The New Dobson Organ at St. Thomas Church

The New Dobson Organ at St. Thomas Church

In New York City

By John Panning and Jonathan Ambrosino

View the new case

View the 1913 case

View the Stop List

Lovers of church music have long made St. Thomas Church, on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan’s swank Midtown, a place of pilgrimage. Within its landmark Gothic Revival walls, the parish has forged a unique musical perspective, combining a high Anglican choral tradition with organs of French inspiration, a musical practice that strongly informed the tonal design of our recently completed Opus 93. The two basic requirements demanded by this tradition—color and discretion for choral accompaniment, grandeur and panache for solo performance—are found in few historic styles. On the face of it, those goals might even seem contradictory. It is easy to provide a variety of pretty voices on the one hand and blazing full organ on the other—organs with these individual effects are commonplace—but it is quite another to structure everything in between so that the journey from the former to the latter is musically convincing. Exquisite care must be paid to the dynamic and tonal relationship between each voice so that a natural crescendo can be made, and so that balances between each division truly serve the needs of any music at hand.

With very few overtly historical exceptions, our previous work has sought to align points of congruence between differing organ traditions. Our overarching goal is a well-digested and harmonized musical instrument that accommodates the widest possible range of solo and choral literature rather than an assemblage of favorite historical bits. While no organ we have built is more focused upon the support of singing in all its varied forms, the design of Opus 93 did not arise in a vacuum. It mines the same rich ore that inspired our previous instruments for, among others, St. Paul’s Church, Rock Creek Parish in Washington, D.C., St. David’s Episcopal Church in Wayne, Pa., Independent Presbyterian Church in Birmingham, Ala., Merton College Chapel, Oxford, U.K., and the forthcoming instrument for St. James’ Church, King Street, in Sydney, Australia. The instruments created for these places were persuasive to the St. Thomas organ committee, charged to commission an instrument that would support the five centuries of music regularly offered by the parish musicians, a task whose immense breadth would surely bewilder the historic builders who inspire us.

John Scott and members of the committee, assisted by consultant Jonathan Ambrosino, visited not only a number of Dobson organs but also instruments such as the Aeolian-Skinners at Trinity Church in New Haven (Opus 927, 1935) and Church of the Advent in Boston (Opus 940, 1936), which informed fruitful discussions of tonal design. At every point, John Scott’s wide experience and searching mind worked to broaden the organ’s capabilities. The result is an instrument resembling no specific example or style. Instead of literal quotation, the new organ more importantly possesses the confidence and aspiration of the grand instruments created contemporaneously with the beloved repertoire of the Choir of Men and Boys and the solo literature that adorns the parish’s worship services.

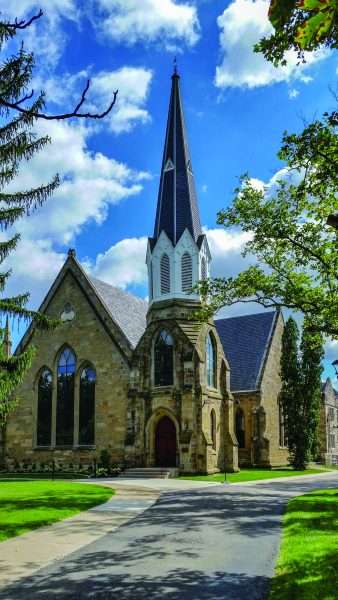

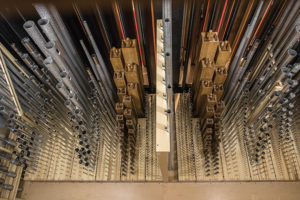

The siting of the new organ was broadly directed by the architectural realities of the 1913 building, the crowning achievement of the partnership of Ralph Adams Cram and Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue. Their plan provided four substantial organ chambers and an elegant organ case, realized, like the rest of the woodwork, by the celebrated Boston firm of Irving & Casson. The case housed the Great division of the original organ, Opus 205 of the Ernest M. Skinner Organ Company, whose Swell was situated behind the case in the northeast chamber (geographic, not liturgical—the church is oriented 180° from tradition). The Choir and Solo shared an enclosure in the southeast chamber, while the Pedal occupied both western chambers. With the almost complete tonal alteration of the organ by Aeolian-Skinner in 1956, the Great moved to an exposed location in front of the northwest chamber, even farther from the nave and with no immediately adjacent reflective surfaces. As from its earlier location in the case, the Great spoke across the choir toward the Chantry Chapel on the south side, where its sound was unusefully scattered, leaving the rear of the nave with paltry support for congregational singing. Aided by acoustical studies, we realized that a Great located on the opposite side of the chancel could take advantage of the reflections offered by the solid north nave wall, which has no lower windows, to direct sound more efficiently to the back. The Great, joined by a Positive below at Chair/Rückpositiv elevation, is now situated in a new organ case opposite Goodhue’s, from which place it speaks with authority to the entire room. The Swell remains in its original place behind the 1913 case; the Choir likewise finds its home in that department’s original location in the southeast chamber behind our new case. We claimed the southwest chamber for a substantial Solo, and retained the northwest chamber for the largest Pedal pipes. The old case has been fitted with new tin facade pipes from the Pedal First Diapason 16′, Octave 8′, and Super Octave 4′, and it houses Pedal upperwork and smaller reeds at a level similar to the Great reeds. The galleries that were formerly the site of thousands of exposed pipes have now been given to the lowest twelve pipes of the Pedal Contrabass 32′; of Haskell construction, they lie horizontally below the railing, out of sight.

Despite centuries of insularity, the English organs that inspired the Victorian and Edwardian composers so beloved by the St. Thomas Choir could be surprisingly cosmopolitan. Many had Saxon roots, transmitted to England primarily by Edmund Schulze. That master’s tonal palette and forthright voicing style, representing a connection back to the workshop of Gottfried Silbermann, were adopted with almost religious fervor by certain British builders, most notably T.C. Lewis, whose singular Southwark Cathedral organ of 1897 was a touchstone for John Scott and us as well. The homegrown ingenuity of William Hill, Henry Willis, and Arthur Harrison likewise had vigorous partisans, and Cavaillé-Coll found British admirers who commissioned substantial organs. In turn, this eclectic body of work spread across the English organ landscape informed the instruments designed at Aeolian-Skinner by G. Donald Harrison, who created his own synthesis. The practices of all these builders are reflected to some degree in Opus 93.

The tonal design of organs from the 18th century and earlier can be described as having vertical structures, referring to the stack of pitches typically represented in their specifications, from foundation pitches rising through mixtures. By contrast, later organs, from the Romantic and Symphonic periods, are said to have horizontal structures, where a wide variety of pitches is often subservient to extensive development of tone color, especially at unison pitch. In Opus 93, to address the organ’s obligation to both solo and choral literature of many eras, both vertical and horizontal structures are thoroughly developed.

Like those German and German-inspired organs that so thrilled English ears in the second half of the 19th century, our new instrument has a fundamentally classical structure framed around bold diapason choruses and flutes of varied construction and treatment. Chief among these is naturally the Great, with diapasons ranging from 32′ to Cymbal and flutes from 16′ through the tierce of the Cornet, but each division, apart from the specialized Solo, has such vertical structures of greater or lesser dimension.

Several important horizontal features allow the Miller-Scott Organ to be an elevated vehicle for choral accompaniment. Foundation color at widely differing dynamic levels fills any accompanimental need, offering overlapping layers of registrational possibility. The tonal range of the organ, especially at the unison level, has been broadened beyond that of any of its predecessors; the Solo alone contains a Flauto Mirabilis of large scale and powerful treatment alongside extremely pungent, small-scaled Violes d’Orchestre of the type favored by Arthur Harrison. In this family alone, we see how a horizontal element has additionally been developed vertically, as the unison and its celeste are joined by an octave and a compound stop of the same remarkable color. Similarly, each of the four manuals and the Pedal has a chorus of French reeds, an overt homage to the Arents Organ’s Gallic character, but they are augmented in the Swell and Solo by additional chorus reeds of Anglo-American design.

This provision of multiples—unisons, 4’s, trumpets, reed choruses—is aimed toward careful interlayering of tone among foundations and choruses, a nod to much of G. Donald Harrison’s prewar ideas in the service of offering multiple gradations of accompanimental possibility. For instance, the Choir chorus reeds slot in between the Swell’s Trumpets and Trompettes, much as the Choir’s tapered diapasons live between the Swell 8′ and 4′ strings and diapasons. The Positive and Great have similar inter-relationships, which themselves refer back to those of the Swell and Choir. Far from being redundant, these multiples give departments, and by extension the whole organ, various ways of arriving at climactic effects. Growing out of these subtleties are soaring solo voices, piquant orchestral tones, new variety in the Pedal, a fresh Positive that reaches right to the back pew, and the blazing drama people loved in the previous organ.

Several aspects beyond the specification are crucial to the organ’s success as an accompanimental instrument. Three of the five manual departments are very effectively enclosed, and several stops from these divisions are available in the Pedal, including the full-length 32′ extension of the Swell Double Trumpet. The physical location of each division is important to its effect in the church. Even here we see vertical and horizontal relationships, not just tonally but physically: a vertical axis of Great and Positive, and a horizontal one north to south through Swell, Positive, and Choir. The veiled character that proper chambers can provide is important to effective swell enclosures; by contrast, the siting of the Positive gives it an immediacy essential for classical repertoire. Finally, more important than the mere presence of “correct” stops or “proper” placement is a voicing treatment that emphasizes clarity and blend, in which pipes speak naturally and articulation is deployed as a marker of promptness, not an effect in itself.

Surrounded by such surpassing decorative beauty, the design of our new organ case logically takes its cue from Goodhue’s, surely one of the best and most well-proportioned examples from his generation. However, we believed the new case should not succumb to a desire for a gratuitous symmetry, nor should it be reduced in size in an attempt to minimize its presence in the choir. While ours has massing similar to the 1913 case and is treated just as sumptuously, it interprets Gothic principles more strictly—the 1913 case, when examined, reveals not so much a Gothic design as a Baroque one with Gothic decorative details. Lynn Dobson made a number of design studies, for which the high altar and especially the Chantry Chapel altar provided crucial inspiration. As seen from the side aisles of the nave, the resulting new case intrudes upon the reredos less than Goodhue’s. Made of quartersawn oak like the surrounding woodwork, our new case displays pipes of the Great Diapason 32′ (32′ A being the largest pipe in the center tower) and First Diapason 8′.

While the original case’s carved musicians and instruments are a visual representation of Psalm 150, the new case honors the four Evangelists and persons of the recent past important to the parish’s music. Bas-relief portraits of Gerre Hancock, Rector XII Fr. Andrew Mead, and John Scott adorn the Positive’s center facade, flanked by portraits of organ committee co-chairs Kenneth Koen and Karl Saunders, Warden William H.A. Wright II, principal donors William and Irene Miller, Rector XIII Fr. Carl Turner, and musicians Daniel Hyde and Benjamin Sheen.

A project this enormous is beyond the sole resources of even the largest organ company, and we are fortunate to have had the assistance of a number of valued collaborators. First of all, the organ committee and its co-chairs, Kenneth Koen and Karl Saunders, the vestry, especially William H.A. Wright II and Kenneth Koen, and the rectors of St. Thomas Church, first Fr. Mead, then Fr. Turner, have provided truly invaluable support and encouragement. Daniel Hyde and Benjamin Sheen were especially encouraging during the tonal finishing of the organ, when we felt most keenly John Scott’s absence. The church’s staff, especially Barbara Pettus and Angel Estrada, bore with us from day to day and provided unflaggingly cheerful assistance in matters too numerous to count. Robert Silman Associates undertook the structural engineering for the support of the new organ case, and Dawn Schuette of Threshold Acoustics provided valued expertise for the acoustical improvement of the organ chambers. Daniel Wrzesinski of Westerman Construction, the parish’s project management firm, coordinated the work of our firm and the various contractors. Dennis and Denny Collier of Bangor, Pennsylvania, and their band of brilliant artists spent four years creating the carving that enriches our new organ case. Foley-Baker Inc. restored the original Spencer organ blower, now entering its 106th year of service, and removed the Arents Organ in the summer of 2016. Lawrence Trupiano, organ curator, assisted with the removal of the Arents Organ and has supported us and the project in countless other ways. The experienced men of Sapsis Rigging worked alongside us for months to install with care and creativity the many large parts found in a pipe organ of this magnitude. Our installation crew was enlarged by colleagues Richard Frary, Andrew McKeon, Sean O’Donnell, and Jonathan Ortloff, who found time in their busy professional schedules to offer us many weeks of assistance. Christopher Broome skillfully voiced several Solo reed voices. Through it all, indeed as one constant in a decade-long project, consultant Jonathan Ambrosino has been the essential link between us and these good people, serving unstintingly as counselor, facilitator, and technical resource.

And with equal measures of sadness and gratitude we remember our friend John Scott, whose quiet wisdom shaped this project from the beginning. Our world is a better place because of John’s gentle humanity and towering musicianship, and it is tremendously appropriate that Opus 93 is named in his memory. Much as we might wish John back to assume his place at the center of St. Thomas’ musical life, he knew better than many that pipe organs are not built for individuals and their whims, but for a life of service to their parishes. We commend this instrument, created through the efforts of so many hands, to the people of St. Thomas Church. May it long serve to glorify God, refresh His people, and be a witness of His gifts to the people of New York City and beyond.

John A. Panning, Vice President and Tonal Director

Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

Lake City, Iowa

Dobson Pipe Organ Builders

William Ayers

Abraham Batten

Kent Brown

Lynn A. Dobson

Randy Hausman

Dean Heim

Donny Hobbs

Ben Hoskins

Bryan Jimmerson

Arthur Middleton

Ryan Mueller

Jan Ourensma

John A. Panning

Kirk Russell

Robert Savage

Jim Streufert

John Streufert

Jon H. Thieszen

Patrick Thieszen

Adam Ullerich

Sally J. Winter

Dean C. Zenor

From The Consultant

Ideally, the role of an organ consultant is minimal: educate a church to its own smart decision, then step back to let builder and client form their own good relationship. Inevitably some situations suggest a more active role, and St. Thomas Church has required a mix of historian, diplomat, advocate, apologist, and resource. At the time of this writing, it is 14 years since John Scott asked me to survey the Arents Organ, an assignment I accepted with excitement—working for John Scott and this great place—mixed with trepidation—admiring an institution is not the same as working for it. History can hang heavily at St. Thomas, eggshells always somewhere for the stepping on.

Like any good organ geek, I’d been visiting St. Thomas since my teen years, and had fully entered into the lore of the place, particularly G. Donald Harrison’s incomplete final statement. Harrison died suddenly in June 1956, while finishing Aeolian-Skinner’s rebuild of the existing organ (a Möller rebuild of the 1913 Skinner, which Skinner had occasionally altered beginning in the 1920s). For those of us who revere Harrison’s best work, that 1956 instrument is a great lost “what if,” tinctured by his untimely death. However, by the time of my first visit to St. Thomas in 1981, the organ had long since been transformed by ex-Aeolian-Skinner voicer Gilbert F. Adams, whose work was surely inspired by the mid-century “Cochereau” rebuild at Notre Dame in Paris. To my teen ears, it seemed a curious organ, an impression not much altered 25 years later when I spent a week surveying it. In between, on numerous occasions I’d attended services and heard Gerre Hancock reign at the console as only he could. But I had also turned pages for friends who were, or had been, assistants: the late Bradley Hull, Michael Kleinschmidt, Peter Berton, Brian Harlow, Fred Teardo. It was an education to watch these skilled musicians try to pare down the organ’s searing tutti into something that made sense for the weekly work of the place, the five sung services. It became clear, at least on one level, why Hancock programmed so much unaccompanied music: Adams’s organ had a range of foundation tone of surprising calmness, upon which that room worked a certain magic; a frustratingly ineffective Swell box (the only survivor of the two original Skinner swell boxes, now lacking one set of its original doubled shutters), and not even so much as a Clarinet, though one was eventually inserted in 1982. The effects that could work in a thrilling manner for swashbuckling repertoire were in direct competition with the church’s other star: the Choir of Men and Boys.

Surveying the organ in 2005, I suppose I was hoping to find G. Donald Harrison’s final testament still buried within, somehow recapturable. Instead I found an organ that had almost no 1913 Skinner pipes, a good amount of pipework from 1956, and much from the Adams rebuild of 1964–69. Surviving Aeolian-Skinner material was often altered, sometimes drastically; no single flue or reed chorus survived as Harrison would have known it; much of his upperwork had been replaced outright. Coupled to this was a mechanism surely troubled from the start. The Skinner and Aeolian-Skinner material was fine; it was Adams’s slider windchests in the Swell, Positiv, Vorwerk, and Grand-Choeur where the compromise came, built from a keen desire to avoid the leather of the 1960s that failed so swiftly. These chests were built too soon in the revival of such mechanisms to be done well. In the end, I felt sympathetic for Mr. Adams. To create an organ specifically for Romantic and modern music in the 1960s was daring stuff. What other organ of its day had five 8′ manual principals, three septièmes, this dramatic, cranky tutti? Even Harrison’s version hadn’t contained some of those things. But this was incomplete work at best, now hobbling along, despite the diligent ministrations of curator Larry Trupiano, and antagonistic to too much of what St. Thomas exists to offer.

I also found a church determined not to live in musical aspic, reliving only the high points of the Hancock era. John Scott was not Gerre, a fact he freely admitted. He hadn’t Gerre’s astonishing improvisational gift—who did?—but he was a perfectionist about choral tone production and repertoire interpretation, abilities he brought in abundance to St. Thomas. On some level, Gerre improvised because in the end, it’s what put the organ, and St. Thomas, in the best light. John wasn’t prepared to live with this large but limiting instrument. He wanted an organ that would lead the hymns more effectively, reaching more clearly into the nave, and accompany the choir not with the handful of registrations the Adams organ offered, but with a richness of variety he might still be uncovering a decade on. Finally, he wanted an organ whose breadth of capability matched his own catholic tastes in repertoire. But he said nothing of this to me, or to Yale University’s Joseph Dzeda, from whom he commissioned a simultaneous, independent report. John asked us simply for our carefully considered thoughts. The organ committee scheduled our final presentations for June 14, 2006, by coincidence the 50th anniversary of G. Donald Harrison’s death. (Intentionally or not, St. Thomas always has a knack for being St. Thomas.) Joe and I had reached the same conclusion: it was time for St. Thomas to begin anew.

The following year, I was brought on to guide the process of commissioning a new organ. Visiting instruments, inviting builders to propose, and choosing among three intelligent contenders evolved into the more arduous decisions: what to include, what to forego, how to fit it all in, and how to pay for it. But this describes every organ project. Easily the most challenging choice here was to eliminate the exposed pipework from 1956, now seen as a mid-century incongruence amid Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson’s neo-Gothic splendor, and to introduce a second case opposite Goodhue’s. At first the concept seemed unthinkable—too competitive, too daring, too new. When archival research revealed that the architects had initially proposed dual case-fronts, minds changed. The musical argument and John’s clout turned the unfathomable into the inevitable.

Like the design development of the building itself, the massing of the south case was worked out first. Lynn Dobson argued persuasively that the new should not merely duplicate the old; repeating that profile on the left would block too much view of the reredos. Instead, Dobson proposed an inverse plan, with a single central tower, and several inches shallower, preserving more views from the left than the existing case does from the right. With the form worked out, the process paused, thanks to the financial crisis of 2008, and revived in earnest with the engagement of the carvers and signing of the organ contract in 2014. In turn, these events coincided with the arrival of Canon Fr. Carl Turner as rector, who threw himself into design work with Lynn Dobson and lead carver Dennis O. Collier. Fr. Turner established a theme of “Music, Ministry, and Praise,” meticulously working out decorative content with Dobson, Collier, Wardens Kenneth Koen and William Wright, and committee co-chair Karl Saunders. Quality was the touchstone. This masterpiece church, containing some of the world’s finest Gothic revival art, commanded nothing less from anyone who would dare embellish it further. New tin pipes in the 1913 case-fronts, with different foot-to-body relationships, subtly revise the effect; new lighting on both cases allows us to appreciate the 1913 case as never before.

Being an adviser to this process has involved more than sharing knowledge, exposure, and opinion. It has entailed being a small part of a long, steady building of trust among parties, such that this church—in the face of some public opposition, financial obstacle, and artistic challenge—would find it more appealing to act boldly than to cower to sentiment and the tugging of the past. Key losses along the way have been difficult to absorb: Max Henderson-Begg in 2008 at only 46, verger and valuable member of the organ process; John Neiswanger, dynamic co-chair of the organ committee, in 2010, at a mere 61 from cancer; Irene Miller at 93 in 2018, wife of the organ’s principal donor, William R. Miller. The shock of John Scott’s death, at only 59, cuts as sharply today as when the phone call came in August 2015. I pray John would have found favor with this instrument, as it responds to so many interesting ideas he had, overarching aims of comprehensiveness, clarity, warmth, and color.

In that regard, this project found an ideal inheritor in Daniel Hyde. Dan, aided by Ben Sheen, dove in 110 percent with the voicing team and me, as the organ took shape, stop by stop, over the past year. His rousing recital on October 5, to an audience of 1,100, opened a weekend of festivities, including the organ’s formal dedication at the Sunday Mass to the Langlais Messe solennelle, and music of Candlyn, Hancock, and Scott, among others.

While every organ project requires calm and confidence to see it through, this effort has required uncommon bravery to rise to the standards of the edifice and expectations at the highest levels. Lynn Dobson, John Panning, and their team, together with the Colliers and their staff, were materially supported by two rectors (Fr. Andrew Mead, Fr. Carl Turner), two tireless committee co-chairs (Kenneth Koen, Karl Saunders), the entire music staff, including the marvelous Laurel Scarozza (music office manager), the ever-helpful Lawrence Trupiano (organ curator), unstoppable Angel Estrada (facilities manager), and unflappable Barbara Pettus (director of administration and finance). This was a church at its best: supple when necessary, stalwart when it counted most. The result speaks for itself.

Jonathan Ambrosino

Centenary of the Founding of St. Thomas Choir School

The yearlong celebration of the new Miller-Scott Organ coincides with another milestone of the parish: the centenary of the St. Thomas Choir School. Founded in 1919 at the urging of T. Tertius Noble, the School came about through the generosity of Charles Steele, a railway lawyer and associate of financier J.P. Morgan. Steele gave two houses on West 55th Street and had them overhauled for their new purpose. Before the 1920s closed, Steele donated further funds to secure the School’s future.

A great achievement in the rectorate of Fr. John G.B. Andrew and tenure of Gerre Hancock was the opening of the new Choir School, at 202 West 58th Street, a 14-story building comprehensively equipped for its purpose. St. Thomas’s remains the only residential boy choir in the United States.

Now, a century later, it seems the most countercultural proposition to send a nine-year-old boy not only to a boarding school, but a boarding choir school, in the wiles of Midtown Manhattan. The notion seems to go against every grain of modern parenting. And yet, consider what this experience does for a serious-minded boy at a critical age:

• first-class education in a tutorial-like atmosphere of intimate class size;

• intense musical training and focus with superb musicians;

• early exposure in foreign languages, some taught in the context of musical study;

• a tight community built around the team-building of daily service;

• developing an independent mind and spirit;

• an excellent dining room (or so we are told!).

Given the sense of mission and independent spirit the school attempts to foster, it may seem inevitable that alumni continue musical pursuits. A prominent example is Dana Marsh (’79), who went on to several church positions involving boys’ choirs, and is now at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music as chair of the Early Music Department and director of the school’s Historical Performance Institute. In addition, he was recently named artistic director of the Washington Bach Consort.

Another well-known alum is Julian Wachner (’83), director of music and arts at New York’s famous Trinity Church Wall Street. His facility at improvisation is a direct result of his years at St. Thomas Choir School, observing and working with Gerre Hancock. Active as composer, conductor, and organist, Wachner’s activities at Trinity and elsewhere have brought considerable musical renewal to Lower Manhattan. He also teaches at General Seminary, where he lives with his wife, the Rev. Emily Wachner.

Sometimes the intersection is strongly musical, but less clear-cut. Martin Near (’93), son of an Episcopal priest, attended a choir camp in Akron, Ohio, led by Gerre Hancock. “A loud Möller organ made an impression on ten-year-old me,” Near recalls. “And Uncle Gerre called me ‘Harry’ because he couldn’t always remember my name! But, within a few weeks, I was at the school.” Four years later Hancock asked Near to compose a setting for “God Be in My Head” for the final service of the 1993 school year. For the remainder of Hancock’s tenure at St. Thomas, that anthem was traditionally sung at that service.

Near’s career since has involved plentiful singing in the Boston area as a countertenor, both at the Parish of All Saints, Ashmont, and Church of the Advent. He is a member of Blue Heron, the innovative and prestigious early music ensemble that just won Gramophone’s Classical Music Award for Early Music. But in his other life, also stemming from early exposure at St. Thomas, Near has become a pipe organ restorer. Working with Spencer Organ Company of Waltham, Mass., Near specializes in the restoration of the thousands of individual pipes that form the “choir” of an organ.

In other cases, the link between school and career may seem indirect, but is no less significant. Thomas Carroll, MD (’88), is director of the voice program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, where he serves as a laryngeal surgeon. Additionally, he is an assistant professor of otolaryngology (ear, nose, and throat) at Harvard University School of Medicine. “I never saw myself as a professional musician,” he says, “but through the education, independent spirit, and work ethic instilled at St. Thomas, I pursued a profession that allows me to use my knowledge of music and voice in a field that cares for professional voice users.”

In yet other cases, the link couldn’t be clearer. The Rev. Sean Mullen (’84) is rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, where he also serves as president of the board of St. James School in Philadelphia, of which he is also a cofounder. As a graduate of St. Thomas Choir School in New York City, Fr. Mullen writes about the benefits of a small, Episcopal middle school in the heart of an urban city:

Few of my classmates came from families that would have had access to the education and experiences we were given at St. Thomas Choir School. It was at St. Thomas we learned not only all the usual school subjects and the lessons that came from a demanding musical training, but also—and perhaps more importantly—we learned that God loved us, and that we had gifts to offer, nurtured by the church, that were a delight to God and to God’s people. We learned that we could achieve incredibly high standards when we concentrated, worked hard, and used the gifts that God gave us.

And naturally, some graduates’ lives head in far different directions. Sean McFate (’84) is an author, novelist, and expert in both foreign policy and national security strategy, teaching that subject both at the National Defense University and Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. His acclaimed books explore both the history and future of warfare into the 21st century.

The centennial year has a number of special events (Choirschool.org), including the March 3 Founders Day Reception and Lunch and the June 8 100th Commencement Ceremonies and Prize Day. A feature of this year’s organ celebrations is the return of former assistant organists for Sunday recitals, but some recitalists will also be Choir School alumni, including Marsh and Wachner. Finally, alumni who have taken holy orders have been invited to preach Evensong sermons, including the Bishop of New Jersey, The Right Rev. William “Chip” Stokes (’71) on March 31.

As the Choir School heads into its second century with a renovated facility, it has a revitalized commitment to serving Church and community through this remarkable form of education. Keep the school in mind the next time you meet a boy of independent spirit.

Susan Hill

Jonathan Ambrosino

Two Tales of Two-Manual Organs

Two Tales of Two-Manual Organs

St. Paul’s Memorial United Methodist Church

St. Paul’s Memorial United Methodist Church

Multum in Parvo

Multum in Parvo

Northrop Auditorium and its Reconditioned Aeolian-Skinner

Northrop Auditorium and its Reconditioned Aeolian-Skinner

Sewickley Presbyterian Church

Sewickley Presbyterian Church During the academic year, traditional worship services are conducted in the chapel each Sunday. A small group of singers or an instrumental soloist joins the organist in the balcony from time to time. The chapel is also used for small

During the academic year, traditional worship services are conducted in the chapel each Sunday. A small group of singers or an instrumental soloist joins the organist in the balcony from time to time. The chapel is also used for small