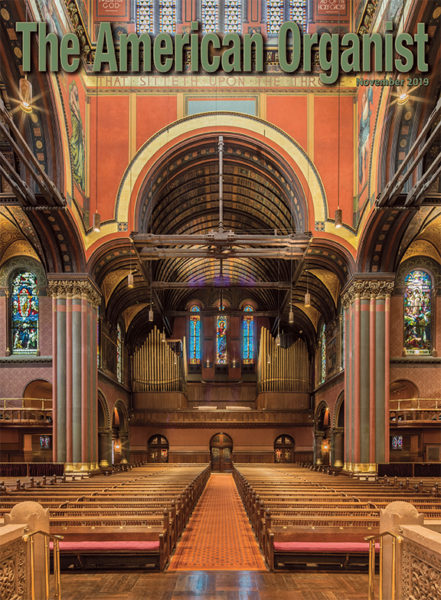

Trinity Church in the City of Boston

Skinner Organ Company

Boston, Massachusetts

Opus 573 — 1926

Nave Organ Tonal Reconstruction

Jonathan Ambrosino and Foley-Baker Inc.

New Console

Richard S. Houghten and J. Zamberlan & Co.

View the Stop List Original Specification

View the Current Stop List Page 1

View the Current Stop List Page 2

by Jonathan Ambrosino

Background

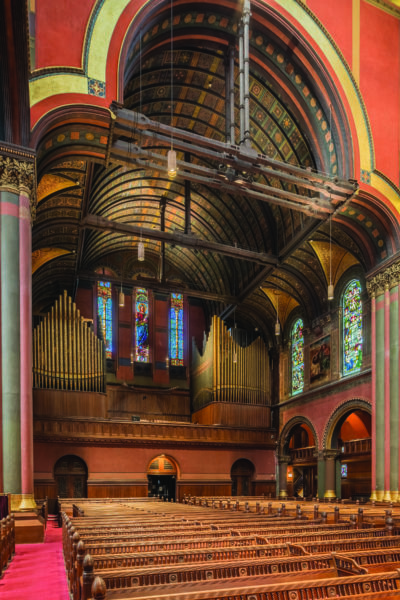

H.H. Richardson’s Trinity Church of 1877 was a one-building revolution in architecture. Hilborne Roosevelt’s Opus 29 aimed similarly high, being the niftiest bit of organ technology to arrive in Boston since the 1863 Music Hall Walcker. Stretching five stories, from basement water motors to attic Echo, this New York–built organ should have been an auspicious launch into a Boston market dominated by Hook & Hastings, Hutchings, and Johnson. But, unanticipatedly stifled in its chancel chamber, Roosevelt’s organ made distressingly little impact. Trinity’s rector, Phillips Brooks, had a one-manual Hook & Hastings installed in the nave gallery, to test that location; Brooks paid for it himself, since the vestry wouldn’t. Buoyed by the little organ’s effectiveness, the vestry acceded, and had the Roosevelt moved there in 1881, by Hutchings (perhaps smirking with schadenfreude).

For the next four decades, Trinity’s organs were a carousel of taste and trend: updates to the nave organ, a 1902 chancel organ to accompany a new choir of men and boys, electric action in 1904 joining everything together. Inevitably, Ernest Skinner arrived on the scene, furnishing an imposingly tall four-manual console (Opus 479) in 1924, and then a new four-manual, 54-stop nave organ (Opus 573) in 1926. Francis Snow, Trinity’s French-educated organist, had chaste registrational tastes, and his stoplist may have been telegraphing either classical desires or anti-ponderous hopes. The Great had a full chorus with three opens but no open double; the Pedal had both metal and wood open 16′ s. Further novelties included two Swell oboes, bright and dark, an absence of large flutes, and an uncommon Choir 8′ Trumpet. The record is largely silent on this organ’s success, save this from Louis Vierne, who played it in 1927:

Not a day passes that I don’t dream about your magnificent instruments I played over there; their marvelous touch, their fine tone, their perfect and sensitive action haunt me. It seems as though I were dreaming when I think of Trinity Church, Boston, of St. John’s, Los Angeles, Hollywood High School, Williamstown, and Utica.

Was Snow as captivated? By 1931 he had had a few changes made, and in 1938 yet more, now from Ernest M. Skinner & Son: lean Choir Trumpet, Pedal upperwork, lighter-toned Pedal reed with 32′ Fagotto bass. (Skinner happily reused the 1926 wood Bombarde at Washington Cathedral, where, considerably altered, it remains.) Far greater change was yet to come.

The Faxon Era

In the mid-20th century, Boston had no more influential or well-rounded organist than George Faxon: student of Albert Snow (Emmanuel Church, Boston), Harold Darke, and Carl Dolmetsch; trumpet player, organ professor, jazz aficionado. He served Church of the Advent and St. Paul’s Cathedral before coming to Trinity in 1954, and by his retirement in 1980 had transformed Trinity’s organs. It began in 1956 with a new Aeolian-Skinner console, purposely three manuals and as compact as the old one was towering. Novelties included most strings and celestes on single knobs that, drawn halfway, produced the first rank only; a sostenuto; second-touch manual pistons for discrete Pedal combinations; and a split cancel piston, retiring nave or chancel independently.

Through the 1960s, Faxon addressed the organ’s sound. His sensibilities lay along American Classic lines, and though to the best of anyone’s knowledge G. Donald Harrison never touched a pipe at Trinity, it is Harrison’s ethos Faxon pursued. Skinner-trained tuner-technician Jason McKown carried out this work, in cooperation with Aeolian-Skinner. Changes in the nave between 1961 and 1967 used some new Aeolian-Skinner pipes, several existing ranks, and a few recycled stops from the 1902 chancel instrument. In 1963, Aeolian-Skinner installed a new all-enclosed chancel organ. Eventually, it too received the McKown touch: certain mixtures lowered in pitch, prominent chiff curtailed. Dissatisfied with the 32′ Bourdon Skinner had retained from the Roosevelt, Theodore Parker Ferris, Trinity’s rector from 1942 to 1972, donated a new, larger-scaled one in 1967, provided by Aeolian-Skinner.

From chancel to nave, subtlety was the keynote: a fine mesh of mild choruses and unaggressive reeds, blend above all. In the late 1970s, Trinity’s organ was a staple of my teenage Sunday evenings, turning pages while Frederick MacArthur or Thomas Murray fashioned grand oratorio accompaniments. Thomas Murray made his first all-transcription recording here in 1981. It was a fine instrument with a beautiful spread and many magical effects.

So . . . what happened? For one thing, the carousel of taste and trend spun ’round again. The 1979 Prayer Book and 1982 Hymnal suggested increased levels of congregational participation, and with them perhaps a new kind of relationship among choir, organ, and congregation. Various tonal changes after 1980, during the tenure of Ronald Arnatt, achieved an increase in power, at a cost of musical sense. The Great chorus, always mild, now cowered beneath a raging Swell. In its Faxon iteration, the organ could be registered with aplomb. Now, it sounded best when played by those such as Brian Jones or Ross Wood, who knew what to leave off.

A New Vision

When Richard Webster arrived at Trinity in 2005 to work alongside Director of Music Michael Kleinschmidt, he found a congregation Brian Jones had trained to sing heartily, but an organ that struggled to lead them rewardingly: lean Pedal, light unison, aggressive chorus reeds, Skinner’s orchestral colors muted and unrepresentative. In 2010, Richard succeeded Michael as Director of Music, and gradually developed a vision informed by his 30 years at St. Luke’s in Evanston, with its famous 1921 Skinner. In short, could Trinity get its 1926 Skinner back?

The issue was not mechanical. Trinity’s organs have always been well cared for, notably during the 17 years of Foley-Baker’s curatorship with full renovations of nave (1999–2001) and chancel (2007). But apart from the usual reconditioning, a few new windchests made necessary by water damage, and some spurious digital voices, the organ’s musical imbalances went unaddressed. Certainly a Skinner ideal could work here, a sonic profile that resembles, in its way, the appearance and sound of the building itself. Without firm principles, though, any project could devolve into sentimental kitsch: another twirl of the carousel. Furthermore, it was important to remember the breadth of offering here. The four Sunday services are considerably varied in style; dozens of guest organists filter through every year for a popular Friday recital series; conventions involving choirs or organs invariably come here. As yet unchanged, the chancel organ is the primary vehicle for choral accompaniment, leaving hymns and repertoire to the nave. Therefore, any revision to the nave organ’s tonal palette needed to foster seriousness of ensemble as well as beauty of tone if it were to earn its place among Boston’s showcase instruments.

Still, the most intriguing path to recreating a Skinner flavor would be to use pipes built and voiced in Skinner’s shops. Primed by the availability of ranks gathered by Nelson Barden but ultimately unused for his project at the Community of Jesus in Orleans, Massachusetts, I initiated talks with Richard Webster in 2011. Mike Foley was quickly folded into the discussions, and a collaborative project planned. Together, Foley-Baker and I have a long history with Trinity’s organs: they as curators and rebuilders from 1997 to 2014, I from younger years and, now, as curator since 2014 and project overseer.

Reconstruction is the proper term here, where only 27 of the original 54 stops survive. It isn’t a typical rebuild, in which one person’s philosophy guides the recasting. Nor is it truly restorative in nature, since the instrument isn’t being returned to any specific prior state. The concept of “restoring” an organ using vintage pipes is itself a bit dubious, for it supposes that stops from the same builder are interchangeable. In truth, certain Skinner registers are stock voices: softer flutes, routine strings, echo voices, orchestral reeds. But the chorus elements, specially scaled for each organ, were always individual. As we gathered pipework over a number of years, the original scaling was borne in mind, and stops along those lines sought wherever possible. And in the background, I had to reconcile this new vision with a lingering fondness for certain aspects of the organ’s Faxon-era iteration, in particular the 1960s Swell reed-and-mixture chorus. That department once had a marvelous restrained fire, enjoying kinship with the iconic Swell at Boston’s Church of the Advent. In its original, then exaggerated, form, that tone had been part of the Trinity sound for half a century—something congregations and hundreds of guest organists had known. It seemed wrong to eliminate that quality altogether.

In the end, those charged with such a project must accept two realities. First, one can only acquire what is available and fashion a result suiting that material. Second, only Skinner himself sitting at the console could recreate his own work. Those involved today cannot act as clairvoyants channeling the dead. Instead, they must rely upon their own good sense and experience, and take ownership of the outcome.

The New Console

After 60 years of playing and a few partial renovations, George Faxon’s 1956 console was worn out. Moreover, its rationale for compactness now seemed outmoded, with an established pattern of two musicians, not a lone organist conducting from the bench. It was time once again for this four-manual organ to enjoy a four-manual console. There was no question to whom Trinity would turn for this piece of the project: Richard Houghten, with his now customary support from the shop of J. Zamberlan & Co. Once president of what was then Solid State Logic Inc., Dick has been responsible for some of our era’s most beautiful and forward-thinking consoles, usually in the Skinner or Aeolian-Skinner mode, most in collaboration with the talented builder Joseph Zamberlan. This team provided the new console at Duke University when Foley-Baker rebuilt the 1932 Aeolian there, and the renovated Aeolian-Skinner console for Harvard University’s relocated 1930 Skinner.

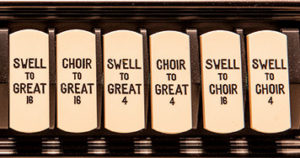

Trinity’s new console is fashioned from white oak with a walnut interior, placed on a mobile platform with elegant oak flooring, edged in solid brass. Several features combine retrospective detailing with the latest technology:

• Cabinet particulars follow design details in H. H. Richardson’s 1877 chancel furnishings.

• Knobs and pistons of reduced size, together with drop-sill construction and no rolltop, allow comfort without undue height.

• The keyboards, with solid ebony sharps and bone-covered naturals, have a mild tracker touch. A principal goal was to eliminate wiping contacts wherever possible. Thus, key movements are sensed by Espressivo, a solid-state system that allows different attack and release points to optimize repetition, while not affecting key touch in any way.

•Similarly, Hall Effect thumb piston sensors by Arpad Muryani will never suffer contact failure. Walker sensors in the pedalboard and swell shoes function similarly.

• An expression matrix assigns the six shutter fronts to any or all of the four balanced pedals. The matrix has its own divisionals, and can be set on generals if desired. As a bonus, the chancel transept shutters can now operate independently.

The entire complement of SSOS features is incorporated here:

• Organist’s Palette (with sequencer customizing, adjustable pedal divide, and other functions) is supplemented with a few refinements. For flexibility, All Pistons Next is separated into All Generals Next and All Divisionals Next. Go To permits direct access to any memory level, by entering its number via general pistons.

• The wireless Tuning for MultiSystem allows a single technician, via an iPod, to set temperaments and key quickly through any combination of stops. We use this device constantly—cleaning magnets, adjusting valves, blowing out chests, adjusting swell engines, installing pipes—all without needing someone at the console.

• Recorder for MultiSystem, controlled either at a console panel or remotely via the iPod, allows registration and balances to be evaluated away from the console. On one organist Sundays, the musicians sometimes record short snippets to give pitches so they don’t have to leave the podium.

• Voicing for MultiSystem has a full keyboard and stop control via wireless laptop. Taking this rig anywhere in the building is convenience incarnate for tonal finishing.

The Houghten-Zamberlan attention to detail is pervasive. Beyond all his fine design work and cabinetry, Joseph discovered Garolite, a material visually akin to Bakelite, which was used for the indicator bezels, bench height indicator, and expression matrix. In addition to his usual meticulous interior finishing, Dick used tiny LEDs for the shutter indicators, and non-distracting lighted buttons for the expression matrix. The console has individual power supplies for all lamps and indicators, each separately dimmable so that illumination can be finely adjusted.

Perhaps the greatest homage to Skinner comes in the digitized approximation of the hand engraving found on his consoles. High-resolution photography at Yale University’s 1929 Skinner console, by Zachary Ventrella of the A. Thompson-Allen Co., formed the basis for a font by Los Angeles graphic artist Jack Foster. Multiple variables for every letter and number, further customized in Adobe InDesign (slanting, fattening, slimming), permit myriad subtle variations between adjacent examples of the same character, as one finds in the original hand engraving. Gene Ladenes at Harris Precision Products deserves special thanks for his many hours working with us to get everything exactly right.

The Tonal Work

The present specification mostly follows the 1926 one, with a few departures:

GREAT: When the Roosevelt was moved in 1881, its green-stenciled facades went with it. They stand opposite one another across the gallery, supplemented with gold pipes facing east. In 1926, Skinner used only the north facade for the Pedal 16′ Second Diapason. We wanted a 16′ open beneath the three Great Diapasons, so it seemed logical to reactivate the north facade as the bass, paired to a Skinner treble. Foley-Baker made it all work mechanically (action box and tubing for the facade, new treble chest alongside the main Great); we provided treble pipes and adjusted the facade voicing. With no available vintage replacement for the Doppel Flute, a typical Skinner Claribel takes that position.

The chorus is made of registers from 1921 to 1934, mated as closely as possible to the 1926 chorus’s scaling. With so much material from 1927 to 1934, however, the effect is surely brighter than the original, with stronger melodic emphasis and keener trebles. One hundred eleven pipes of the original Mixture survived, dispersed among five registers of the Faxon era. The originals were inventoried, any cut-down pipes lengthened, and new fill-ins made by Jerome B. Meyer & Sons. The effect is convincing, and still telling above the powerful reconstituted reed chorus. The original Clarion is joined to replicated Tromba and Ophicleide ranks, made by Shires in England to the original scales.

SWELL: Stoplist differences between 1926 and 2019 are: a second mixture in place of the Clarabella, two trumpets instead of the oboe pair, and a principal-toned 2′ Flautino instead of the original Piccolo. The primary chorus, 8-4-2-III, is made of Skinner sets from 1919 to 1931. Like the Great, the effect has a keenness and sparkle, particularly given the silvery quality of the small-scale 1931 Mixture III. The Chorus Mixture IV is the 1961 Aeolian-Skinner tin Fourniture. It was always excellent, and needed only a bit of strengthening to shine through this new reed quartet. The Posaune and Cornopean (1939 and 1923 ranks, respectively) are the familiar burnt caramel, which pair logically to the Mixture III for ordinary use. The 1961 Trumpet and Clarion, with small-scale resonators and French shallots, are now in their third voicing, perky but not vulgar. Suppressing the Cornopean and adding all the upperwork produces a full Swell with something of the Faxon flavor. Retiring the Trumpet, Clarion, and Chorus Mixture IV evokes the older type of Skinner Swell. With everything drawn, it’s a powerhouse. Supporting voices have been regulated along conventional lines, in some instances being strengthened after Faxon-era calming.

CHOIR: This department has two departures from 1926. First, the crisp 1960s 8′ Viola remains, in place of the original Dulciana. With the Erzähler ranks now separately available, there seemed little point in having two echo-type unisons. The Skinner-replica Corno di Bassetto, made by Austin and voiced by David Broome in 1994, was added on a unit windchest during John Bishop’s time as curator. That left one windchest position free, hence the useful 4′ Fugara, midway between the Diapason and Viola. The surprise here has been the Orchestral Trumpet, of narrow scale with slender, bevel-ended shallots like those in an English Horn. The stop had been converted to 4′ in the 1960s and rebuilt several times. Now beautifully restored to 8′, and voiced with suppleness, the Trumpet falls midway between the Swell’s dark and bright reeds, lending keenness to the massed foundations.

SOLO: The Gambas and Concert Flute have been returned to a more extroverted state after some Faxon era taming; the color reeds are familiar and excellent. A splendid new Tuba Mirabilis, built by Shires, crowns the tutti. Added in 1987 and voiced by Jack Steinkampf, the copper horizontal trumpet had been revoiced in 1994 at Austin by Zoltan Zsitvay. For this project, its pressure was lowered to 10″ and voicing adjusted again. It is now more of a final chorus reed than a fanfare stop, properly leaving that role to the Mirabilis.

PEDAL: The original scheme has been largely reinstated, with a few tweaks. Foley-Baker’s adroit engineering and reconditioning of the 1921 open wood is a great success. While hardly Skinner’s largest scale, these pipes nevertheless prove the building amply supportive of low frequencies. Dr. Ferris’s 32′ Bourdon may have improved on Roosevelt’s, but it tended to cough and sputter. Higher cutups did the trick here, improving speech, power, and fundamental. The 1929 Pedal Trombone is another winner from Skinner’s best period. Try as we might, however, we could not persuade Washington Cathedral to relinquish Trinity’s original 32′ Bombarde pipes. Therefore, A.R. Schopp’s is building its first true Skinner replica. Bernie Talty of Parsons Pipe Organ Builders joined Jonathan Ortloff and me for a day at Kilbourn Hall in Rochester, documenting Opus 325’s 32′ Bombarde in detail. David Schopp and his team have done their own research at Opus 582, in Stambaugh Auditorium, Youngstown, Ohio, studying Skinner’s method for mitering wood pipes. This crowning element should arrive in 2020.

The Team

In this project, the Foley-Baker team, headed by Philip Carpenter, and I planned various details over several years. When contracts were signed in 2017, Foley-Baker took on the larger mechanical tasks and major chest modifications. Having installed the new Choir and Solo windchests in 2001, and partnering often with Organ Supply Industries since then, it was logical that Foley-Baker work with OSI on those tasks. Foley-Baker also handled reed re-racking, as well as coordinating re-mitering by pipe maker Tim Duchon. In Boston, my team handled flue pipe reconditioning and racking, most pipe removal, trucking, and installation, and all tonal finishing. The staff of Ortloff Organ Company (where I have shop space) gave material help with pipe reconditioning, while the Organ Clearing House served up their usual unflagging assistance as movers in chief.

Eastman-trained organist Duane Prill has been voicing organs for 30 years, chiefly at Parsons Pipe Organ Builders as well as with Manuel Rosales on several projects. In our work together over the past decade, Duane has been more than just a tonal finisher, but someone with musical and technical insights that always enrich the result. In a similar vein, it’s hard to think of working on a Skinner-related project of this magnitude without reed specialists Christopher and Catherine Broome. Apart from the 32′ Bombarde, every reed pipe here has gone through Chris’s hands; the beauty, variety, and stability of tone is indelibly linked to his talents. Last, but hardly least, my primary work colleague, Joe Sloane, has made all manner of things possible: racking new flue pipes, repairing toeboards and chests, managing crews, getting chambers clean again after 20 years of Copley Square tourism and dust. Since 2008, Joe and I have jointly curated some of Boston’s landmark instruments, and nothing I do in that vein would be remotely possible without him.

Finally, this project would not have happened without the leadership and drive of the musicians: Richard Webster and, from 2011, Associate Director of Music Colin Lynch. These gentlemen have been engaged at every turn, in fundraising, congregational education, console design input, and tonal suggestions. But the best part has been their sheer enthusiasm. It’s easy to work on any project when the musicians are this encouraging, supportive, and patient.

* * * *

Would Ernest Skinner have recognized this mélange of original, relocated, and replicated material? We can’t know, of course, just as only time will tell whether this is something of permanence or merely another revolution of the carousel. The far richer and warmer sound seems, in the end, only marginally less brilliant than before, pervasive without being ponderous. Even at full bore, the ensemble stops shy of that point at which energy for its own sake devolves into mere loudness. There is still space for the voices this organ hopes to lead. And that, at least, is something Skinner clearly sought, even in his most powerful instruments. After all, in this commanding space, shouldn’t God and His faithful take center stage?

Jonathan Ambrosino is a tuner-technician based in Boston, who also works nationally as consultant, tonal finisher, and writer. His other work on 20th-century American organs includes the 1930 Aeolian at Longwood Gardens; the Skinners at St. Paul’s Rochester (1927) and All Saints, Ashmont (1929); the Aeolian-Skinners at Calvary, Memphis (1935), Groton School (1935), Church of the Advent, Boston (1936), St. Mark’s Philadelphia (1937); and the Kimball at St. John’s Cathedral, Denver (1938).

Photography: Len Levasseur