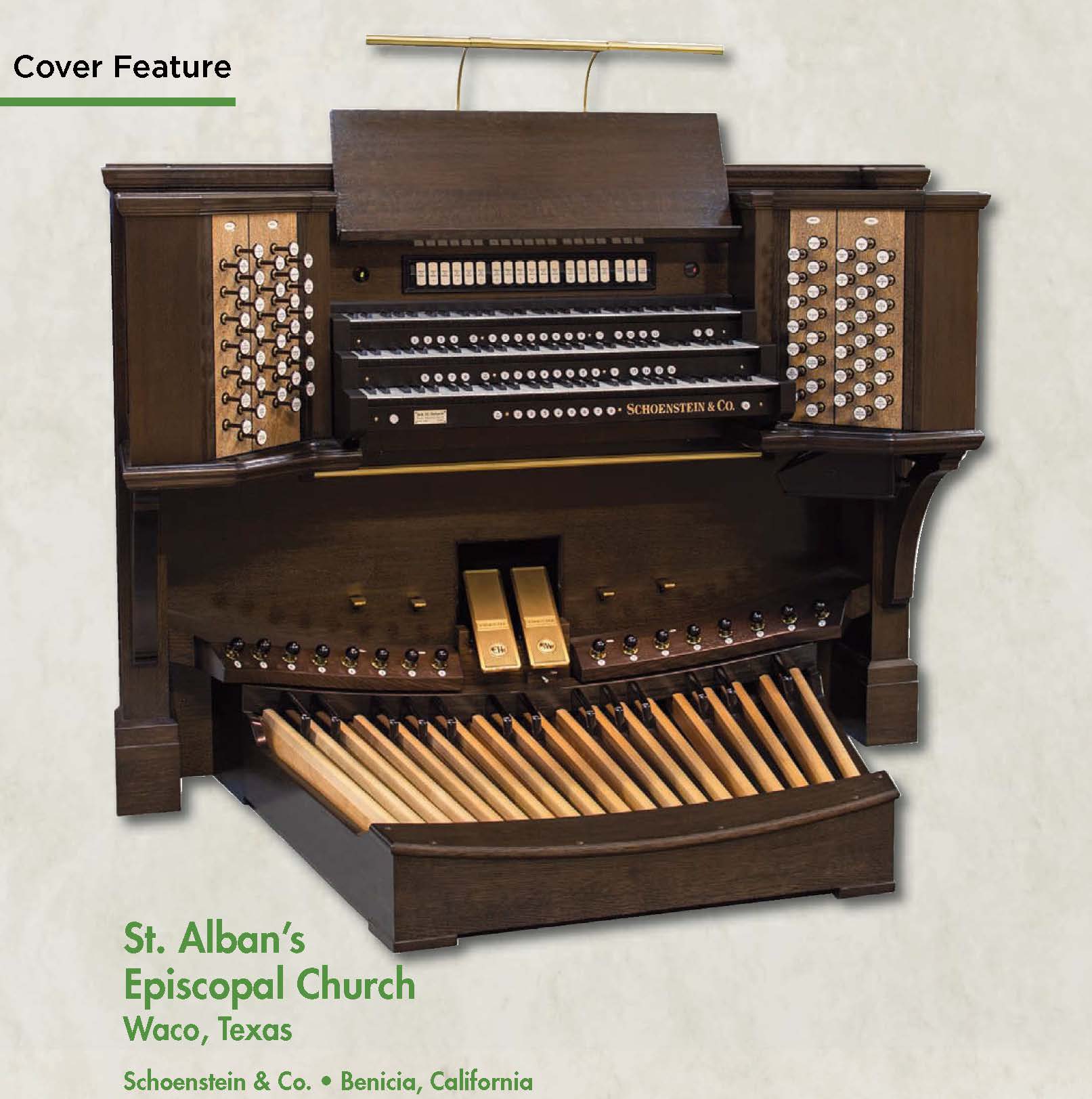

St. Alban’s Episcopal Church

Waco, Texas

Schoenstein & Co.

Benicia, California

Stoplist

by Jack M. Bethards

I was asked by Eugene Lavery, organist and director of music at St. Alban’s Episcopal Church, Waco, Tex., to write a note to the parish explaining the design of its new organ in terms anyone could understand. St. Alban’s is an extraordinarily fast-growing church with many parishioners who are new to Anglican liturgy and music. The music program is a major part of parish life, and the newcomers are eager to learn about this organ—why it seems so complicated, took so long to build, and cost so much money! Although TAO readers already know the answers to these questions, I thought this primer might be useful as a handout, to answer questions from people fascinated but baffled by the pipe organ.

Our Organ—One of a Kind

The easiest way to understand the pipe organ is to think of it as a kind of orchestra—a group of wind instruments under the control of a musician who directs them with keyboards rather than a baton. Each instrument of the organ is called a voice (or stop). Therefore, this organ of 27 voices is like a 27-piece orchestra. As in an orchestra, each type of instrument has a different tone color. Violins, flutes, oboes, and trumpets have distinctly different tones but often play together as an ensemble. The same is true of the organ. Most of its tones are related to tones of the orchestra, but the instrument has one that is unique in the world of sound—the diapason. Diapason means normal—the normal tone of the pipe organ. This is the sound you expect in a hymn. In designing the St. Alban’s organ, our first concern was having a solid foundation of this pure organ tone. The instrument has 14 diapason-type stops, half of the total voices in the organ. It also has five stops in the flute family, two of violin tone, three woodwinds, and three brass. You will note that each of the voices is preceded by a number, which shows the length of the lowest pipe. The number 8 indicates piano pitch (the length of a grand piano is approximately eight feet). The 16′ is twice as low, 4′ is twice as high, and so on. This is something like the string section of an orchestra, where the double bass is a 16′ instrument, the cello is 8′, and the viola 4′.

How did we go about selecting the voices? The first consideration was the music program. St. Alban’s has a serious Anglican-style program, with a fine choir performing the great Anglican repertoire. The organ is designed strictly with this in mind and follows in the steps of the 19th-century Anglican reform in England, wherein parish churches aimed for cathedral-quality music—and organs of the same caliber. The most important factor in delivering appropriate accompaniments is variety of tone color and of loudness. Color variety is produced by the different types and pitches of diapason tone, as well as voices imitating violin, flute, oboe, clarinet, trombone, trumpet, and horn. Also on the St. Alban’s stoplist is the Vox Humana, which gives the effect of a choir heard from a great distance.

This type of organ and the required playing technique are called “symphonic.” The organist has a far bigger job than just playing the keys. He must also take the role of orchestrator. In a symphonic composition, all of the decisions about what instrument plays at which point are determined in the written score. Developing such a score is the art of orchestration. The organist has no such score—only a basic sketch that looks like piano music. The organist has to make all of the decisions on which voices to use and how loud or soft they should be. Variety of loudness is achieved by selecting voices of different basic loudness and further controlling the volume with an expression box fronted by louvers that open and close at the touch of a foot pedal. Playing in the symphonic style is a daunting task involving the keyboard technique of a concert pianist and the dexterity of a surgeon, combined with the interpretive genius of a fine conductor and the musical knowledge of a skilled orchestrator. And in the Anglican tradition, the organist must at the same time be a choirmaster!

Balancing the number and type of stops to the music program is the first challenge of organ design and is much like selecting orchestra players; however, the organ is a permanent, built-in part of the church. With an orchestra, you can change personnel if things don’t work out, but an organ has to be a perfect match to the acoustics of the building. That’s where the art of scaling comes in. Scale, in simple terms, is the diameter of the pipe. A giant cathedral requires pipes of a larger diameter than does a village church. We bring actual organ pipes of various scales and test them in the church to determine a scaling system. All pipes are then custom built to fit the acoustics of the building. In the case of St. Alban’s, we suggested some acoustical improvements, and the parish engaged one of the nation’s foremost acoustical engineers, Paul Scarbrough of Akustiks LLC, to develop a program to improve the transmission of sound from the chancel to the west end of the nave, and to increase the reverberation time—how long sound stays in the air after its production has ended. The main improvements were installing a beautiful new tile floor and plastering the side walls. We are very grateful for these changes because they did a lot to enhance the beauty of the organ’s tone. We also located some of the instrument’s voices in the gallery. Even a fairly soft tone playing along with the main organ in the chancel will aid in clarifying the melody and rhythm in hymn singing. The gallery stops can also be used for accompaniment of children’s choirs and other small ensembles.

We were privileged to serve St. Alban’s—a healthy, growing parish with the highest standards in liturgy and music. We were blessed with a thoroughly professional and hardworking team, under the leadership of Rev. Aaron M.G. Zimmerman, which made our installation work a pleasure. Florence Scattergood was dedicated and effective as project manager, and Eugene Lavery provided the musical inspiration for our work, offering important suggestions on the selection of voices for the organ, providing musical guidance to us throughout the project, and showing our work so beautifully every time he approaches the console.

The organ was dedicated on August 28, 2022, a day that culminated in a brilliant recital by Bradley Hunter Welch, a Phillip Truckenbrod artist and the resident organist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. The recital was also a homecoming of sorts, as Welch was organist at St. Alban’s from 1993 to 1997, while he was a student at Baylor. His beautifully balanced program fully explored the organ’s resources. The enthusiasm was so great that two large meeting rooms were needed for overflow video viewing.

Jack M. Bethards

President and Tonal Director

Schoenstein & Co.

Photography: Louis Patterson