The Liturgical-Symphonic Organ, or A Tale of Two Austins

St. John Vianney Catholic Church

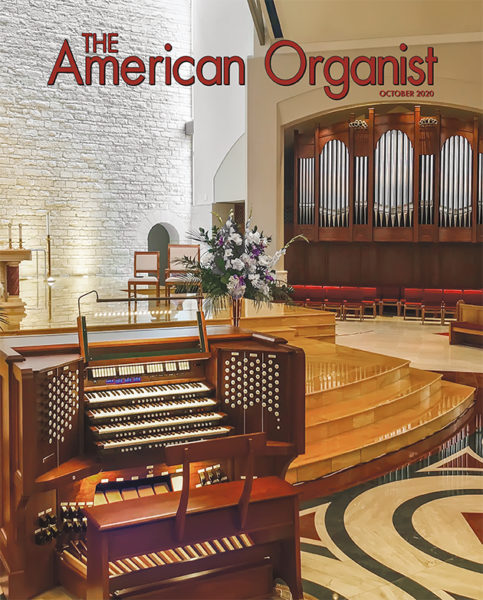

Houston, Texas • Austin Opus 2798

Connelly Chapel, DeSales University

Center Valley, Pennsylvania • Austin Opus 2800

By Michael B. Fazio

Background

Many of us remember the American Classic tonal concept as espoused by Aeolian-Skinner and others. It was born of the Orgelbewegung (also called the Organ Reform Movement) that began in Europe during the 1920s. Coming across the pond, it was tempered by American sentiments. Each major builder had their own take on the idea; while some considered it as simply a marketing scheme, others assumed the mantle proposed by the movement with unwavering devotion. G. Donald Harrison of Aeolian-Skinner conceived the American Classic organ as a single instrument that could convincingly play music of all styles and eras with equal facility. Meanwhile, in Hartford, Connecticut, Austin Organs followed its own slow and carefully measured path; Austin was never an early adopter.

Robert Pier Elliot, a director of the Austin Company at the start of the 20th century, was instrumental in bringing an Englishman to the company in 1903. This individual, Robert Hope-Jones (1859–1914), installed as vice president, would have an extremely brief tenure in Hartford, but would become known as a controversial character in the organ world in short order. He eventually worked for the Wurlitzer Company, and he is rightly credited with the invention of the theater organ. His guiding principle was that the organ would encompass the instruments of the orchestra and, in fact, could emulate and thus become a complete orchestra unto itself. To this day, many of the orchestral or color stops we find in our instruments echo his vision in this respect. Austin published a pamphlet in 1911 exemplifying their version of the “unit orchestra” for hotels, theaters, and various public venues. Orgelbewegung followers later vilified these concepts in both tonal and mechanical aspects.

In the early 1930s, James Jamison (1905–57) was considered Austin Organ Company’s de facto tonal director, as this role had not been part of Austin’s operation to date. While he never maintained an office at the factory in Hartford, he lived in California, designing instruments in diaspora. Jamison had certain ideas with respect to tonal design; they are embodied in his book, Organ Design and Appraisal, published in 1959. Many Austin installations, from Connecticut to Hawaii, are examples of his designs. The most significant impact he had on Austin Organs was his work involving the scaling of the diapason chorus. It was developed from specifications found in The Art of Organ-Building by George Ashdown Audsley, published in 1905. Within the pages of our ancient office copy, one can find notes in the margins by Jamison and Basil Austin. The result was a “new” chorus, and it was debuted in the Austin showroom in 1933 to “critical acclaim of local and visiting organists.”

In 1954, Richard Piper (1904–78) became Austin’s first resident tonal director. Jamison was still in California, selling and designing organs, often different in approach, yet similar in result. David Broome (1932–2013), also an émigré from the U.K., arrived at Austin in 1959, working primarily as a reed voicer. Early on, he began working with Piper, whom he had known in England. Piper retired in 1978, and Broome continued the same basic trajectory, maintaining full confidence in the American Classic ideal.

In 2005, after 112 years of family proprietorship, the current owners purchased the Austin company. Analyzing current trends, we came to the conclusion that the organ tonal pendulum was swinging yet again. The bob was pointing back toward an earlier time, and we were happy about that. We have always been fond of signature orchestral voices such as the French Horn, Tuba, and Cor Anglais, not to mention big flutes and spicy strings; so we welcomed the opportunity to build in this style. The question on our lips was “What are we building?” The answer became clear: It was a tempered amalgamation of the best of the American Classic virtues, integrating the most useful (given space and budget limitations) orchestral/symphonic voices and associated scaling requirements. Perhaps in this instant, Austin was an early adopter of a new concept? The real question was “How can we make this tonal scheme viable for the service of the church?”

The senior staff at Austin has several veteran and current church organists; four of us have served at Roman Catholic and Episcopal cathedrals. From that background, we felt as though we had a strong grasp on what would prove useful for regular corporate worship, choral accompaniment, and performance of literature in the liturgical setting. Our critical focus was on the desire to get it right and not chance experimenting with a church’s trust.

Renovation projects over the past decade have involved several vintage Austins. This is always an emotionally rewarding venture for us. Instruments from the 1960s are often thin and somewhat lacking in character. In these cases, rescaling the diapason choruses, including some colorful reeds and flutes, gently increasing wind pressures, and general voicing yield exceptional results. Instruments from the early 20th century often need more clarity and tonal cohesion. One instrument in particular was Austin Opus 1702, built in 1930 for Old St. Mary’s Church in Cincinnati. In 2012, we embarked on a complete mechanical and tonal reconstruction. One interesting stop, a somewhat tired set of pipes marked 8’ Bassoon, caught my attention, because we often think of a Bassoon as a 16’ stop. It carried the opus number of the long-gone Austin installed in the Cincinnati Music Hall: Opus 1109 (1919). In reviewing the details from that instrument’s construction, we found that the Bassoon was patterned after a stop of the same name from Opus 1010 in the Eastman School of Music auditorium. This organ, monstrous by theater organ standards at 134 ranks, was laid out by Harold Gleason according to concepts as promulgated by Audsley. The orchestral element was strong, but as a balance, it also had a plethora of upperwork. The Bassoon was unique. I asked our pipemaker if he had ever heard of one while we were examining the pipes from Cincinnati. He told me that we had some patterns in the basement used for small trumpets in the 1970s that might work. Sure enough, those old patterns were engraved with their first use—Opus 1010! We have built three of these 8’ Bassoons since.

Opus 2798

An exceptional opportunity to build an instrument in this expansive new style presented itself at St. John Vianney Catholic Church in Houston. The process began with a phone call from Clayton Roberts, the church’s principal organist. It was clear from the outset what kind of instrument he wanted to build, and Austin was up to the challenge! The manual divisions of the organ would be enclosed; in fact, we discussed the possibility of building a double enclosure (two sets of shades in front of Great, Swell, and Choir organs) from the start. One set of louvers would serve as master expression (a single pedal opening all three primary divisions). The secondary set of shades would be controlled by individual swell pedals for each department, with stop controls to separate the primary shades also. Also, a master All Swells to Swell control would be available. The Solo division (installed in a chamber to the right of the main organ) would have a single set of shades operated by a dedicated pedal.

While each division has a specification typical of what one might expect in a liturgical instrument, there are stops that are unique to symphonic design. In the Great, along with a plethora of foundation stops, we see an 8’ Bassoon, similar to the pipes found in Opus 1010, except that this stop is capped and voiced rather sweetly, and so it carries the name Cor d’Amour 8’. The Swell reeds are effectively symphonic and carry broad tone. Notable also is the Vox Humana, one of two in this instrument. The Choir boasts a grand Trumpet, brighter than the Swell reeds, but of a slightly demure dynamic. The Solo speaks clearly from the right chamber, of bold character but not overbearing for the space. The chamade is built to our Waldhorn specification—commanding, but not bombastic. The four-manual drawknob console on an enclosed dolly is built to Austin’s standard, playing through a Solid State Organ Systems control system.

Opus 2800

In keeping with DeSales University’s Roman Catholic–Salesian tradition, Connelly Chapel sits on the top of the hill, keeping watchful eye over the entire campus. The worship space is intimate but reverberant, as the room is shaped somewhat like the inverted hull of a massive schooner: tapered at each end, with ample belly in the middle. This curious pattern delivers an auditorium where one cannot find a bad seat for hearing either voice or organ clearly. That said, the architect did not plan space for an organ at either end of the chapel, but by clever repurposing of a small side chapel and the music library on the opposite side of the chancel, we were able to create space for the two enclosed divisions. The design parameters specified by Dennis Varley, director of liturgical music and creator of the new Catholic Liturgical Music Scholars program, called for a modest three-manual specification. We proposed an exposed Great comprising a rich diapason chorus, and a Swell that delivers not only the essence of a classic English full Swell, but meets the requirements of adequate performance of the literature. The Choir/Orchestral organ fulfills some of the middle ground. Its ensemble will serve as a tertiary chorus of sorts, while it maintains many solo voices and colors required for symphonic rendition of transcriptions. Due to space limitations, much of the Pedal depends on the generosity of its neighbors. The three-manual drawknob console is movable, built on an Austin enclosed dolly system.

Summary

These two specifications are rather different in scope and size, yet similar in approach. Each boasts clear diapason choruses, a plethora of color stops, and stops with symphonic character. Yet each instrument delivers tonal clarity and appropriate strength in respective departments. Each specification can play a diverse range of literature while supporting congregational song and, perhaps most importantly, the ever-expanding needs of the liturgy.

Michael B. Fazio is president and tonal director of Austin Organs Inc. Website.