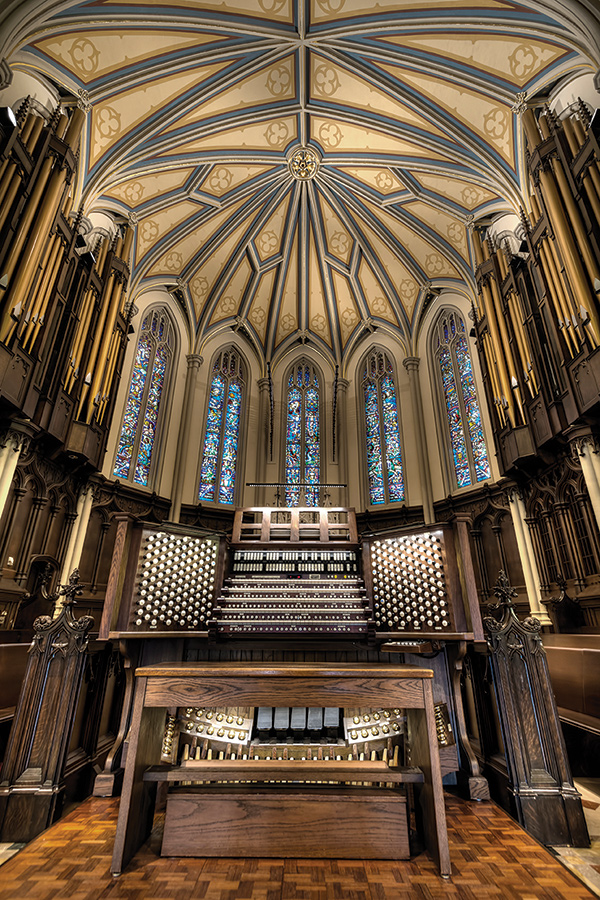

Holy Trinity Lutheran Church

Buffalo, New York

Parsons Pipe Organ Builders • Integrated Organ Technologies Inc.

New organ projects have the luxury of starting from scratch. After evaluating the acoustics, placement, and people, the builder can create a design that (hopefully) suits everyone, perhaps even himself. In the best situations, the builder is given carte blanche, much like a novelist with a blank page. It is often under such circumstances that masterpieces result.

By contrast, rebuilds are another breed altogether. They enjoy neither the luxury of restoration (with its discipline of no change) nor that blank page of new-organ creativity. In place of the novelist starting from scratch, the rebuilder is akin to the writer adapting a novel for the screen, with the characters and plots all largely in place. Still, the rebuilder hopes to find room for creativity, improvement, and transformation. After all, some of the world’s greatest organs are rebuilds; consider Saint-Sulpice in Paris or Woolsey Hall at Yale University. But in these instances, a sufficient infusion of new material allowed Cavaillé-Coll and Skinner to fashion a result fully recognizable as their own work. Our project at Holy Trinity, Buffalo hardly began so loftily.

The Buffalo organ’s many-chaptered history began as a 1949 three-manual M.P. Möller. In terms of construction and voicing, the best surviving pipes came from these original 43 ranks, itself a quaint number considering the subsequent enlargements that raised the tally to 151 ranks and eleven divisions. Much of this expansion came from Möller, who embellished the chancel sections, added a new Positiv, Grand Choir, and Solo, and eventually installed a two-manual gallery organ. Later in the 1980s, Allan Van Zoeren revoiced much of the chancel fluework, adding other voices and supervising colleagues in console revisions. While the organ unquestionably grew in color and scope, inside it was an ever-increasing web of chests, pipes, and challenging access.

In 1994, Charles Kegg took the organ in a new tonal direction. He revoiced certain stops for greater breadth and warmth, installed new chorus reeds in the Swell and Grand Choir and new upperwork in the Great and Swell, and enlarged the gallery Swell and Positiv. Much of this effort took the organ closer to its 1949 late-romantic roots, only now within the context of a vastly larger size. But even this project was insufficient to overcome the organ’s ungovernable mechanical nature, mostly due to accessibility.

We entered the picture in 2012 as the organ’s caretakers. With drafty chambers and pipes on numerous levels, this work was rarely satisfying. In time, certain failing aspects could no longer be ignored. Möller pipes in the facade and Grand Choir were collapsing, and certain chests needed releathering. But thanks to the gentle persistence (spearheaded largely by Dave McCleary and Matt Parsons) and the foresight of Intentional Interim Pastor Rev. Neil Kattermann to intervene on behalf of the congregation and organ, initial requests for repairs were eventually parlayed into a phased plan. First, the main organ (Great, Swell, Choir, Positiv, and Pedal) would be remanufactured: new windchests, winding, and swell boxes; the entire organ rewired with a new control system and five new manuals in the main console; collapsing pipes replaced; and modest refinements made in Grand Choir and Solo. Future phases include chassis replacement in the Grand Choir and Solo, and a complete overhaul of the gallery. As it has from the start, the Margaret L. Wendt Foundation generously funded this latest campaign, always convinced that Holy Trinity’s musical mission was of material benefit to the city of Buffalo.

In remanufacturing the main organ, we were given—at least mechanically—that all-important blank page. First, the church agreed to strengthen the chamber walls, to project tone and limit outside climate interference. At the same time, they agreed to increase the nave-facing opening, to aid in clarity and effectiveness of projection, thus making the chancel organ less dependent on augmentation from the gallery for normal Sunday use. An internal air circulation system (which we have done elsewhere with great success) combats stratification and helps keep the tuning stable. Finally, and critically, we could redesign the entire chamber.

Our engineer Peter Geise (an Eastman-trained organist who studied further at GOArt in Sweden) and our tonal director Duane Prill (also Eastman-trained, and Marian Craighead’s successor as organist at Asbury Methodist in Rochester) collaborated on the new layout. They strove for an arrangement that would make not only good musical and mechanical sense, but be as inviting to the tuner as the old layout had been daunting. In the old setup, the Great and Positiv spoke into the chancel; the Swell and Choir were against the right wall, with the Swell above. That division spoke mostly out of the chancel facade, while the Choir, down low, had an odd tonal access to the congregation through the former squat nave opening. Climbing through the organ was not for the faint of heart. Certain pipes could not be reached by any means (including portions of the Positiv 8′ Principal); indeed, the average child’s jungle gym was easier to navigate.

In our new layout, the Great is behind the nave opening, from which it speaks directly to the congregation. The Positiv is essentially where it was, speaking into the chancel as a mini-Great. The Swell and Choir are placed against the chamber’s rear wall, with shutters facing both chancel and nave. The Pedal is divided between the main Great chest (4′ Spitzflöte, mixtures), and lower level (flutes, principals, reed). Thick maple swell enclosures create a pianissimo new to this instrument; nave-facing shutters can be switched off for accompaniment. All of these improvements combine to give the organ an entirely different impact in the room: warmer, certainly clearer, and in every way more satisfying.

Slider windchests carry most of the material, with unit windchests for extended stops and chorus reeds. Among some electric-action devotees, slider windchests have an uneven reputation, particularly concerning poor repetition, unwelcome drawing between stops, and ugly releases from small pipes. In the windchest design, great care was taken to address each of these issues. To ensure responsiveness, each traditional pallet has an accompanying all-electric valve, breaking pluck and speeding response (an idea hardly new to us, merely carried out methodically here). Note order was planned such that no one group of notes would have an advantage in egress over any other (lessons learned from some of our other jobs using tierce-layout chests in chambers). Similar forethought was extended to the order of stops on each chest, to negate interference and drawing, and promote secure tuning and speech. Dividers inside the note channels isolate various stops from unwanted entanglements; careful adjustment of pallet springs (both main and tail) eliminates any unappetizing “weeping off” of trebles. The result has all the advantages of slider chests—tight tuning and uniform attack for chorus work—without undesirable side effects. Finally, given the space-efficiency of slider chests, and the fact that almost any winding system would be simpler than Möller’s, the former constricted feeling has given way to one of spaciousness and order. A generous stair-ladder connects the two levels, no walkboard is narrower than 18″, and every surface is bathed in LED lighting.

At first, this project involved no tonal changes. But once Duane Prill had reviewed all stops with musician James Bigham, together they agreed that certain minor aspects could be improved. A round robin of flute exchanges between Great and Choir, together with a vintage Concert Flute, has improved that complement of voices. The formerly mute nave facade has become a new Great 16’´ Principal, while a new 16’´ Violone replaces the old 16’´ Principal in the chancel facades. As stops were auditioned in the workshop, it became clear that Parsons had an opportunity afforded no prior rebuilder: to review all the pipes at the same time by one tonal team. Thus, Duane Prill seized the moment, revoicing the Great, Swell, and Positiv choruses, taming the Grand Choir upperwork somewhat, and making useful adjustments to solo voices such as the Flauto Mirabilis and Viole Celeste II. Extending over a six-month period, the tonal finishing put the organ within Parsons’s house practice, promoting a balance of warmth and clarity, accompaniment and repertoire, together with a natural but not antagonistic treble ascendancy.

Eight reeds were sent to Broome & Co. LLC for reconditioning, including chorus stops from the Great, Swell, and Pedal, and the Choir Trompette and Cor Anglais. Most are as before, but better (more uniform in timbre and secure in tuning). An exception is the Pedal reed, now speaking on nine-inch wind pressure and revoiced as a commanding melody voice. The remaining reeds were cleaned at Parsons, and altogether this array features outstanding examples of both neoclassical and orchestral colors. Apart from simple cleaning, the Grand Choir and Solo reeds await renovation in a later phase. However, the collapsing Grand Choir 32’´-16’´ reed was replaced by a new set from A.R. Schopp’s Sons, scaled and voiced by Broome along Skinner Waldhorn lines. Finally, the old “Tuba” (a strident voice made out of an old Cornopean, with little actual tuba quality) was replaced with the new Bigham Tuba, given in honor of Mr. Bigham’s 40 years’ service to this church. Also voiced by Broome, this superb stop equals any Willis or Skinner set, fully justifying our pleasure in working with this talented artist.

Control systems for a two-organ, two-console instrument, particularly when the consoles are not identical, are the most challenging and time-consuming to design and execute. With 11 divisions, 283 stop and coupler controls, and 189 pistons on the chancel console alone, some idea of the complexity comes into focus. In addition, Mr. Bigham was eager to preserve a number of nonstandard controls, making this one of the most complex systems ever. The challenge was ably met by the Virtuoso Control System from Integrated Organ Technologies Inc. In the past, activity at one console can affect the other adversely. IOTI’s innovative multiplexer reduces this complexity by enabling each console to control the entire instrument independently, one unaware of what is happening at the other. Dwight Jones, IOTI’s president, was on site on numerous occasions and patiently accommodated every request—a true colleague. In that same way, we have felt uncommonly welcomed by the Holy Trinity staff. Pastor Lee Miller treated us with unfailing cordiality through additional requests, changes, and obstacles. Anytime we needed something, buildings and grounds director John Busch was there; Linda Lipczynski is that smiling, helpful presence you wish ran every church office.

Finally, we give thanks to James Bigham, who knew the organ had its troubles but was initially averse to any change. Change it did, perhaps not in that far-reaching Saint-Sulpice or Woolsey Hall manner, but transformationally nonetheless. Mr. Bigham walked that road with us, tentatively at first, but with ever-increasing confidence as the results justified our efforts. In turn, his encouragement allowed us to do more than we had thought we could. That process has created, in our view, the best version of this organ yet.

For the stoplist, technical details, and photos: Parsons Organs and Facebook

Parsons Pipe Organ Builders

Richard B. Parsons, president

Calvin G. Parsons, vice president

Duane A. Prill, tonal director

Joseph Borrelli

Autumn Coe

Aaron Feidner

Dan Gagne

Peter Geise

Aaron Grabowski

Tina Macaluso

Tony Martino

David McCleary

Ellen Parsons

Matthew Parsons

Timothy Parsons

Brenda Rizzo

Dick Schaefer

Jay Slover

Dale Smith

Chad Snyder

Bernard Talty II

Integrated Organ Technologies, Inc.,

Dwight Jones

Maynard Fitch

Steve Mobley

On this project, Jonathan Ambrosino of Boston acted as in-house adviser to Parsons (client relations, chamber and windchest design), assisted Mr. Prill with all on-site tonal finishing, and wrote this article.