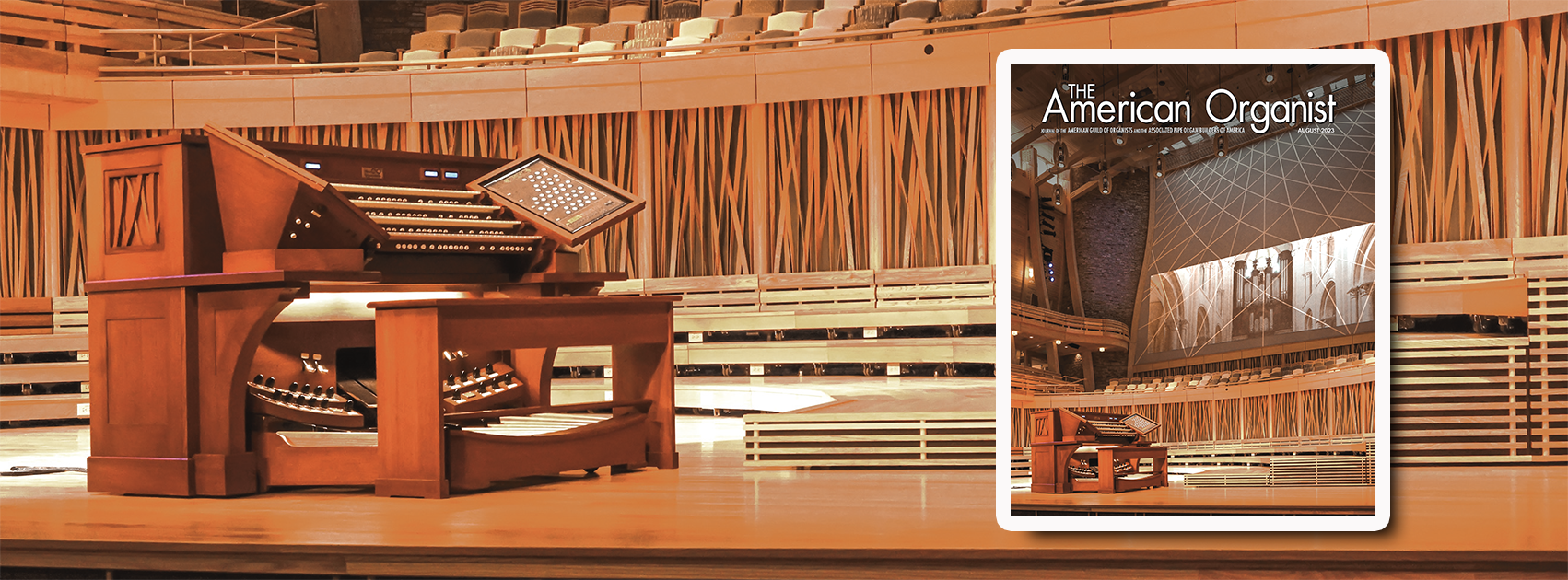

Groton Hill Music Center

Groton, Massachusetts

Meta Organworks

Argyle, New York

Sample Set Collection

By Daniel Lemieux

The story of the Groton Hill Music Center’s concert hall organ begins with Richard Hedgebeth. I think Richard and I saw ourselves in each other: two old-school, innovation-driven pipe organ builders. While old-school and innovation-driven may seem mutually exclusive, the reality of the organ is that it thrives on invention—think Barker levers, electric blowers, and combination actions, or even conceptual innovations like the Baroque revival. In contrast to most other traditional musical instruments, the notion of radical, perpetual evolution is embedded in the organ’s DNA.

Sometime in the early 2010s, independently of each other, Richard and I started exploring the most controversial organ innovation of our time: virtual pipe organ (VPO) technology—even though we had spent our respective careers dismissing speaker-based organbuilding. Richard had settled into a city in which I had some work—Binghamton, New York—and during my tuning season visits, we’d go out to dinner and talk organ. Richard was the only other organbuilder I knew who openly embraced VPO technology.

After the fourth version of Hauptwerk software was released (it’s now up to version 7), I began to realize that VPO technology was a revolutionary development. Many organists were engaging with the software by converting older digital organs, using slave synths, or buying hardware from Classic MIDIWorks in Canada. Some were even posting great-sounding recordings on YouTube or ContreBombarde.com, made with the software’s excellent onboard recording capabilities. It was a grassroots groundswell of users all around the world. When something viral is happening, something important is happening.

After 20 years of full-time traditional organbuilding, I had developed an artistic itch for innovation and growth that desperately needed scratching. So I began to use profits from my traditional organ business, Lemieux & Associates Pipe Organ Company, to absorb the research and development needed to elevate Hauptwerk’s VPO sound engine. My goal was to use a refined hardware set and an ergonomic user interface (i.e., console), as well as high-level programming and voicing protocols, to create a rock-solid, truly musical performance instrument—think Silicon Valley meets traditional artisan organbuilder.

By May 2015, after returning from a monthlong sabbatical in Japan, I was champing at the bit to build a professional-quality virtual pipe organ. I planned to do that by taking high-definition pipe samples very seriously. Richard and I were from different generations, but we found ourselves on the same path. And while neither of us had brought a big-budget virtual pipe organ into the real world, the opportunity was right around the corner.

In 2018, Richard landed the most significant commission of his career: Groton Hill Music Center, a brand-new, state-of-the-art, 1,000-seat concert hall and educational music facility outside of Boston that was in the early stages of construction. Since the building itself was so ambitious and costly, it had been decided early on that it would not be home to a real pipe organ. However, those in charge of planning were amenable to a virtual solution—one that would complement this innovative performance and education space. Richard was a man with a plan, and it was a pretty good one.

Tragically, in 2019, my friend and mentor, then in his early 70s, received a terminal diagnosis of stage-four cancer. Richard contacted me shortly after receiving the news and started the process of bringing me into this job. Sadly, he died within four months. In this period of time, we had some extremely meaningful conversations. I’ll never forget the generosity and bravery he showed in blazing a new path forward for the virtual pipe organ in the last decade of his life.

I was already four years into building Meta Organworks when I took over the Groton Hill VPO commission. Six years and one pandemic later, in early 2023, the building and organ were finished.

I came up with our business name, Meta Organworks, two years before Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook rebrand, so I’m sticking with it. It perfectly expresses what we’re doing on several levels: A Meta organ is an organ of organs (like metadata is data about other data). But more importantly, it expresses a metamorphosis for the pipe organ in our age of virtual reality. And on a personal level, it represents a metanoia: a complete change of heart in the spiritual sense. I am an organbuilder who went from being totally disinterested in speaker-based instruments to dedicating the rest of my career to them—a builder striving to be the “Johnny Organ Seed” of live-performance virtual pipe organs for church, concert, home, and broadcast. One day, I even hope to build traveling “village green” VPOs, to flood the downtowns of this world with organ music.

Serendipitously, Richard and I shared a mentor in the New England Conservatory professor Donald Willing. Richard was a student of his, but Willing had long passed before I came to the organ in the early 1990s at age 13. However, I had a teacher in high school who studied with him and built a magical mythology around his beloved mentor. To this day, Donald Willing is my organ guru.

Willing wrote and self-published a little book: Organ Playing and Design: A Plea for Exuberance. He knew that playing and building organs were two sides of the same coin, and that to keep our art form relevant and vital we needed to embed it with the vitality of the living and the essence of now. He was among the first to wholeheartedly embrace the Baroque revival, and then, right in the middle of the movement’s meteoric 40-year rise, he warned that antiquarian performance practice was a slippery slope—something fast becoming a pedantic, elitist drag on true, relevant, vibrant artistry. He was definitely a “stir the pot” type of guy.

A few years back, we republished Willing’s book (available as a PDF here). I wrote a foreword to this forgotten gem that served as a manifesto for what I was embarking on: a complete reinvention of the digital pipe organ for our age of virtual reality. But, regarding the relationship of the organ to its glorious past, I was going to thread that needle: the organ of the future, based on access to many great instruments from around the world and throughout history (including modern, eclectic ones), all from one universal console and audio system.

For me, this meant using real organ-industry console components, as well as audio equipment from high-end industry leaders (speakers and amps have come a long way in the past 20 years). But more importantly, I felt that the organ console needed a redesign that would reflect the VPO movement. The most obvious element of this is the use of touch screens for stopjambs. They are a natural fit for VPOs, because the software sound engine provides access to multiple complete organ sample sets. With each new instrument, the touch screens change to a virtual stopjamb with the original organ’s layout. Most also have a simple jamb that provides a quick and easy single-screen stop-selection layout. The versatility of touch screens is key, and their perceived negatives are just that.

For a professional installation, a traditional organbuilder’s mindset—particularly with regard to voicing and on-site tonal finishing—is imperative for a successful translation from virtual building blocks to the reality of a live instrument in an actual performance space. The goal is to be respectful of the great works of master builders—instruments that have withstood the test of time—making them sound natural and musical in different acoustics. Just like playing the works of great composers, it is an interpretive art.

Behind the front projection screen of the concert hall (designed to be permeable to sound), we installed a state-of-the art audio system designed uncompromisingly around the sonic needs of high-definition pipe samples. We ended up at just under 50,000 watts for a 1,000-seat, five-story room, and we developed a careful 32-channel distribution of frequencies (Hz), so that, rather than stomping on or muddying one another, the pipe samples retain as much clarity and autonomy as possible. Our aim was to get as close to the natural behavior of an acoustic organ installation as possible, but free from the space limitations of real pipes.

I would never argue that a virtual instrument is better than or even equal to a fine acoustic one. A great pipe organ, in a great room and well maintained, is impossible to beat, but if everything is done well with VPO technology, a very musical instrument can emerge.

Perhaps the greatest consolation prize for not having the “real deal” is the availability of a remarkably varied stable of virtual organs (and temperaments, recording abilities, etc.). The whole concept is expansive and egalitarian, and it amplifies the tradition (no pun intended). After all, you need the real instruments to create the recorded samples. The dissemination of these important organs draws international attention to them, and this plays out in the real world through extensive discourse—and even visits to the original instruments by us enthusiasts.

Even after 30 years immersed in organ playing and building, I find it remarkable to hear Cavaillé-Coll and Skinner, Walcker and Willis, all side by side; to play Bach on Schnitger, then on Silbermann, then on wildly different organ styles; to try many temperaments, at the organ’s original pitch and then at 440. This technology fills in the knowledge gaps created by real-world limitations and provides an immensely useful learning tool.

If a traditional organbuilding mindset can be fused with the raw materials of our era, a truly great instrument will emerge. Maybe it’s not real, but it can be every bit as musical and inspiring as a great pipe organ. Just as importantly, it can expand the pipe organ’s influence as an artistic vehicle. Something quite egalitarian indeed—exactly what the organ needs to widen its sphere of influence in our ever-changing world.

Richard: Build in peace, brother. This one’s for you.

Acknowledgements

As everyone knows, organbuilding is a team sport. Richard and I could not have done it without a small army of great people around us. The Meta Organworks staff responsible for bringing the project to life are Melissa Burbank (project manager), Jim Hutchison (technical designer), and Jack Case (audio/acoustic consultant), as well as project consultant Randy Steere. Of course, many others played smaller roles, for which we are very grateful.

We also thank the people of Groton Hill Music Center (Lisa Fiorentino, Matt Malikowski, Jackson Hudgins, Alex Hug, Mark Mercurio, and Mark Michaud), who facilitated this project in so many ways. Groton Hill shares the transformative power of music through both teaching and performing, in ways that are both innovative and egalitarian.

Daniel Lemieux is CEO and artistic director of Meta Organworks.

To hear recordings of the instrument, visit metaorganworks.com/concert-hall.