Glen Foerd

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Kegg Pipe Organ Builders

Hartville, Ohio

Stoplist

When an organbuilder is asked to restore a significant pipe organ to which known changes have been made, the builder has to expect some surprises. The 1904 Haskell organ of the Glen Foerd house in Philadelphia was to reveal quite a surprise when Kegg Pipe Organ Builders removed it for restoration.

Charles S. Haskell founded the Haskell firm of Philadelphia in 1888 after leaving the Roosevelt Organ Company. He was eventually joined in the family business by sons William and Charles E. Haskell. William, the older son, began his own firm in 1901; it was soon absorbed by the Estey Organ Company, where his many pipe and mechanical inventions were used in Estey instruments. His father and brother continued building Haskell organs. Upon his father’s death, the firm passed to Charles E. The company went bankrupt in 1923, and Charles continued in the pipe organ industry until his death in 1946.

In 1895, Robert and Caroline Foerderer purchased the Glengarry house in Philadelphia. They engaged the architect William McAuley to substantially alter and expand the home to their liking, beginning in 1902. As Caroline was an organist, the renovated house was to include a pipe organ. Completed in 1904, this instrument is an early example of a home organ in the United States, but it is not typical of the organs that would follow in other homes of the wealthy. This was an instrument for an organist, and it was patterned after typical church and small concert hall organs of the day. While it does contain a paper roll player, this is a simple device that plays only notes, leaving stop selection and expression to the person in control.

The organ is located in the stair hall, where it speaks unimpeded to all parts of the home. Built with tubular-pneumatic action on slider chests, with a manual compass of 58 notes and a pedal compass of 27 notes, the instrument was rebuilt in the early 1920s to operate on electropneumatic action. During this rebuild, the original chests and double-rise reservoir were retained, and the compass was expanded to 61 notes in the manuals and 30 notes in the pedal. This work is believed to have been done by the Haskell company, and it included substantial rebuilding of the console, with the addition of a combination action.

Tonally, the organ is almost what one might expect. The first surprise is the presence of a 2′ flute on the Swell. This is original, and the stop is reasonably big, fully complementing and completing the 8′ and 4′ ranks. The Swell Diapason is very different from the Great: narrow scale with wide mouths. Its texture leans heavily toward a broad string. Another surprise of the organ is the Great 4′ Gemshorn. The pipes are engraved with the name Gemshorn, but that is where the resemblance ends. The stop is cylindrical and is musically an Octave. Why it was called a Gemshorn, only Mr. Haskell can say. But this stop melds with the 8′ Diapason in a quite satisfying chorus for the space in which it lives. This is the disposition that we found when removing the organ, but the biggest surprise was elsewhere.

When we first toured the organ and grounds, we were given a tour of the carriage house. This structure was built for actual horse-drawn carriages and is quite large, complete with a counterbalanced manual elevator platform large enough to lift entire carriages to the second floor. In the second story of the carriage house, we were shown a pile of wooden pipes of unknown origin. These Melodia pipes were innocent and ordinary in appearance, and I gave them little further thought. Barns and carriage houses tend to sprout organ pipes for some reason, and this dirty pile seemed unimpressive. When we were removing pipes from the organ as we began its dismantling, however, I noticed that there were places for some large wooden offset pipes in corners of the Swell division. These note positions had no air supply and were clearly for wooden pipes. When vacuuming decades of dirt off the toe boards, it became clear that the Vox Humana, while a typical and expected stop in an organ of this era, was not original. In a single place, we found the word Saxophone written for the offset pipes. The light was dawning. I went to examine the “ordinary” pipework back in the carriage house. Were these not Melodia pipes?

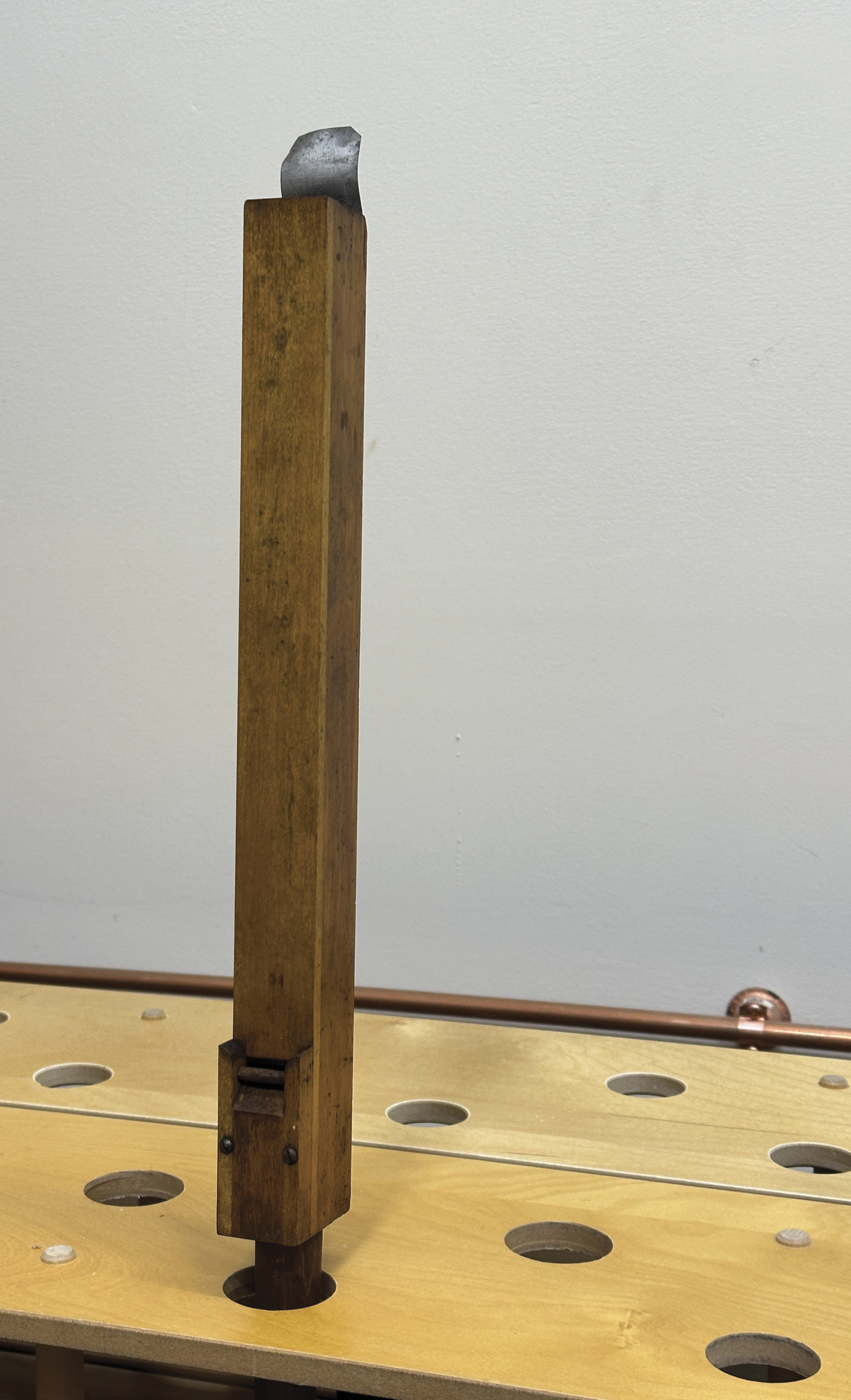

Upon close inspection, it became clear that these dirty pipes, which had haunted the carriage house for nearly 100 years, were an early example of a Haskell labial Saxophone, original to the organ and replaced during the 1920s rebuild by a Vox Humana. While the rank appeared to be an ordinary Melodia, one blow by mouth immediately made the difference known. This was a strong stop of a character quite different from a Melodia—full, edgy, and beautifully textured. After consultation with donor Fred Haas and the Wyncote Foundation, we made arrangements to return the Saxophone to its original position and function. New pipes were made to replace missing ones, and this most interesting example of a Haskell Saxophone will soon play again.

We removed the organ in late 2022, and it will be completed and reinstalled in late 2023. I would like to thank Ross Mitchell, director; Trent Rhodes, assistant director; and Amos Amira, facilities manager, for their eager and unending support. We especially thank Fred Haas and Kristin Ross of the Wyncote Foundation for the underwriting of this fun, important, and exciting project.

Charles Kegg is president of Kegg Pipe Organ Builders.

Photos by Julia Staples (except where noted)

Kegg Pipe Organ Builders

Erika Barnes

Philip Brown

Mike Carden

Joyce Harper

Philip Laakso

Brian Mattias

Nick Myers

Bruce Schutrum

Paul Watkins