivot point and tuning reference for that division, one of two 4′ stops that can be selected to change the vowel of the full Cornet. The Swell Mixture is designed so that it can weld to the Pedal principals when coupled down. With all shutters open, the Swell serves as an appropriately balanced second manual for Baroque and Classical literature.

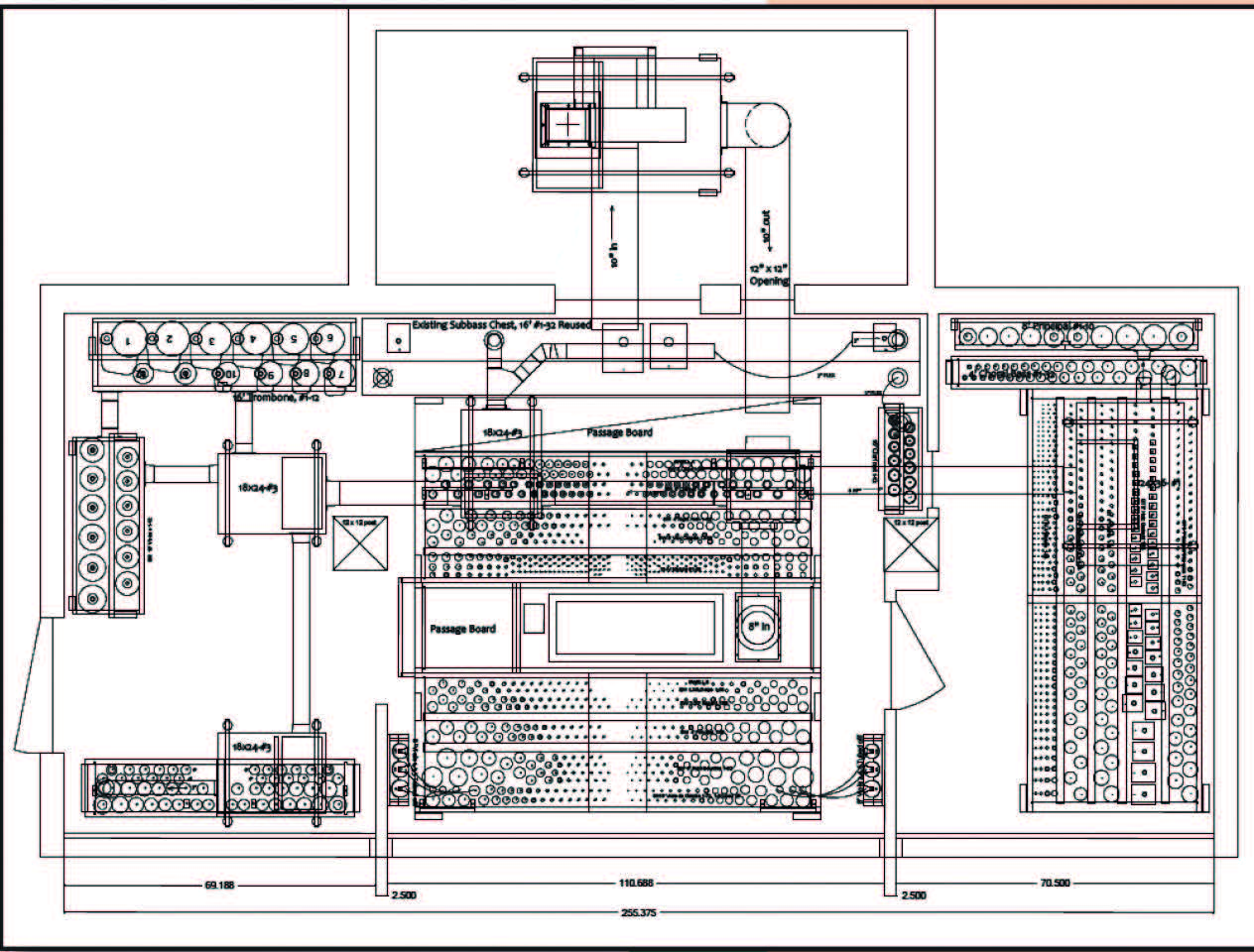

I could not provide full independence to the Pedal division, so I had to ensure that its musical line could be heard moving against the manual textures. The chamber plan for Opus 24 reveals the structural obstacles that had to be skirted while granting safe and facile access. The Pedal 8′ Principal and 4′ Choral Bass reside within the Great expression enclosure, with the remainder of the Pedal resources enclosed with the Swell. The dedicated 16′ Sub Bass exhibits a characteristic of many 16′ stopped wood ranks in small, acoustically dead rooms: if the listener steps in one direction or another, or turns their head, a note can switch from booming to absent. Instead of the ubiquitous and useless 16′ extension of a manual stopped flute, the Pedal 16′ Violone provides clean pitch definition and consistent acoustical reinforcement anywhere in the room and is far more interesting to the musical ear.

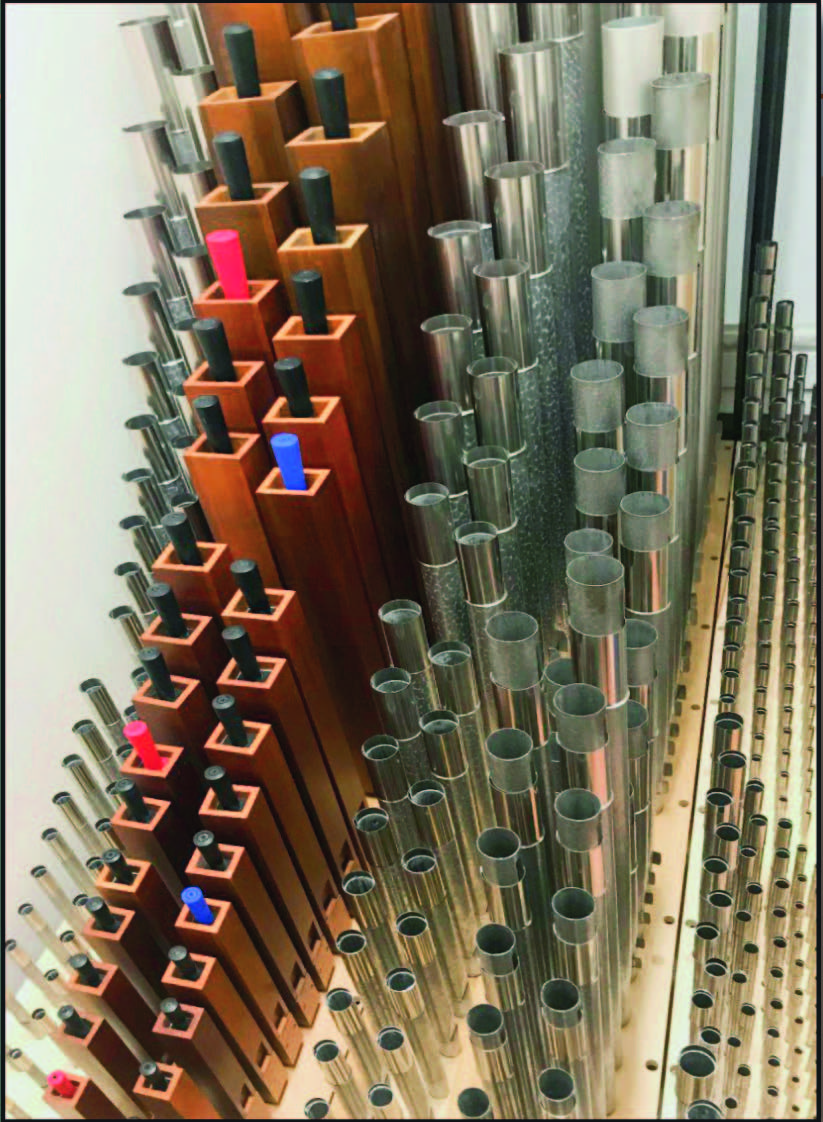

The Reeds

In a small instrument with only three reed ranks, it is a challenge to design a single Trumpet, as it cannot serve more than one master. If powerful enough to stand as the Great 8′ Trumpet, it is likely too forceful for its expected roles in the Swell. Conversely, if designed as a normal Swell stop, it may prove insufficient when drawn with the Great chorus, unsuitable for some solo functions, and too weak for the Pedal, even if it grows dramatically as it descends into the 16′ octave, as it would in a French organ. Knowing that French reeds can be quite unpleasant in acoustically dead American churches, I chose to favor the Great and Pedal with a round and warm English quasi-Tromba that makes the transition down to a rolling 16′ Trombone, which sits majestically under the full organ.

The Swell 8′ Oboe features English shallots with capped and scrolled resonators. If the Trumpet proves too loud for a particular registration, the tone of this Oboe can be modified by one or more of the division’s flue stops, including the mutations.

The cylindrical half-length reed posed a conundrum: What should it be, and what should it do, and where should it reside? Any version of the American Krummhorn of a half century ago was dismissed from the outset. A woody, round Clarinet with a bit of a bright “edge” would address anything from Clarinet solos in English choral anthems to dialogues in French Baroque suites. The extension down to a 16′ Basset Horn provides rich timbre with a fully developed fundamental, delivering the desirable growl and harmonic complexity of “full Swell.” The sticking point is that it plays at 8′ pitch from the Great and 16′ from the Swell. Were the Great unenclosed, the 8′ Clarinet under expression would have been a forthright bonus, but since the Setauket organ is entirely enclosed, the Clarinet is seemingly in the “wrong” enclosure. It is assigned to the Great to chat with the jeu de tierce in the Swell, and the rank plays in the Pedal as a secondary unison reed and as a Cantus Firmus stop for chorale settings.

The Mixtures

Rather than succumbing to the tiresomely recycled centennial fad for the deprecation of mixtures, the Setauket mixture compositions are not acute in their pitch bases, and they favor unisons over fifths to achieve a clarity that does not force the reeds toward brash caricature to make their contribution to the ensemble. The mixtures are polite but by no means weak, and they weld to the ensemble rather than stand apart from it. The effectiveness of mixtures is contingent upon their position, harmonic composition, scaling, mouth proportions, voicing methods, and tonal finishing. From time to time, errant theorists have campaigned aggressively to extirpate mixtures from the art of organbuilding, yet these stops inevitably return to the craft because they are essential to the organ’s origin and design.

A Case of Deception

Setauket’s 1812 landmarked meetinghouse was not conceived for a pipe organ, and the congregation, founded in 1660, did not install its first organ until 1919. The altered 1968 instrument incorporated pipes and speaker cabinets packed into a chamber, and the organ could not be maintained effectively. There were no organ pipes to be seen, the works concealed by a metal mesh screen that covered an enormous black void.

My duty was to create an architectural solution half as tall as its width, and I arrived at a small facade centered upon a visually neutral backdrop. Initial designs were based upon Georgian chamber organs, but as I spent more time in the building, I saw that the space demanded a more restrained treatment, a contemporary interpretation of organ cases built in New York during the second quarter of the 19th century. It is a restfully proportioned quintipartite mahogany facade, devoid of carvings, with burnished front pipes that extend to the cornice.

Paradoxically, this visual treatment is an entirely deceptive set piece, yet it respectfully complements the historic interior. The wall of painted joinery incorporates acoustically transparent grille cloth in place of solid panels, and the facade pipes do not speak, on account of the enclosure of the entire organ. Whereas once there was no visual indication that an organ existed, there is now a correlation between what the eye sees and the ear hears, despite the grand body of tone that seems to issue from a chamber organ.

The Next Century

A century after organ music was introduced into the life of Setauket Presbyterian Church, the congregation’s third organ moves beyond the utilitarian support of hymnody. It is a carefully designed musical instrument developed from a thoughtful investigation of the historic church organs for which composers wrote their music while they performed their duties as church musicians. We must relieve ourselves of the delusion that “repertoire doesn’t matter” and that the organ of the great literature bears no relationship to the organ of the church service. They have, for centuries, been one and the same.

Sebastian M. Glück is artistic and tonal director of Glück Pipe Organs in New York City. He is also an active lecturer, author, and consultant in the field.