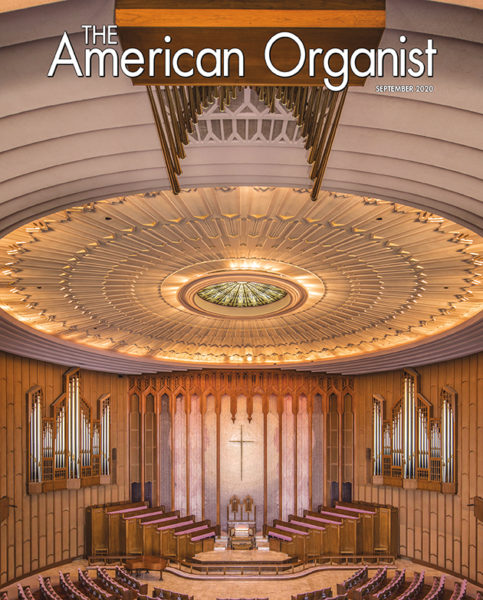

Boston Avenue United Methodist Church

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Foley-Baker Inc. • Tolland, Connecticut

By Mike Foley

We were working in Tulsa when I spotted a unique Art Deco building standing tall at the end of the city’s princely Boston Avenue. It looked like a small version of the Empire State Building. I was told it was Boston Avenue United Methodist Church, designed by a most talented local artist and teacher, Adah Robinson. It opened in 1929 and indeed was meant to look as strikingly strong and elegant as it does. The interior is very large, with meeting rooms and offices everywhere, including the senior pastor’s at the top of the tower. The focal point is the 1,358-seat sanctuary-in-the-round, accessed by a spectacular narthex. The entire place is an Art Deco paradise.

Kilgen was contracted to install the original four-manual, 51-rank organ in the four chambers located to the left and right of the choir pews. In traditional settings, this would be a typical arrangement, but the wide, theater-like sanctuary meant that chambers were considerably separated. Despite being hidden behind heavy plaster grilles, with its big scales and high pressures, the Kilgen’s sound was doubtless quite heavy. It all went away in 1961 when the church purchased Möller Opus 9580 (four manuals, 71 ranks). Nearly a knee-jerk reaction to the sound of the Kilgen, the Möller was well built but typical for the ’60s: low pressures, thin, and brilliant. In 1986, Möller returned to broaden the sound, and they added another 34 ranks. The work also saw half the chambers and their openings enlarged. The restrictive grilles were replaced with new facades, thereby allowing the larger specification as well as improved tonal egress. The added stops did indeed broaden the tonal palette, but the process left the chambers so stuffed that the layouts were a cacophony of pipes, chests, wind lines, and wires. Plain and simple, they looked like Grandma’s attic. Tuning access was difficult; service was in places impossible.

During a major project on the Austin at Tulsa’s First Presbyterian Church, their organist, Ron Pearson, introduced us to Susan and Joel Panciera, the music team at Boston Avenue, and Fred Elder, a much-informed and interested retired BAM organist. Shortly after, we began including the organ in our tuning rounds. This gave us a good opportunity to get familiar with both its strengths and weaknesses. In time, we were asked to present a plan to rebuild the instrument. This would be no small task.

There was no changing the chamber placements or improving the sanctuary’s dry acoustic. Something that could be tackled, however, was the chamber wall surfaces. Dating from the Kilgen’s time, instead of projecting sound out, these soft, wood walls absorbed and retained sound. Everything from bass to treble suffered. Even swell shade effectiveness was compromised. Therefore, right after we had removed the organ, the project started with the church’s contractor stiffening the walls and covering every surface with drywall, finished glass-smooth and painted gloss-white. It worked! Whispers within them became audible most anywhere in the sanctuary. For the first time in the church’s history, these chambers would properly project sound. Excitement grew.

Over the years, the organ had grown to an unwieldy 105 ranks, some of which were redundant stops and others of which, the organists admitted, were seldom used. We determined early on that the existing chambers were more suited for a smaller instrument. Our design therefore reduced the total count to 76 all-important ranks. Each was carefully specced—or if reused, selected—to achieve the best possible tonal cohesion: the two words that determine the tonal success of any instrument.

Mechanically, new slider chests replaced Möller’s leather-heavy pitmans. Simple schwimmer reservoirs saw over half of Möller’s 31 bellows go away, clearing the decks for new and proper layouts that made for a well-laid-out and serviceable organ. The annoying pitch drift that existed between divisions was tackled with all-new insulation behind the chamber walls and ceilings. Especially subject to drift were the many speaking facade pipes, as the temperatures outside the chambers were often different from those inside. Roomier chambers saw the facades become mute and their new replacement pipes installed inside, within their divisions. Voila! No more pitch drift.

The console was gutted to the shell. New manuals, pistons, jambs, and a proper lineup of drawknobs make for a most welcome and new level of comfort for the organist. Updating and reusing the recently installed Peterson relay system offered good savings. The console was refinished with new contrasting colors and a new adjustable-height bench.

The 1929, 15-horsepower Spencer blower was completely reconditioned and reused, as was the original static reservoir. Air lines were cleaned and flanges regasketed. The rebuilt instrument uses soldered, galvanized metal wind lines throughout.

Every piece of reused equipment was completely reconditioned. Every piece of leather was replaced. Every flue pipe was washed or cleaned, repaired as necessary, and revoiced on our voicing machines. Any cracks in wood pipes were spline-repaired. Reeds were all reconditioned by Broome & Company.

Regardless of how perfectly an organ looks and works, in the end, it all comes down to its sound. As always, I am proud to offer that our tonal director, Milovan Popovic, has once more worked his magic and come up with what is without question a most desirable outcome: a musical organ. It becomes obvious the moment organists try their hand. Most seem to feel the organ makes the most of whatever they play. This medium- to large-size instrument offers three principal choruses, three different sets of strings, and a good variety of flutes. The Solo reeds satisfy any melody, plus there are two 16–8–4 reed choruses that build ensembles to massive but musical climaxes. These are capped by the new high-pressure Tuba located in the Antiphonal chamber, masked by the now unused en chamade that was dangerously inaccessible. Thanks to those hard chambers, the organ’s bass purrs or roars. The room’s floor can actually be felt shaking. The Wurlitzer small-scale Diaphone sits always in the background, but instantly, albeit gently, projecting any 16′ pedal tone.

At FBI, we can build organs, but having opportunities like this to be a Monday-morning quarterback, finally fix the wrongs, and deliver a genuinely satisfying instrument is what we’re really all about. For the record, we selectively reused and revoiced 51 percent of the Möller pipes. The bottom-line cost for the project represented an approximate 21-percent savings over the cost of a like-kind new pipe organ. A dedication program will be planned for the future.

Mike Foley is president of Foley-Baker Inc. Website.

All photos (including cover): Miller Photography Inc.

Penny,

You can read all issues of TAO with your subscription. You will find them here: https://wp.agohq.org/current-issue/. Click on a cover below and when prompted, enter the same username and password that you use to log into ONCARD. If you have any problems, let me know.

Is this all we get to see of the online subscription, or am I missing something?