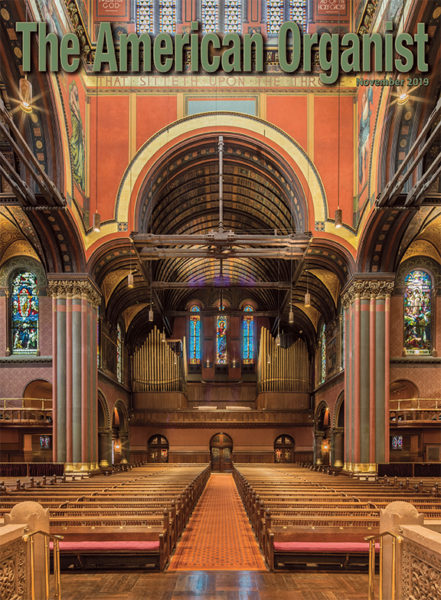

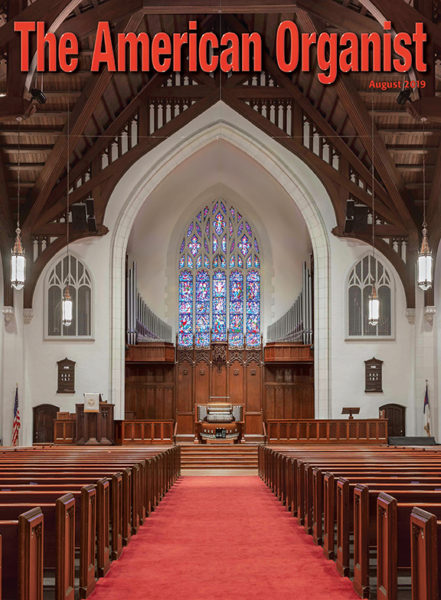

Basilica of the National Shrine of Mary, Queen of the Universe

Orlando, Florida

Schoenstein & Co.• Benicia, California

View the Stop List

The Tonal Perspective

The tonal design opportunity here was truly grand—plenty of well-placed space for each division and a stoplist large enough to face no compromises. The challenge, as always, was making a good acoustical match. Even a “perfect” acoustic must be carefully matched to make full use of its quality. The Basilica is built on the plan of the original fourth-century St. Peter’s in Rome, but, of course, it is made of modern materials. The size and shape encourage a wonderful openness and short, but pleasing, reverberation. The clarity is quite wonderful. The frequency response favors the upper middle range rather than low bass and the very top end. The result is a perfect transmission of the overtones, producing an astonishing array of color. Here is an experienced voicer’s look at how we took advantage of the situation.

J.M.B.

The commission for a new organ for the Basilica of the National Shrine of Mary, Queen of the Universe, presented a unique challenge. The Shrine is a place of pilgrimage. Orlando draws people from the world over who seek rest, entertainment, and spiritual renewal. Roman Catholic pilgrims from far and near visit the shrine daily to pray, attend Mass, and receive the Sacraments.

As designers of any new organ, we seek the answers to many questions: What does the client want? What will the organ be used for? What are the acoustical properties of the room?

The client requested an organ that was grand in scale—befitting the scale of the Shrine. They also requested an organ that would set the spiritual tone in the building, complementing the existing stained glass and visual art. This goal was to be reached when accompanying a professional choir or the congregation, upholding the pageantry of any ceremony held within the building, and contributing to a major concert series. With these commission requirements, it was up to us to make the vision come alive within the acoustics of the room.

The interior is very large. It is a new building constructed of modern materials producing a “modern” acoustic. The bass and tenor frequencies are muted, but the soprano frequencies are enhanced. Also, the professional choir is amplified such that the acoustical presence of the organ has to compete with the sound system, which has speakers everywhere. To be able to fill its mandate, the organ needed substantial sonic resources placed at both ends of the building and had to be capable of producing vast but subtle color effects.

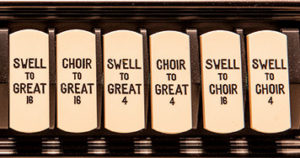

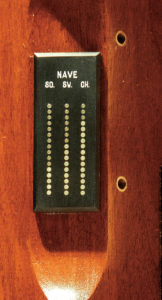

The main organ sits behind the altar and is divided by the tabernacle. It consists of the Great, Choir, and Swell divisions on the left and the Solo and enclosed Pedal on the right. Far to the left and next to the choir loft is the Positive, which provides pitch and rhythm to the singers. At the nave entrance, and 30 feet above, is the Gallery organ. This arrangement surrounds the congregation with sound that is musically controlled by six expression boxes over five divisions. The organist presides over all of this at the console, located near the choir loft.

The tonal possibilities available to the organist are vast. If you read through the stoplist, the standard requirements for organ literature are included and do not need to be pointed out. However, the unusual stops are well worth your time. For example, the “horn” tone can be graduated through steps—look at the list. Strings from a whisper to a waterfall are available. Need a Diapason to balance your accompaniment? Make a selection. Trumpet soft, loud, mournful, triumphant? Pick one. Both of the powerful solo trumpets are under expression.

A vast color palette at a mezzo forte level is what this room demands acoustically. Otherwise the listener would soon tire of the organ. Consider again the resources available to the musician: 6 expression boxes over 5 divisions that control 12 ranks of diapasons, 13 ranks of flutes, 13 ranks of strings, 8 color reeds, and 8 ranks of trumpets. On top of this are 6 ranks of independent flute mutations and 17 ranks of diapason upperwork. All of this is cleverly made available at additional pitches and independent draws, assuring that all the organ’s color is available for any combination the organist can dream up. The organ is an acoustic synthesizer with the console acting as its mixing board.

And this is just what this building needs and what the client requested: to fill this vast room with ever-changing sound that surrounds the listeners, accompanying them on their spiritual journey.

Timothy Fink

Voicer

Schoenstein & Co.

The special challenge for casework design in the Basilica was the tension between size and simplicity. The building is huge but not elaborately decorated. The goal was to make it seem the organ was there from the beginning. The case could not be dominant or “busy.” A simple array of 32′ pipes at the east end and 16′ pipes at the west would be in proportion to the size of the space, but how could it be made into more than a “picket fence”? That was the challenge to be met by the design team. Glen Brasel, our design director, tells how.

J.M.B.

Designing and building the casework for a pipe organ involves many variables. Some to consider are the architecture of the room, the available space for casework, which pipes will work in display, the budget, and the firm to produce the casework. While sorting out these issues one must also consider who will be involved in the approval process.

The initial design of the organ mostly involves the stoplist and the behind-the-scenes working space for the organ. This step in the process is usually carried out with just the organist-music director, but once the casework is being considered many more people are involved. Whereas most members of a church are happy to leave the technical design to the music professionals, it is a sure thing that they will have an opinion about how the organ casework looks! A committee is usually involved, as well as an architect to provide professional assistance.

On this job we were fortunate to have a lot of these variables fall into place early on:

• Although there wasn’t space planned specifically for the casework when the church was designed, ample space was provided for an organ.

• Pipes were not made until after the casework was designed so that we could select and specify the pipes needed in display.

• The church formed a committee of knowledgeable people from different backgrounds who were all able to contribute to the process.

• Fortunately, the project architects were Jackson & Ryan, a firm we had worked with before and knew would be up to the challenge of this very prestigious contract.

• Upon our recommendation, they hired New Holland Church Furniture to build the casework. This is another firm we have worked together with on multiple projects and never hesitate to recommend, knowing we can always depend on their integrity and craftsmanship.

With all these parts in place, the process was very smooth. Cameron Bird, brilliant designer from Jackson & Ryan, generated preliminary sketches showing a wide variety of architectural styles for the committee to consider. Once the committee approved the visual concept, I went to work with Cameron to fit the specific pipes into the casework openings and finalize the dimensions and proportions of the millwork.

Under the leadership of New Holland project manager Mike Zvitkovich, shop drawings were produced. Just like the design phase, this involves a lot of back-and-forth to get all the construction details ironed out. From these shop drawings, New Holland was finally ready to go to work building the massive main casework and the intricately detailed gallery casework with all of its overlapping angled supports.

The compliment we most appreciated was from a regular Shrine worshiper: “It seems so natural, I can’t remember what the Basilica looked like before.”

Glen Brasel

Design Director

Schoenstein & Co.

Reaching the Goal

This grand organ is the largest we have ever built for a Roman Catholic church in our 143-year history. It has very special meaning for our firm and our founding family. Surely our founder, Felix F. Schoenstein, a devout Catholic who dedicated two children and two grandchildren to Catholic religious orders and built his very first organ for a Marian church, would be pleased. Having emigrated from Germany, he would be especially honored to know the organ will be serving an international assembly from among the 75 million who visit Orlando yearly.

A grand pipe organ has been the goal of the Shrine since the Basilica was built in 1993. It has been the inspiring leadership of the Very Reverend Paul J. Henry, rector, that made it a reality with the help of major donor Nick A. Caporella and others. Sometimes large projects can get bound up in bureaucracy, but Fr. Henry and his dedicated professional staff have always made us feel at home, helping us at every turn. Gina Schwiegerath, Bryan Weeks, Lisa Nordstrom, Vince Castellano, and their professional and volunteer helpers were vital to the operation of our work on-site. The outside contractors preparing the site were under the direction of project manager Mark Rieker. The Diocese of Orlando was represented by Darryl Podunavac. Finally, my personal thanks to the organbuilders of Schoenstein & Co., who did all the heavy lifting.

Jack M. Bethards

President and Tonal Director

Schoenstein & Co.

Photography: Louis Patterson and Henry Baron