Calvary Presbyterian Church

Newburgh, New York

E.M. Skinner & Son Opus 512

Restoration by Foley-Baker Inc.

Tolland, Connecticut

Stoplist

E.M. Skinner & Son Opus 512 was installed at Calvary Presbyterian Church, Newburgh, New York, in the summer of 1937. It replaced the George Jardine & Son instrument that was installed new when the church opened in 1860. In those days, Newburgh was a bustling center for the manufacture of all sorts of goods. Situated halfway between Albany and New York City on the Hudson, it was the perfect riverfront hub for commerce, and there was no end in sight to its prosperity when the new organ was dedicated on December 4, 1937. A total of 1,000 people packed the church that day for the two recitals by none other than T. Tertius Noble, from New York City’s prominent St. Thomas Church. Noble and Skinner had great respect for each other. The former had more than tipped his hat toward Skinner when, a few years earlier, he’d recommended Skinner’s new firm for the construction of the organ at Washington National Cathedral.

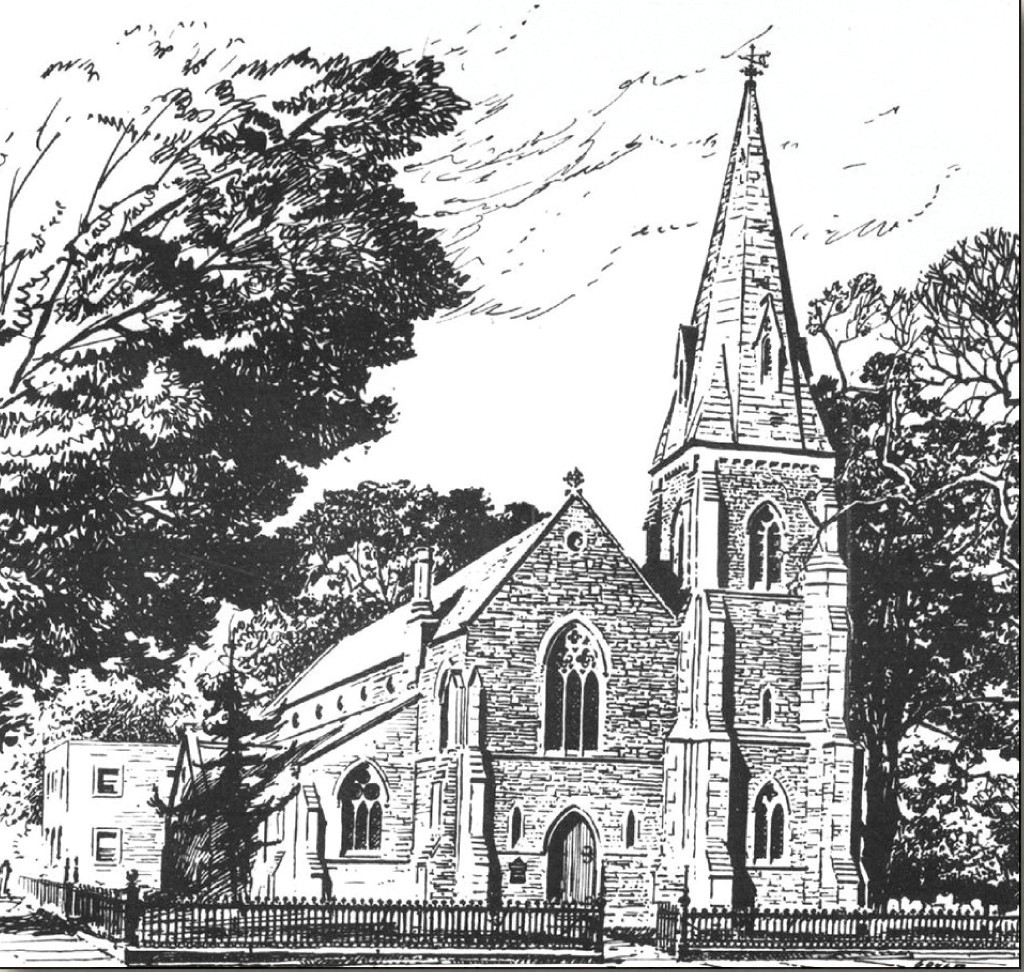

Calvary was the creation of the architect Frederick Clarke Withers. An Episcopalian Englishman, Withers had expected and hoped that his first American church contract would be with an Episcopal congregation. Regardless, when the Presbyterians at Newburgh stepped up, he was all ears. It was a fine commission for a 28-year-old architect, and in a town of good acclaim—the very town in which he was living. At the time, Calvary was named First Presbyterian Church (when the two congregations merged in 1945, First Presbyterian’s building was used, but Calvary’s name graced the structure). The organist then was Lydia Harris Hamlin. In time, Thomas Edison personally convinced the congregation to install electricity, making Calvary perhaps the first church in the state to have this incredible new feature.

Some may not know the backstory of the firm that built this organ. In 1919, despite great artistic success, Skinner’s Boston business was on the verge of financial crisis. All was saved when Arthur Hudson Marks, a retired businessman (and Skinner organ owner), stepped up and purchased primary ownership of the company. By 1927, Ernest had traveled to England, where he met and hired G. Donald Harrison, who became his direct assistant and voicer. Harrison’s tonal thinking leaned toward the thinner, trimmer sound of European organs, and his sound and name quickly generated enthusiasm in the American organ world—so much so that, by 1932, Marks had asked Skinner to step aside and let Harrison take over as the firm’s tonal director. Skinner was frustrated. Was he in fact falling from grace in the organ world, despite the signature sound that he had created? After all, the firm’s tremendous success had been because of him. Now this!

In fact, Skinner saw the end coming and had already prepared an escape plan by purchasing an unused organ factory in Methuen, Massachusetts. He remained a big name in the industry, and his followers kept a close eye on his new venture. Finally severed from Boston, E.M. Skinner & Son (Richmond) set up shop in Methuen, already with some nice contracts in hand. The largest of these was their Opus 510: well over 100 ranks for the newly constructed National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Opus 512 for Newburgh would come a year later.

At Newburgh, an initial acceptance of Skinner’s proposal was interrupted when the members of the church board decided that Skinner’s age (71) might affect completion of the organ. Not willing to be dumped from the running, Skinner secured an extra meeting. Legend has it that this was the moment when he upended his 71-year-old body and walked across the board table—on his hands! There are other versions of the story as well; regardless, one is left with the thought that he must have done something to display his exceptional physical condition. The contract was signed: $17,700 and 34 ranks. Mrs. Harriet Emigh Brown, widow of Judge Charles F. Brown, gifted $20,000 to the church to cover the cost of the organ and the necessary prep work for the chamber.

Calvary’s organ was built at a time when there was often more money available than there was space for the instrument. Like so many other organs, Opus 512 was nearly overflowing its chambers. At the church’s insistence, Skinner laid it out so that no part covered the large gallery window; however, meeting this agreement necessitated placing the entire instrument within two narrow and high chambers. To say that chamber space is tight would be an understatement. Many stops are split up on two different levels. The treble pipes of the Swell are so close to the ceiling that tuning access is compromised. There’s simply too much organ within the two cases, but the church is a large, high-ceilinged room seating over 800, and it needed an instrument of this size. Despite the layout, the organ is well placed in the rear gallery, and it fills the building nicely. Mechanically, it’s another Skinner success story; tonally, it’s a bit tame. From a service-access standpoint, the most important tool of future technicians may be patience.

Fast-forward to 2020. In the early hours of March 5, the church’s attached fellowship building burned nearly to the ground. The billowing smoke from the fire easily found its way into the church proper. Everything was covered with soot—including the Skinner. The insurance company hired a consultant, and it was decided that the instrument would be completely removed, cleaned, and releathered. We had cared for the organ for five years, and ours was the firm selected to complete the work.

The project saw the entire instrument removed from the building. Every part was cleaned and totally reconditioned. We were somewhat surprised at how closely the workmanship reflected that of the original Boston Skinner firm. It made us ponder who and how many joined E.M. at his new venture in Methuen. The only places of compromise we found were that, overall, pipes were built of thinner-than-average metal. Foreign opus numbers on some pipes indicate that they were leftovers from other projects (not entirely uncommon). The Great Diapason is made up of pipes from two other organs; it sounds fine. Skinner’s first years in Boston were plagued by his propensity for tossing in a 32′ stop to help clinch a deal. Arthur Hudson Marks put an end to that; however, now at Methuen, Ernest was again in charge of everything, including finances. Might the twelve 32′ Fagotto pipes here reflect another deal-clincher? Indeed, their sound is excellent; however, their size didn’t help in the lack-of-space issue.

At our shops, the thinness of the pipe metal slowed all work involving it. Not surprisingly, the pipes needed much metal repair and of course had to be handled very carefully to ensure that they’d still be dent-free when they were reinstalled. The French Horn and its chest were missing, and the Vox Humana had disappeared years earlier. There was also a mild change in the chest pitmans: depth of motion was achieved with thick paper gaskets rather than actual borings of the pitman wells.

Besides much pipe repair and a total reconditioning (including every gasket and valve in the organ), our improvements were essentially to shift equipment where possible to create space for better service access, especially in the Swell. Needless to say, the chambers are well lit, with new LED fluorescents mounted above and below the chests. The typically beautiful Skinner console was completely reconditioned and retrofitted with state-of-the-art equipment and organ relay. The Spencer blower’s motor and impellers were removed and inspected. The motor’s bearings were replaced.

There were other E.M. Skinner & Son organs built at Methuen; however, most of the work and opus numbers reflected reconditioning of and modifications to existing pipe organs, not new instruments. One can only hope that there are other original examples still in use. Our undertaking, made more difficult by the organ’s very compact layout, was a big one both for us and the church. We offer special thanks to all at Calvary who cooperated so well with our crews to bring the project to fruition.

Mike Foley is president of Foley-Baker Inc.