St. John’s Seminary, Brighton, MA

Andover Organ Company, Lawrence, MA

By Matthew M. Bellocchio

When renovating a historic building, it is often necessary to strike a balance between preserving the original fabric and updating it to suit modern needs. When renovating century-old American organs, similar choices must often be made. A conservative restoration is the logical decision for an exemplary work by an important builder or a small organ in a rural church with modest musical requirements. But an aging instrument with unreliable mechanisms and limited tonal resources, in an active church or institution with a professional music program, requires a careful assessment of each of its existing components. This was the case with the 1902 Hook & Hastings organ, Opus 1833, in the St. John’s Seminary chapel.

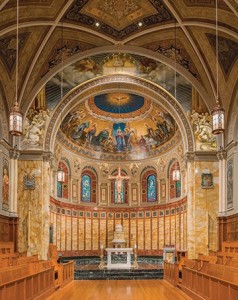

The seminary, founded in 1884 by Archbishop John Williams, is situated in a parklike setting in northwest Boston. The 1899 Romanesque Revival chapel, designed by Boston architects Maginnis, Walsh and Sullivan, was first used for services in 1901. Gonippo Raggi (1875-1959), an Italian artist who decorated many important Catholic churches and institutions in the United States, painted its elaborate murals. The vaulted ceiling, and the marble and oak wall paneling, create a reverberation time of four seconds when the 300-seat chapel is empty. Although the chapel is visually and acoustically magnificent, its organ was less so. On the cusp of the 20th century, Hook & Hastings was in transition. Its golden period was well behind it; the Hook brothers, Elias and George Greenleaf, were dead, and their chosen successor, Francis Hastings, was in his 60s. Wanting to preserve its good reputation, yet keep up with changes in organ technology, the company had one foot in each century. While its smaller organs still used mechanical action, larger instruments had traditional slider-pallet windchests fitted with experimental pneumatic actions.

After nearly a century of use and constant winter heating, the chapel organ’s windchests and actions developed serious problems, including numerous ciphers and dead notes. The Hook & Hastings console was replaced in 1946. When the replacement console failed in 2004, a one-manual 1850s Simmons tracker was put in its place to serve as a temporary instrument until the chapel organ could be rebuilt.

Our lengthy experience with Hook & Hastings organs has taught us that their early electro-pneumatic actions are cumbersome, slow, and difficult to repair. Therefore, we reused the pipes, windchests, and most of the original parts of Opus 1833 as the basis of an expanded instrument with a new electric action.

The organ’s cantilevered case originally had a simple facade of three tall fields of pipes among four Ionic columns. During extensive chapel renovations in 1946, Maginnis & Walsh added a large new top section, with three Romanesque arches, to transform the case to resemble an Italian Renaissance organ. But the pipes, with Victorian-style bandings and colors, were not repainted. The result was a Victorian-Italianate conglomeration.

To rectify this visual hodgepodge, we turned to our colleague Marylou Davis of Woodstock, Connecticut—an expert in the conservation and recreation of historic decorative finishes. We have collaborated with her on several organ facades, most notably our Opus 114 in Christ Lutheran Church, Baltimore (featured in January 2013 TAO). Don Olson, Andover’s retired president and visual designer, worked with her to design a new decorative treatment for the seminary’s facade pipes that would harmonize with the Italian-Renaissance-style case and chapel.

Marylou chose a palette of gray and neutral tones for the facade pipes to complement, rather than compete with, Gonippo Raggi’s murals. Spiraling acanthus leaves and optical tetrahedron patterns, which suggest embossed pipes, evoke a Renaissance style of ornament. The center pipes are highlighted in red ochre, with overlaid geometric forms that imitate the inlaid marble panels of the apse. The pipe mouths are gilded in rose-colored 23-karat gold leaf and glazed for a soft, aged appearance. As a crowning flourish, the cross surmounting the case is painted in faux lapis lazuli.

We built a new, solid-white-oak console in the style of the Hook & Hastings original. Its design, with a lyre music rack and elliptically curved stop terraces, is based on the console of Hook & Hastings’s Opus 2326, built in 1913 for the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola in New York City. In the 1950s, the St. Ignatius organ was moved to a Catholic church in Lawrence, Massachusetts, just two miles from our shop, where it still survives. To meet the demands of a 21st-century music program, this reproduction console has state-of-the-art components, including a Solid State Organ Systems recording module and Organist Palette, which permits organists to program the piston combinations and sequences remotely, with an iPad.

Most of the 1902 Hook & Hastings organ was located within the case, with Swell above Great and the wooden Pedal 16′ Open Diapason pipes at each side. At the upper level—behind the Swell, in a 15-foot-deep unfinished gallery—were the organ’s large reservoir and Pedal 16′ Bourdon. We moved the Pedal Open Diapason pipes from inside the case to the rear gallery, which now accommodates all the Pedal stops and reservoirs, as well as the new blower. There was sufficient space inside the case behind the Great chest to add a small unenclosed Choir division.

We completely rebuilt the Great and Swell slider chests and constructed a new one for the added Choir division. All three chests have marine-grade plywood cables and pallet boards, which will not shrink or crack from constant heating, and new electric pull-down magnets and slider motors. The 1902 Hook & Hastings organ was winded from a single, weighted 6′ x 9′ double-rise reservoir in the gallery behind the organ. Large wooden windtrunks at both sides conveyed ample wind to the chests. This traditional American style of wind system provides a solid, yet somewhat responsive, wind supply typical of earlier Hook organs. We retained this winding for the manual chests and added a separate reservoir for the enlarged Pedal division.

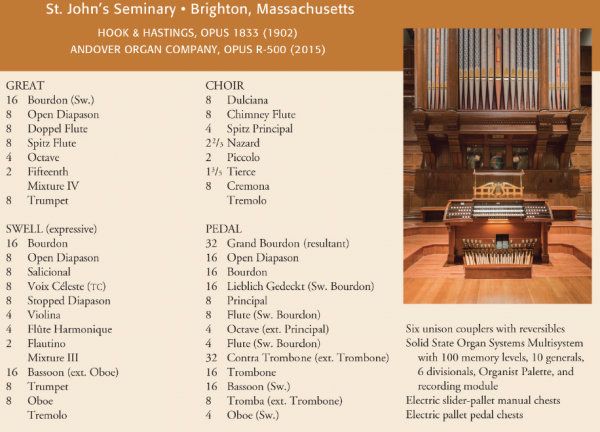

Hook & Hastings Opus 1833 was a modest two-manual, 18-rank instrument with a standard stoplist for the period. The Great had principals at 8′, 4′, 2′, plus 8′ Doppel Flute, Dulciana, and Trumpet. The Swell had flutes at 16′, 8′, 4 ‘, an 8′ Diapason and Salicional, a 4′ Violina, a three-rank Dolce Cornet and an 8′ Oboe. The Pedal had just a 16′ Open Diapason and 16’ Bourdon. While this specification worked for accompanying chants and hymns, it lacked the choruses and colors needed for organ literature.

There were also some pipe scaling issues. The Great 4′ and 2′ principals were both six scales smaller than the very large scaled 8′ Open Diapason, resulting in a preponderance of 8′ tone in the chorus. We rescaled the Great 8′ Open Diapason and the 4′ Octave to make a more gradual transition in power between the 8′, 4′, and 2′. We crowned the chorus with a new Mixture and replaced the 8′ Dulciana with an 8′ Spitz Flute to provide a more useful accompanimental stop in this division.

The Swell division had good bones but needed fleshing out. Since the Dolce Cornet’s pipes were missing, we replaced it with a new Mixture to cap the chorus. We added a bright 8′ Trumpet for a chorus reed and extended the 8′ Oboe to provide the richness of a 16′ Bassoon. We also added a 19th-century-style 2′ Flautino, useful with either flutes or principals, and a Voix céleste to complement the Salicional.

The new Choir division provides some softer accompaniment and color stops, as well as a Cornet decomposé. The 8′ Dulciana, moved from the Great, provides a quiet string tone. The 8′ Cremona, a narrow scaled clarinet reminiscent of early Hook examples, is useful for both chorus and solos.

To the Pedal 16′ Open Diapason and Bourdon we added a metal 8′-4′ Principal and a Trombone that plays at 32′, 16′, 8′. The Swell 16′ Bourdon and 16′ Bassoon were also borrowed down to provide softer Pedal voices. The end result of these tonal changes and additions is an instrument of 40 stops, 34 ranks, and 1,994 pipes that is more versatile and appropriate for its expanded role. It still sounds very much like a Hook & Hastings organ, but one from an earlier and better period of the firm’s output.

Andover Organ Company has worked on numerous Hook & Hastings instruments—including the monumental 101-rank 1875 masterpiece, Opus 801, at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston, and the famous 1876 “Centennial Exposition” organ, Opus 828, now in St. Joseph Cathedral in Buffalo, New York. We feel honored to have been selected to rebuild St. John’s Seminary’s 1902 Hook & Hastings instrument that, coincidentally, is the 500th organ our company has rebuilt or restored. We are grateful to Msgr. James Moroney, rector; Janet Hunt, music director; and the rest of the seminary staff and volunteers for their support and assistance throughout this project.

Andover is blessed to have a team of 19 dedicated people, who collectively possess more than 400 years of organbuilding experience. Benjamin Mague, Andover’s president, was the project team leader, and Michael Eaton was the design engineer. Others who worked on Opus R-500 were Ryan Bartosiewicz, Matthew Bellocchio, Milo Brandt, Anne Dore, Donald Glover, Andrew Hagberg, Albert Hosman, Lisa Lucius, Tony Miscio, Fay Morlock, John Morlock, Donald Olson, Jon Ross, Craig Seaman, Cody West, and David Zarges.

* * *

Andover Opus R-500 will be premiered in a “Choir and Organ Commemoration of the Faithful Departed” on November 1, 2015, at 3:00 P.M. Special guests David Woodcock, conductor, and Jan Coxwell, soprano, will join organist Janet Hunt and a festival choir in a concert including works by Howells, Brahms, Dvofdk, and Durufli in honor of All Souls Month.

Matthew M. Bellocchio is a project manager and designer at Andover Organ, which he joined in 2003. A fellow of the American Institute of Organbuilders, he has chaired the AIO Education Committee and served twice on its board of directors, most recently as AIO president.

The Organ in St. John’s Seminary Life

When I began working for St. John’s Seminary in 2005, discussions about the nonfunctioning Hook & Hastings organ had been ongoing for several years. Multiple options had been explored without reaching a definite decision, and funds for a large-scale project were not available. The seminary purchased an 1850s Simmons chamber organ to serve as a temporary instrument. Although it was a lovely instrument, it was not loud enough to accompany the increasing number of seminarians admitted with each passing year. Additionally, its modest size substantially limited the organist’s repertoire.

As the seminary flourished and the number of seminarians increased, we reviewed the organ options, involving national expert Barbara Owen in the discussion. We agreed that, in order to suit the current needs of the Seminary, as well as honor the historic significance of the Hook & Hastings organ, we should renovate the instrument by preserving what was already there and adding to it, so the seminary community could hear and appreciate the enormous wealth of sacred organ music. We chose Andover Organ Company to do this work because of its knowledge and extensive experience in renovating and restoring Hook & Hastings instruments.

What do we hope the renovated instrument will do for us? St. John’s celebrates three daily services with music. Cantors lead the community singing in daily services, and the men’s schola sings at Sunday Masses and for special feast days.The expanded instrument will be put to good use in these liturgies by accompanying singing, and playing suitable voluntaries and improvisations. Now we will be able to feature more significant organ and choral works on Sundays and feast days.

A concert series of sacred music will be instituted. Plans are being made for public workshops focusing on specific aspects of music and worship.

In short,the organ will better equip us to present a vast amount of music from all eras suitable for Roman Catholic worship and to educate future priests about the value of having and maintaining a pipe organ. I am grateful to Msgr. Moroney and all other members of the St. John’s Seminary community who have supported this project and seen it through to completion.

Janet E. Hunt, FAGO

Music in the Seminary Life

For nearly 800 years the organ has accompanied the human voice in singing the praises of God. According to Pope Benedict XVI, the organ is unique among all liturgical instruments in its capacity to echo and express “all the experiences of human life. The manifold possibilities of the organ in some way remind us of the immensity and the magnificence of God.”

It is hardly a surprise, therefore, that Roman Catholic seminaries are called upon to provide the best of musical training to seminarians, including the finest examples possible of what the liturgical organ can be.

In so many respects, the seminary is an intensive microcosm of the Catholic parish. It provides an example of what parish liturgy can be, demanding an ars celebrandi that promotes full and active participation by all, each fulfilling their own role in the sacred mysteries. Music must be at once easy to accomplish but represent the best textual and musical expression that the Church has to offer. Likewise, the liturgical music of a seminary must reach across cultural genres to embrace the whole rich horizon of good liturgical music.

Many newly ordained priests from our seminary will someday be faced with the question of what to do about a poorly maintained instrument, or one in need of replacement—or even a parish with no organ at all. More than anything we can say or do,the mere presence of the best of liturgical organs in our seminary chapel will teach them what they must strive for in such circumstances.

I am deeply grateful to Janet Hunt and the Andover Organ Company, as well as our generous benefactors, for making this fine formational experience possible at St. John’s Seminary.

Msgr. James P. Moroney, Rector